NYS DOH

A page from the state’s official breakdown of nursing home death tolls. Gurwin says its COVID-19 count (at press time) is actually 37.Earlier this month, employees of a top-rated Long Island nursing home said they began seeing some of the facility’s more vulnerable residents suddenly growing sick. Several patients with dementia—already needing extensive, round the clock care—suddenly came down with high fevers. Most of them would develop pneumonia and eventually need oxygen. Then, they started dying.

“We had six people die in just three days. It’s catastrophic,” said a nurse in the ‘memory care’ unit on April 13th. “Some of them were like family to us. They even knew my kids.”

The nurse at Gurwin Jewish Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Commack, asked to remain nameless out of fear of retribution.

By April 23rd, at least nine in the locked, isolated 60-bed memory care ward, all of whom had severe and debilitating dementia, had passed away from COVID, according to a spokesperson for Gurwin. (In a later exchange, Gurwin representatives declined to confirm the death toll for any specific units, citing patient privacy.)

But it wasn’t just memory care—people in other parts of the 460-bed facility were getting sick and dying, too. All in all, by May 1st, Gurwin Jewish–whose rehabilitation, adult day care, health aides, and assisted living services won the 2019 Best of Long Island award–had lost 37 residents to COVID-19.

In order to increase their morgue’s capacity, workers began using an on-site trailer.

“I have never seen anything like it,” the memory care nurse said on April 22nd. “I can’t even cry anymore.”

Staff members were getting sick, too. People were in and out of work, developing high fevers, and testing positive for COVID-19. According to Gurwin’s CEO, one housekeeper even died from the disease. Despite constant reshuffling of personnel to fill the gaps, the 460-bed facility was so short staffed that they had people working overtime, sometimes back-to-back shifts. Some staff members, including the memory care nurse, say that despite repeatedly requesting more personal protective equipment they were told to start reusing N-95 masks–a practice that lasted for up to two weeks.

Tracking the spread

As is the case for many nursing homes, the breadth and depth of the pandemic’s impact on Gurwin Jewish is hard to gauge. Gurwin spokespeople say they couldn’t comment on the number of “presumed positive” cases–untested, often symptomatic people who may have been exposed to staff or residents with COVID-19.

The nurse and a certified nurse assistant, who also asked not to be named, both said that many people with COVID-like symptoms weren’t being tested, and as a result the disease was spreading faster than the administration realized.

But Gurwin’s CEO Stuart Almer says that the facility, which recently went through two rounds of Medicaid cuts, is in better shape than many. According to Almer, they had been preparing for the pandemic for weeks, imposing a strict no-visitation policy by mid March and trying to acquire sufficient personal protective equipment. When the state failed to provide them with PPE, they went out and bought their own.

“We got out in front and we’ve been aggressive with our buying through many sources. We’ve been okay, we’ve never been short of anything,” Almer said.

“Could we use more gowns quickly? Yes.” He added.

The governor’s mandate

As the crisis worsened nationwide, adult care facilities in New York were faced with a major new challenge: Beginning on March 25th, Governor Andrew Cuomo issued a statement requiring nursing homes in New York to admit COVID positive patients who had been hospitalized and released. This concerned Almer, whose own father is a resident of Gurwin.

“There was a mandate weeks back that required us to take COVID-19 positive patients,” Almer said, “and that was a very troublesome decision without planning. It’s just dangerous for any of us who are running nursing homes.”

Nursing homes across the state began taking in recovering patients. Problems already facing nursing homes throughout the country–maintaining adequate levels of personal protective equipment, isolating COVID positive patients, tracking the spread of the disease among staff and residents, and protecting everyone –only got worse. But Gurwin tried to take it in stride. According to their website:

“In response, we’ve created a designated unit at Gurwin in a closed, isolated portion of 2 North for recovering COVID-19 patients who are ready for discharge from the hospital. This unit is accessible via a separate entrance in the back of the building that does not require passing through any other resident care area. The unit staff is dedicated to this newly designated unit and includes nursing, rehabilitation and housekeeping personnel who are outfitted and have been trained in the use of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). Infection prevention measures have been taken throughout the entire facility – staff is wearing masks at all times when in the vicinity of residents.”

Prior to the mandate, Gurwin had one person who had tested positive. Then, according to Almer, they took on 23 COVID positive patients from nearby hospitals. According to Gurwin, by April 29th they had 80 confirmed COVID positive residents: 40 in a dedicated COVID positive unit and the rest in other parts of the facility. As of May 1, the facility had over 150 documented cases overall, including 38 recoveries.

‘Floating’ staff members

“Positive cases can arise elsewhere,” Almer said, meaning outside the dedicated COVID unit. “But when they do we put very specific protocols in place. So for example, you know, we limit staff so that if they’re dealing with positive residents, they’re only dealing with positive residents.”

But despite efforts to keep COVID and non- COVID staff and residents isolated, two workers said that it wasn’t always possible.

“We’ve been so short staffed…I know for a fact that people have had to work in COVID and non-COVID wards,” the memory care nurse said.

“I work with people who have COVID and was sent to work on a floor that has no COVID patients,” said the certified nursing assistant, who confirmed that the shifts were back-to-back, on the same day.

In an email from April 23rd, a Gurwin spokesperson told City Limits that staff members are sometimes required to “float,” or work two shifts back to back in different parts of the facility, to maintain staffing levels. While it’s not their policy to have people float between units with different COVID status, another Gurwin spokesperson acknowledged that despite their best efforts to contain the spread, by April 28th there was only one unit at the facility that had no COVID positive or presumed positive cases.

Gurwin maintained that the facility always follows CDC and DOH guidelines for infection prevention–including those pertaining to personal protective equipment and testing. They acknowledged that N95s are reused per the new CDC guidelines, which Almer says were put in place for facilities that couldn’t keep up with the unprecedented demand for PPE.

Questions about testing

Almer also says Gurwin is following CDC guidelines for testing. As of March 21, CDC guidance long-term care facilities and nursing homes states that “testing of residents with suspect COVID-19 is no longer necessary, and should not delay additional infection control actions.”

“We have testing kits but whether we use them or not, we’re just treating it the same because we know how to recognize symptoms,” said Almer. “We’re not required to just test all patients in the building,” he continued, “So we’ve been testing as need be. But testing may not change anything if we’re already treating a unit that has residents with symptoms [who] may not have anything to gain by testing.”

But the two staff members at Gurwin who spoke to City Limits fear that the lack of testing could put everyone in the facility at risk.

According to a Gurwin spokesperson, to be safe the administration considers anyone with symptoms to be presumed positive. But with staff floating between wards, reusing PPE, and an alarming number of staff and residents showing telltale symptoms of COVID-19, the spread of the disease has proven difficult to track and contain.

When asked how many residents were presumed positive, Gurwin spokespeople didn’t know. They also did not provide an estimate for the number of infected staff members, though Almer acknowledged that all staff members are screened for symptoms and fever before every shift.

According to both the CNA and the nurse, at least eight memory care staff members missed work because they either tested or were presumed positive–but nobody really knows how many people actually contracted the illness.

“We’ve definitely been exposed,” the memory care nurse said, referring to the other staff working on her floor. “I don’t have any symptoms, but I bet if I was to get tested now I would be positive.”

Nursing homes: New epicenter of the epicenter

This type of uncertainty is not unique to Gurwin. Infectious disease experts cite the lack of availability of testing on a national scale, and the subsequent protocol implemented by the CDC as confounding factors when it comes to determining the real numbers.

And due to the disease’s insidious, asymptomatic spread, even nursing homes that prepared for months, like Gurwin, have seen significant losses.Two weeks ago, health officials began counting presumed positives among the deaths—which added 5,295 people to the count in New York City alone. Since then, data from nursing homes across the country has continued to emerge, helping the public understand the scope and scale of the pandemic’s effect on our country’s most vulnerable citizens.

According to data released earlier this month by New York State health officials, the coronavirus has killed more than 3,000 people living in assisted living facilities and nursing homes in New York—about 25 percent of all virus-related deaths statewide, and over 30 percent of all nursing home deaths in the country. The study, which was broken up by county, shows that nursing and adult care facilities in Long Island’s Nassau and Suffolk Counties have the state’s fourth and fifth highest death tolls. At 432 and 426 respectively, they were behind only Queens, Kings and Bronx Counties. However, those numbers are changing almost daily.

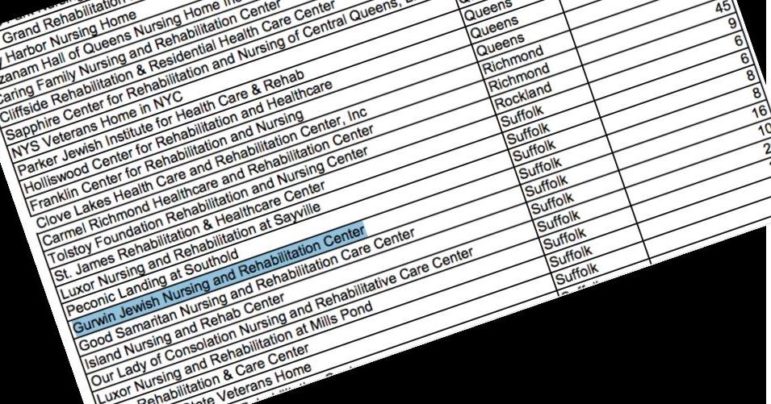

More specific data released on April 18th by the Department of Health revealed the names of nursing homes who reported five or more COVID-related deaths–and the number of casualties attributed to each. Gurwin Jewish barely made the list. As of May 1, Gurwin was listed as having eight fatalities, up from six when the list was first released April 12.

Almer says he prides himself on Gurwin’s transparency. He says the DOH must be using old data; according to Gurwin’s internal count, the 460-bed Suffolk County facility recorded 37 deaths as of Friday, May 1. While a spokesperson stated that the number 37 included only those who had tested positive–there were no other presumed positive deaths–in an email Gurwin told City Limits that the number is a combination of tested positives and presumed positives, and that they didn’t have a breakdown.

Neither Almer nor other spokespeople could account for the discrepancy between their count and the DOH’s figure. Gurwin called the DOH figure disturbing, and an injustice to their staff risking their lives on the front lines. As of print time, the DOH did not return multiple calls and emails asking about the discrepancy.

A Gurwin spokesperson told City Limits that there had been nine deaths in the memory care unit, before a different spokesperson said, “Gurwin is not confirming any information from individual units in order to respect the privacy of those patients and their families.” The two nursing staff members contended that 17 people had died in the memory care unit, and that only one was tested for COVID. While the nursing home did disclose their COVID-19 toll, Gurwin wouldn’t provide the total number of people who have passed since the crisis began, citing privacy concerns.

Almer says Gurwin has weathered the crisis well.

“Try to imagine an organization like this,” said Almer. “We have almost 1,200 staff. We have two buildings, you know over 700 residents altogether. We have a Home Care Program. It’s very hard to keep everybody healthy.” He said he hasn’t seen his own father, who’s lived at Gurwin for a year and a half, since statewide visitation restrictions were implemented in March. “We’re doing a wonderful job in light of an extreme situation,” Almer added.

But the nurse from memory care says she’s worried about her residents and expressed concern about the lack of testing being done

“Most of my patients can’t talk, and what they say doesn’t make sense most of the time. Or it’s memories from years ago,” the memory care nurse said. “They can’t tell me their throat hurts or they have a headache. A lot of families lost their loved ones with no real answers.”

“We’re the only human contact they have and they’re not coming out of their rooms and their families can’t come and see them,” said the CNA. “I always try to have a smile on my face even though it breaks my heart. Just losing them to the virus is heartbreaking.”

3 thoughts on “A Nursing Home Had One COVID Case. Then Came the New, Infected Patients.”

One more thing I give the nurse and aide alot of credit for coming forward and telling the public what is really going on inside the facility

This is just the sort of honest and proper response that I consider as I search (at the worst possible time) for a place for my beloved aunt. Thank you for reporting on this and thank the leadership at Gurwin.

please do a story on other local nursing homes in the area besides gurwin. workers and patients are getting sick with covid and the nursing homes only care about their profits while the patients and health care workers suffer.