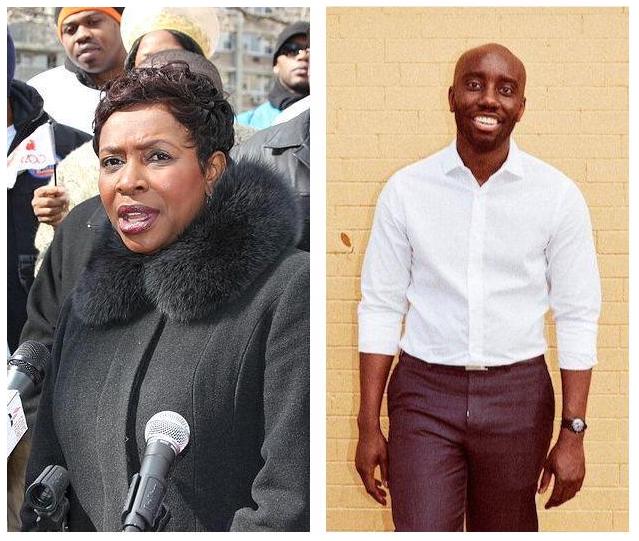

Office of Rep. Clarke/Bunkeddeko 2020

Rep. Yvette Clarke and Adem Bunkeddeko are two of the six declared candidates in the June Democratic primary for the Ninth Congressional district.The spotlight on housing issues is brighter in 2020 than in any election year in recent memory. Just about all of the top Democratic presidential candidates are pitching national housing plans. Mayor Bill de Blasio, who six years ago launched the largest housing-development initiative in the country, now says the city’s deepest housing needs still need addressing. With housing stress evident everywhere from the streets of L.A. to mobile home parks in Nebraska, housing might be the pocketbook issue that connects “red state” and “blue state” voters.

It could also be the defining issue in the race to represent New York’s Ninth Congressional district, which covers a chunk of Brooklyn running from Prospect Park and Crown Heights down to Sheepshead Bay.

Two years ago, rookie candidate Adem Bunkeddeko challenged Congresswoman Yvette Clarke and came within 1,852 votes of winning—equivalent to one half of one percent of voters in the district. The two will meet again in this June’s Democratic primary, in which the other declared candidates are Councilmember Chaim Deutsch, small business owner Lutchi Gayot, technology entrepreneur Alexander Hubbard and community organizer and Iraq/Afghanistan veteran Isiah James.

Bunkeddeko opened his second attempt to unseat Clarke with a length policy paper on housing that framed what he calls an “American Homes Guarantee” that would treat housing as a basic right.

In a more modest move, Clarke last year proposed a legislative fix to the way target incomes for “affordable housing” developments are set—a long-standing pet peeve of housing advocates in the city.

One thing that is likely is that housing affordability is a challenge facing many of those voters. About 70 percent of households in the district are renters. According to the American Community Survey, 53 percent of those renter households in the district pay more than 30 percent of their income in rent, up from 49 percent of renters in 2005.

The challenger’s plan

Bunkeddeko—who until recently worked for the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, a nonprofit that helps facilitate financing for housing and other development in low-income neighborhoods—says his “homes guarantee” would “ensure that every family can live in safe, accessible, and permanently affordable housing.”

His plan revolves around the construction of 12 million units of below-market housing through community land trusts operated by nonprofits or resident cooperatives.

Bunkeddeko also wants to build more senior and supportive housing. He says Washington should fork over the “$32 billion that the federal government owes NYCHA,” and he wants to clear legal barriers to the building of new public housing. Under the Homes Guarantee plan, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development would be empowered to investigate speculators and levy taxes on vacant property. He also backs an existing scheme that would create national rent control and a “right to counsel” for tenants facing eviction.

To boost homeownership in communities that “have been historically blocked from buying homes,” Bunkeddeko’s plan also calls for deeper down-payment support and the creation of a Community Opportunity to Purchase (COPA) program.

Put simply, the plan calls for creating a lot of housing, starting with the 12 million-unit target. By way of comparison, New York State and Ohio together host about 12 million housing units, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit has financed about 2 million homes since that mechanism was created in 1986 and there are 1.2 million public housing apartments in the country. Most estimates of the country’s housing shortage put it at about 7 million units, although that need will grow as population grows (the U.S. has 40 million more people now than it did in 2000).

“Given Washington’s devastating disinvestment in public housing, it is going to take a real commitment, well over $100 Billion a year for the next ten years or more to try to right this ship,” Bunkeddeko tells City Limits. “But we are past the point of this being optional; families in NYCHA are living in third-world conditions and homelessness is at its highest level since the Great Depression. It’s time for Congress to act.”

Bunkeddeko’s vision is more ambitious than even the most aggressive of the presidential candidates: Sen. Bernie Sanders has proposed building 10 million units and former Mayor Pete Buttigieg 9 million.

On one hand, that makes his plan unique. On the other, it means passing it would be a heavy left for a freshman member of Congress.

“It’s exciting that folks running for president, particularly Democrats, are talking about housing,” Bunkeddeko says. He believes his 2018 race, where housing was a focus, helped shape the conversation that the presidential contenders are now amplifying. “I believe there is a great deal of energy and work to put in if we are elected, because there is a lot of work to do.”

The record and the proposal

The race two years ago was easily the toughest Clarke had faced since 2006, when she won a four-way Democratic primary to succeed Major Owens, who’d held the seat for 24 years. The legendary Shirley Chisholm was Owens’ predecessor in the district.

In Clarke’s first term, spanning 2007 and 2008, she introduced the Real Estate Assessment Center Inspection Improvement Act and the Foreclosure Prevention Act of 2008. The following session, for 2009-2010, she reintroduced the Foreclosure Prevention Act and wrote the Affordable Housing and Community Development Act.

None of those proposals appear to have made it beyond committee, but they reflected some attempt to deal with housing worries. During the same time period, Clarke was somewhat visible as a voice on NYCHA, telling the Daily News in 2010: “I’m in Washington fighting . . . to get it right and make sure that New Yorkers of modest and low income can afford to stay in this place.”

More recently, however, Clarke’s attention—at least as a law-writer—moved elsewhere; her proposals tended to focus on terrorism, small businesses, immigration and other issues, although there was a 2014 bill to assist homeowners hit by disasters. Of the 235 press releases her office has issued over the past five years, only five were connected to housing.

It wasn’t until 2018 that she proposed another broad housing bill: the Hardest Hit Housing Act, which “would provide additional funds for various housing programs, including grants to large public housing agencies for specified capital activities, grants for foreclosure mitigation counseling and legal assistance, and incremental vouchers for rental assistance for large public housing agencies,” a Clarke spokeswoman says.

When she returned to Washington after the tough 2018 race, Clarke re-introduced that measure and two other proposed laws, the No Biometric Barriers to Housing Act and the Affordable Housing and Area Median Income Fairness Act.

Aiming at AMI

That last proposal attracted some attention last fall, because Area Median Income (AMI) has been a feature of almost every debate about affordable housing, rezoning and development in the city.

The federal tax credit and subsidy programs that underwrite most affordable housing peg eligibility to AMI. In New York City’s case, an odd legislative history means AMI is calculated on a region-wide basis, with Rockland and Westchester counties thrown in. Those skew the underlying numbers. Just as important, the feds adjust AMIs upward to account for high housing costs in the city. Taken together, it often means that “affordable housing” is priced out of reach of the families who need it most.

Clarke’s bill (which has 22 co-sponsors) would address both problems—and, importantly, appears to target the housing-cost adjustments only to how tax credits are used. That means her bill avoids lowering eligibility thresholds for Section 8 and public housing, which would exclude thousands of New Yorkers. The proposed law would also increase funding for affordable housing by $2.5 billion every year for a decade. A spokeswoman for Clarke says the bill “aims to cut rents in subsidized developments in the five boroughs by more than a third.”

While those aspects of the bill address key concerns, its overall impact could be complicated, since affordable housing is typically financed using multiple funding streams. Also, lower income levels serve needier people, but they also generate lower rent revenue to support housing developments over time. “Many programs are built around federal standards and fit together like a puzzle piece,” one housing expect told City Limits. “To truly understand the impact, there would need to be a thorough analysis of which programs would be impacted and how it might impact the cost of development.”

Bunkaddeko dismisses Clarke’s AMI bill. “It’s too little, too late and doesn’t address the issues at hand,” he says. “AMI is just a number or an index. The structural issue is that there isn’t enough affordable housing available here.”

Clarke’s office did not make the congresswoman available for an interview. In a statement, a Clarke spokeswoman said: “While Brooklyn’s economic make-up has shifted dramatically during Congresswoman’s Clarke’s time in office, she has been a relentless voice to ensure that Brooklyn remains affordable for everyday working families, including low-income communities.” New housing proposals are coming, the spokeswoman says.

Along with many in the New York delegation, Clarke is a co-sponsor of Velzaquez’s Public Housing Emergency Response Act, which would authorize $70 billion to shore up public housing around the country.

A race takes shape

On the campaign trail, Clarke maintains a lead in fundraising—she has $344,000 on hand compared with Bunkeddeko’s $189,000—but it is not clear if she will be able to achieve the financial advantage she had in 2018. Over the course of that cycle, Clarke spent $879,000 to Bunkeddeko’s $259,000, although not all of the congresswoman’s spending was concentrated on the primary campaign. (Clarke faced only token Republican opposition in the 2018 general election, winning with 87 percent of the vote.)

Deutsch’s campaign did not respond to multiple emails requesting comment on his own housing-policy plans. Gayot’s agenda highlights the potential of modular housing to help close the gap between supply and demand, and stresses the importance of transit infrastructure to making distant neighborhoods viable as housing hubs. Hubbard’s campaign website features the issue but offers few specifics.

James offers the most detailed plan to rival Bunkeddeko’s. It calls for taxes on non-primary homes, support for land trusts, federal backing for low- and middle-income housing cooperatives, and a crackdown on AirBnB, among other ideas.

3 thoughts on “In Election Rematch, Brooklyn Congressional Candidates Serve Up Housing Policy”

Representative Clarke clearly has the more realistic and achievable approaches plus the seniority to help passed needed legislation in the House of Representatives.

They may be more realistic and achievable, but the impact they’d have on overall housing affordability in Brooklyn is negligible. What’s needed is massive public investment in the bottom of the market.

There is need for a change Adam Bunkeddekko may be young/ new !! But has a great deal of fight in him for the people !!! I have gone to Congresswoman Clarke office for assistance when i was in jeopardy of losing my home and NOTHING was done !! Yvette Clarke surfaces when it is election time !! I receive automated phone calls, mail etc. As previously mentioned It is time for a change !!! She will not be receiving my vote !!! 👎👎👎