Adi Talwar

A late morning scene at one of the city’s Meal Hubs, P.S. 056 in the Bronx, on May 14th.The day after a woman who was homeless died of starvation in Grand Central Terminal 35 years ago, the Coalition for the Homeless started their food program, now the largest mobile soup kitchen in the country.

Every night, volunteers drive three vans around the city and provide food. Even during Hurricane Sandy and on the night of the September 11th attacks, they were there. Before the pandemic, Coalition for the Homeless would likely be serving 800 meals each night this time of year; because of the impact of COVID-19, they’ve had to increase that by 40 percent. Still, they are used to serving food during emergencies, according to executive director Dave Giffen, who says one of the core principles of their program is reliability.

“People have a lot of unpredictability and instability in their lives. Having no barriers to getting the food is critical,” he says.

Even before the COVID-19 public health crisis shut down New York City, 1.2 million residents were food-insecure. Last month, the mayor’s office estimated that number had risen to “somewhere between 1.9 million and 2.2 million since the pandemic struck, based on the volume of unemployment claims from low-income New Yorkers and estimates from undocumented residents,” Politico reported.

For its part in addressing the consequences of the virus on the economy and access to food, New York City had to dramatically change and expand its offerings. The city has faced several bumps along the way in getting meals delivered reliably, and having consistent information available for New Yorkers who need help obtaining food. Charles Platkin, of the Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center, says such challenges aren’t shocking, given the speed and massive scale required of the city’s response efforts.

“They are doing an incredible job now, but that job is not an A-plus,” says Platkin. “It’s a good job under the circumstances.”

Joel Berg, CEO of the advocacy group Hunger Free America, agrees, “They’ve done in a few weeks’ time what normally would take the government a few years to do. It really is a colossal accomplishment.”

But experts like Platkin and Berg emphasize that the city still needs to improve and expand the reach of its food and meal programs, especially as the pandemic and its economic impact lag on.

“They understand they need to do even more,” Bergs says.

A drastic increase in food insecurity

The city’s efforts to respond to intensifying food insecurity have evolved significantly since New York went on lockdown in mid-March. Shuttered school buildings were turned into Meal Hubs and initially provided to-go meals for students only but later expanded, offering meals for any New Yorker who showed up. Senior centers also initially offered grab-and-go meals for participants to pick up, before switching those seniors to a meal delivery program to minimize their exposure to the virus as it spread through the city.

“I think the city worked as well as can be expected [because of] what happened so incredibly quickly,” says Rachel Sherrow, associate executive director and chief program officer at Citymeals on Wheels, which provides weekend, holiday, and emergency meals to city seniors. “People were literally asked on a Friday to no longer go to their senior centers.”

In late March, de Blasio appointed Department of Sanitation Commissioner Kathryn Garcia as his new COVID-19 “Food Czar,” charged with overseeing the city’s approximately $170 million food response program, which includes its meal deliveries and Meal Hubs in school buildings, along with $25 million in funding for food pantries across the city, which have been struggling to keep up with increased demand.

In an interview on WNYC’s The Brian Lehrer Show earlier this month, Garcia said keeping New Yorkers fed during the crisis has been an “incredible endeavor” that’s required “an unbelievable effort across all agencies.”

“We have been climbing a very, very steep hill,” she said.

The city’s Emergency Food Home Delivery program has served more than 7 million meals since the start of the pandemic, according to a spokesperson. Those meals, delivered by taxi drivers the city recruited as part of its relief efforts, include 920,000 meals delivered to NYCHA facilities and 57,000 sent to seniors who’d previously received food from local senior centers.

The delivery program is open to New Yorkers who can’t go out to get food on their own during the pandemic, can’t afford to have groceries delivered, and who aren’t already receiving meal assistance from other providers. They’re able to order three days of food per delivery (nine meals per person, with households limited to no more than 18 meals per delivery). Participants can sign up through the city’s online portal or by calling 311. Local senior centers can also explain the process for enrolling in the meal delivery program to those who reach out to them.

Garcia said the city is still working to enroll more vulnerable residents in the program and expand its delivery offerings, typically pre-prepared meals mixed with fresh produce and some shelf-stable grocery items. She also mentioned that the city is looking to provide better and more culturally-competent food, which now includes halal, kosher, and pan-Asian options.

“We have added a lot more prepared meals that have more variety,” she told Brian Lehrer last week.

The city has also expanded the number of its school Meal Hubs, which are open Monday to Friday, from 7:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. There are now 475 Meal Hubs operating across the five boroughs which have served approximately 11 million meals so far, averaging about 485,000 a day, a city spokesman said. Vegetarian and halal options are available at all sites, while kosher meals are offered at more than a dozen specific locations. Visitors to the sites can take up to three meals at time for each person in their household.

Meal Hub staff members are professionally trained to prepare food in batches and to limit food waste, returning any reusable products back to inventory if unused, a DOE spokesman said.

‘Hiccups’ and disappointment

Despite improvements over the last several weeks, advocates have raised some concerns about both the city’s grab-and-go sites and its emergency food deliveries, especially when it comes to consistency and responding to needs of specific groups, like those with dietary restrictions.

Early on, the city was criticized for being slow to roll out Meal Hub sites with kosher options. There were other mishaps, like missed deliveries and incorrect meals that had big consequences for the seniors using the city’s meal delivery program.

“It hasn’t gone off without a hitch,” says Berg, though he added that many of those problems have since been ironed out. “I don’t want to overemphasize the hiccups. In general, people say, ‘Hey, we’ve gotten the food and it’s actually pretty good.’”

Challenges do persist. Keeping the large network of Meal Hubs open and properly staffed each weekday has been one, according to Liz Accles, executive director at Community Food Advocates, who says there’s been “a certain amount of openings and closings that happen throughout, because people are getting sick.”

The Department of Education did not answer queries about whether such closures have occurred and how often, or how many of its Meal Hub workers have gotten ill with COVID-19 so far. A department spokesman told City Limits in an email that some Hub locations “may be temporarily closed due to staffing changes or in response to shifting community needs.”

The DOE follows all local and federal guidelines for essential worker safety, the spokesman added, and all of its Meal Hub sites are cleaned nightly.

Advocates say more outreach is needed to make New Yorkers aware of the free meal options available to them, including better signage at the sites themselves. At P.S. 234 and I.S. 126 in Astoria, for instance, there was little to indicate that the schools were operating as Meal Hubs other than a few black-and-white fliers posted to buildings’ front doors. At P.S. 169 in Bayside, the sign out front makes no mention that the building is now a meal hub, and the path to the front door is too long for someone to be able to read a sign posted there from the sidewalk.

In a recent parent survey conducted by The Education Trust-New York, just 62 percent of New York City parents said yes when asked if their school was providing meals during the shutdown, causing advocates to worry that the remainder might not know about the Meal Hubs.

“Like anything, getting the information out takes time, persistence, and creativity,” says Accles.

Coming from his experience leading the Coalition for the Homeless, Giffen explains that particularly for the most vulnerable, including people who are homeless or lack access to internet service, consistency is crucial.

“There are thousands of people struggling for survival on the streets of New York City,” he says. “When you don’t know where you can sleep one night to the next, how are they going to access the information?”

Others involved in local anti-hunger efforts say they’ve been disappointed with the city’s meal efforts so far. Moumita Ahmed helped start the Queens Mutual Aid Network, a volunteer group that’s been working throughout the pandemic to supply food and groceries to the borough’s most vulnerable residents, including many Muslim families. Despite the city’s efforts to increase its halal meal options — including distributing 400,000 additional halal meals during Ramadan, which ends later this month — Ahmed says she and others who’ve accessed those meals found them “really inadequate.”

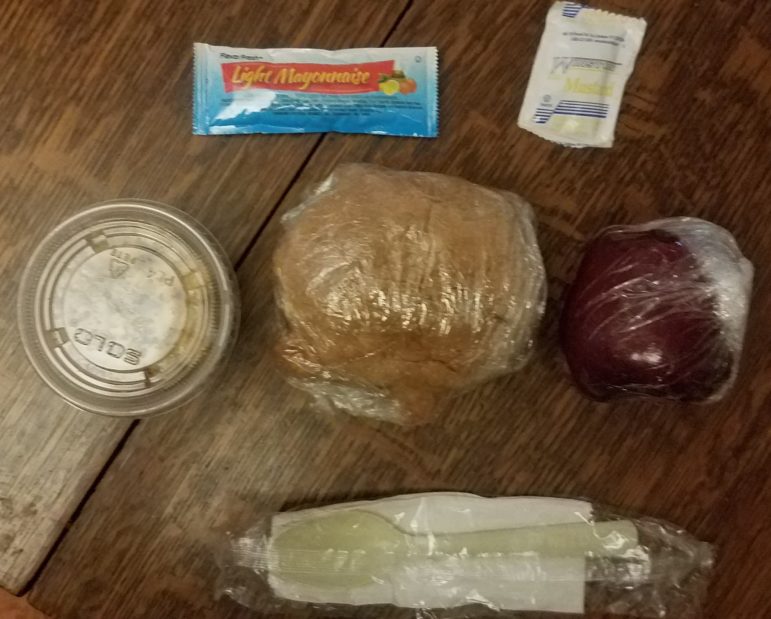

At some of the city’s Meal Hubs, those halal options have meant peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, she and others say, while one of the Ramadan meals offered via the city’s emergency food delivery program included an unappetizing, military ration-style pouch of chicken, beans and corn. Advocates Ahmed knows of places in other parts of the city, however, that have reported getting better quality meals from the city, raising questions about potential disparities.

“How are they distributing the meals? Who is making the decisions? How come certain organizations delivering food are distributing better food?” she asks.

In an email, DSNY Spokesman Joshua Goodman denied there are discrepancies between neighborhoods and locations. “There are sometimes differences day to day based on supply,” he said. “We provide a consistent quality of food citywide, and appreciate the opportunity to address any issue that may arise.”

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams also raised concerns about the quality and healthfulness of the food the city is providing, saying “We can’t address one crisis by perpetuating another.” In a statement to City Limits, Adams said, “We have been proud to support the City’s efforts to ensure no New Yorker goes hungry–but at the same time, we must ensure that the meals they’re receiving actually promote healthfulness.”

He continued, “The leading co-morbidities associated with COVID-19 are diet-related, such as diabetes and hypertension, and disproportionately impact communities of color and low-income areas. Instead of serving canned meat, we should be offering legumes. Instead of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, let’s serve healthy plant-based meals.”

Goodman says the city abides by strict nutritional guidelines for the food it distributes, especially for its senior meals. The city is “constantly reviewing and evaluating” the many food vendors taking part in their “enormous emergency feeding operation.” He told City Limits via email, “If someone is providing inadequate or inappropriate food, [they] will not remain a vendor.”

Murphy

… and lunch.Taking a cue from grassroots groups

When it comes to how New York City can improve its efforts on addressing hunger, advocates say the city should take a cue from grassroots groups. The Queens Mutual Aid Network and other groups say they would like to see the city partnering more directly with local restaurants, markets, and food vendors, both as a way to make more palatable and culturally-competent meals and to support small businesses that are struggling to stay open.

Shahana Hanif, a community organizer in Brooklyn, says that’s the approach she and other volunteers have taken, purchasing from local halal vendors, eateries, and supermarkets to create grocery packages for those in need. Some organizations have also set up halal food carts to dole out free meals of chicken and lamb over rice to feed New Yorkers during Ramadan.

“The city could mirror this,” Hanif says, instead of resorting to vendors and “cheap bulk products which are overly processed.”

“Many people might think, ‘What’s the big deal? This is a crisis moment, we’re lucky that we’re getting food in the first place.’ My answer to that is, okay. But in the same breath, we have to do better,” she says. “We have to just stop accepting good enough and demand better quality.”

New York City’s COVID-19 emergency food plan indicates that the city may be moving in that direction. The city’s report called restaurants “a critical part of our food system” and says that in the next phase of its efforts, the city “will integrate the restaurant industry into our efforts, building capacity for culturally-competent meal preparation in neighborhoods across the city for the duration of this crisis.” The plan points to private-sector food providers like World Central Kitchen and Rethink Food NYC as models.

Rethink Food NYC, which collects excess food from restaurants, shops, and commercial kitchens across New York and repurposes it as meals for those in need, has been ramping up efforts in response to the pandemic, according to co-founder Winston Chiu. They work with dozens of restaurants, providing them with funding so they can stay open to feed frontline workers and hungry residents during the crisis. They are hoping their program can eventually serve as a national model so that restaurants can be a part of relief efforts during future emergencies, rather than shutting down and facing economic distress of their own.

Chiu says their model includes frequently canvassing the communities and residents they serve to improve their offerings, creating “culturally specific meals” for different populations. He cited the example of older residents in Chinatown who received city-provided meals that “they don’t quite understand.”

“They were getting stuff like peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and they didn’t really know what it was,” he says. “I think the city’s doing it’s best, but one thing that we see is there is an inconsistency.”

Of course, private and nonprofit emergency food providers aren’t working on the same scale as the government. In addition to its fleet of taxi drivers delivering emergency meals, the city has kept its school food employees working to staff the city’s Meal Hubs. Even before the pandemic, the city’s schools were serving 900,000 meals across the five boroughs each day.

“No one can match the scale of government to respond in a crisis like this,” says Accles of Community Food Advocates. As the pandemic continues, she’d like to see the city’s Meal Hubs start incorporating more shelf-stable pantry items alongside its prepared meal offerings, especially on Fridays, so families can use those to help cover their needs over the weekend when the hubs are closed.

City Councilmember Helen Rosenthal, who represents Manhattan, says she would also like to see the city’s current programs refined to include more fresh produce in grab-and-go meals. She also wants better oversight of its emergency food delivery program, which has been rife with problems for the seniors in her district.

“To this day, we know of seniors who are getting multiple boxes and other seniors who are getting none,” she says, adding that she thinks the city needs to evolve the program from a stop-gap emergency measure into something more efficient and robust, especially as the crisis stretches on.

“I really understand it’s challenging, but on the other hand, I think we have an obligation to get it right,” Rosenthal says.

Help from Washington?

On a recent weekday, the grab-and-go offerings at two different Meal Hub sites in Astoria — P.S. 234 on 29th Street and I.S. 126 on 21st Street — included items like peanut butter and jelly, cheese and turkey sandwiches, hummus and chips, graham crackers, and assorted pieces of fruit.

Aside from a front door propped open, there weren’t many signs of activity outside P.S. 234. Inside, take-out meals were set up on tables for visitors to grab. The school food workers and security guards who staff the building stood inside behind another set of doors, but were visible through windows so that visitors wouldn’t have to interact with them face-to-face. Around 8:30 a.m., a handful of visitors had lined up at the site, all of them wearing masks about six feet apart from each other.

One visitor, Tony Maarouf, lives nearby and had heard about the Meal Hubs from his children. Since the coronavirus crisis struck, his hours working as a concierge were cut down to just two days a week, making it difficult for him to make rent while taking care of his three children at home.

“It’s a little bit hard,” he told a reporter as he exited the Meal Hub site, where he’d picked up breakfast packages that contained items like milk, fruit and cereal. He said he was grateful for the food, and for the stack of face masks he was able to pick up.

“So far, so good,” he said.

New York’s meal relief initiatives are dependent in part on federal funding from Washington, which has been limited and slow to arrive. Some relief has come through, including the recent approval of Pandemic EBT, which will provide extra food assistance funds for families with children enrolled in the free or reduced-lunch program (which applies to all of the city’s public school students).

Anti-hunger advocates are also pushing for Congress to pass House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s “Heroes Act” — a next-step coronavirus relief package that would extend the length of time those EBT benefits are provided, expand benefits for SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) recipients and increase funding for WIC nutrition programs. On Friday evening, the House passed the Heroes Act, but it’s unlikely the bill will make it through the Senate with all its provisions intact.

“The federal government has a significant responsibility to make sure that … localities responding on the front lines are supported financially and are not spiraling,” Accles says. “On the city level, we hope the response and the level of response continues to calibrate to the need over time.”

Similarly, Platkin hopes that once the city begins to recover from the impact of the coronavirus, the most vulnerable groups aren’t left behind.

“My worry is, what happens as everything recedes?”