NPS, NYCHA, DVIDSHUB, Slowking

Clockwise from top left: Katadhin Woods and Waters National Monument, public housing in New York City, damage from Superstorm Sandy in New Jersey and a protest over the Dakota Access Pipeline in Washington, D.C.

Someday, if you are lucky, you will turn off Wyoming’s Highway 89 onto Antelope Flats Road, drive across a flat landscape of scrub brush and into a dusty parking lot, wander a few feet into the exquisite desolation of the National Park Service site called Mormon Row, and be utterly swallowed. The stillness there overcomes, unnerves. The beauty is vaguely terrifying: the vastness, the indifferent, primordial wind. The mountains to the east and to the west: Could you reach out and touch them, or walk for days and never feel perceptibly closer? It is hard to tell.

Two thousand miles away from Mormon Row, you can walk up Pleasant Avenue in East Harlem, where famed industrial designer Karim Rashid (a.k.a. The Prince of Plastic) has created a luxurious 20-unit condo building offering “bright and airy apartments” with “large private terraces” and a “common roof garden with stunning, panoramic views of Manhattan.” Studios there are renting for $2,200 a month. The building is just north of East 116th Street, the heart of Spanish Harlem, and just south of the 22-building Sen. Robert Wagner Houses, a public-housing complex where nearly 5,000 people live and $278 million in repairs are needed immediately. One in three people in East Harlem lives below the federal poverty level. A big chunk of the area was recently rezoned by Mayor Bill de Blasio to encourage more housing production, a move that sparked fears of gentrification and displacement—a threat embodied by luxury outposts like 329 Pleasant that seem to be transforming New York City, parcel by parcel, into a place working-class people cannot possibly afford.

Mormon Row, on the edge of Grand Teton National Park, up the road from the National Elk Refuge and a few miles south of the Bridger-Teton National Forest, sits in a state where nearly half the acreage is owned by the federal government. Wyoming is where local lawmakers and a federal judge have wrestled over whether it ought to be legal to hunt grizzly bears. It’s is the No. 1 state for gas production and No. 2 for oil extraction on federal land, with 1.4 trillion cubic feet of gas and 39 million barrels of oil generated off 8.4 million acres of federally managed territory in 2017—yet many of its politicians have clamored for more local control of public lands so they can be “used” better. In other words, Mormon Row lies in the middle of passionate debates about public lands in rural American, from the Grand Staircase Escalante and Bears Ears monuments in Utah that President Trump recently shrunk, to the Katahdin Woods and Waters monument in Maine, which dodged the bullet this time but faces critical tests.

329 Pleasant Avenue, meanwhile, exists in a city that has aimed an impressive array of conventional policy weapons at its housing affordability crisis, from requiring market-rate developers to build low-income units to providing lawyers to represent indigent tenants in housing court. Yet there’s little sign of the crisis easing, as hefty rent burdens persist and near-record homeless shelter counts remain. The fear of displacement in East Harlem mirrors worries around the country. In Denver, mobile-home residents are being uprooted. In Nashville, a mass transit plan sparked fears of displacement. In Buffalo, N.Y., grassroots activists are struggling to protect at least some working-class housing from the vagaries of the private market.

The housing crisis playing out in many U.S. cities and the intense debate about the control of rural public lands might not seem connected. After all, grizzly bears and (most) luxury developers have little in common; grazing rights and property-tax abatements are very different policy tools. In all these places, however, a renewed and vital debate is playing out over how to balance private motives and the public good, and especially the interests of working-class people, in decisions about the use of land.

There is no shortage of issues for Democrats running for president to talk about. But it will take something more than a collection of leftish policy positions to reach beyond loyal primary voters to the legions of decent people who understand that “Make America Great Again” is hollow and sinister but yearn for a cause with equal clarity.

Articulating a bold vision for the land—the urban and the wild parts of the United States’ great connective tissue and most finite resource—could offer a true alternative to everything Donald Trump represents, a message that resonates everywhere from Mormon Row to El Barrio.

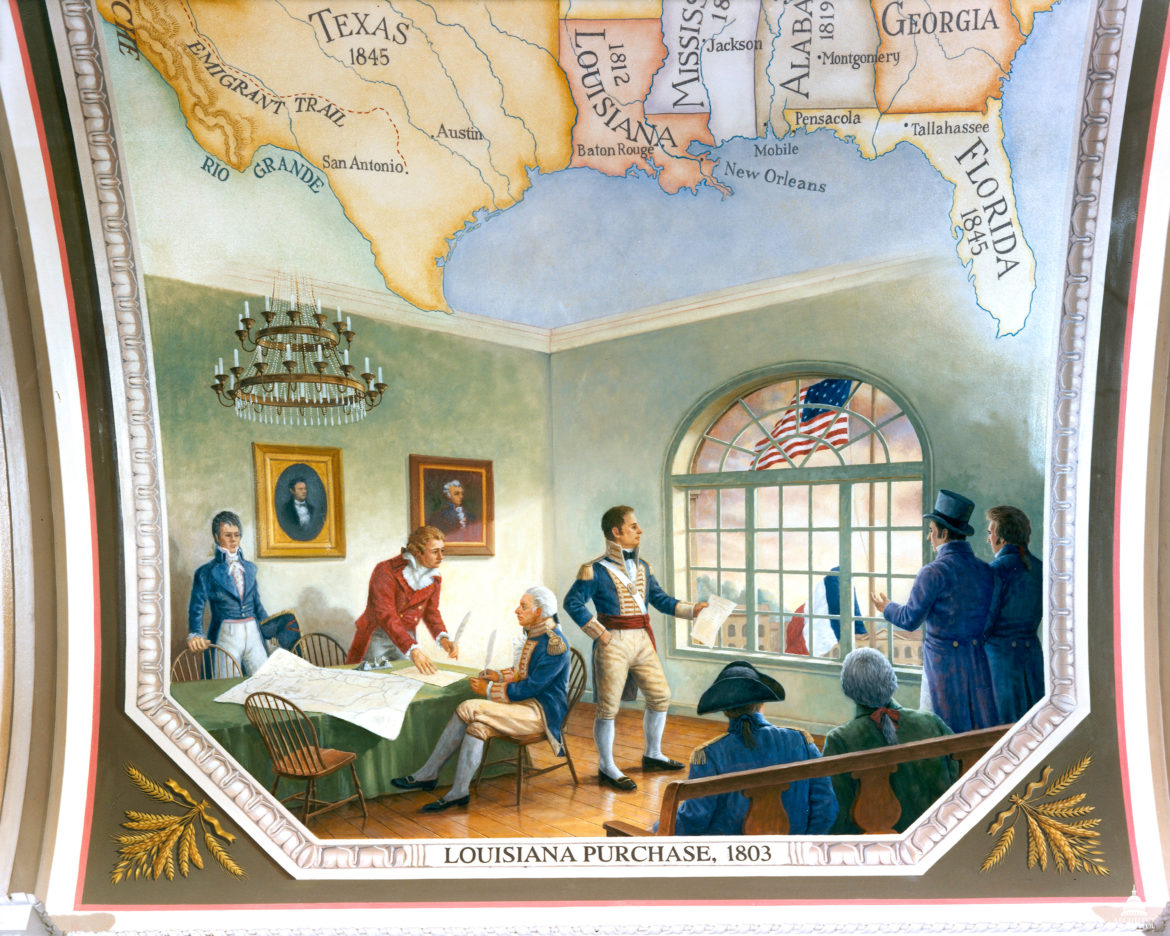

Architect of the Capitol

The Louisiana Purchase. Land deals like this weren’t just something the federal government did during the United States’ early years; they were a key rationale for the existence of a strong, federal authority.

Nowadays national politicians rarely spend much time discussing terra firma. But there was a time when land and property were all-consuming subjects of federal policy.

After achieving independence from Great Britain, there was a confused competition among the former colonies over the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. The need for some overarching authority to oversee that expanse helped make the case for a strong, national authority instead of the loose confederation that some early leaders preferred. It was that same, central federal government that bought the middle of the modern U.S. from France, conquered the southwest in the Mexican-American war, negotiated the Pacific Northwest away from the Brits, purchased Alaska from Russia and annexed Hawaii, all before the close of the 19th Century. Our gravest sins are inseparable from the land: the extermination of native people to ease access to new lands, the use of Black slaves to make land profitable.

Disputes over the geography of slavery helped trigger the Civil War. After the Confederacy’s surrender, radical Republicans advocated seizing rebel leaders’ land and distributing it to former slaves. That idea died, but under the Homestead Act and related policies the federal government did give away much the territory it had acquired during the nation’s expansion, eventually shedding two thirds of its holdings.

On the land over which Washington retained control, there were early steps toward a federal role in conservation in the late 1800s with the designation of Yellowstone and Yosemite as national parks. The role broadened with the creation of the National Park Service in 1916. It’s interesting that a federal interest in urban development and housing policy—an area where the feds at the time had no significant ownership role but presciently saw a policy stake—took shape around the same time, as the national government sponsored the creation of tens of thousands of units of housing for workers near the shipyards producing materiel to defeat the Kaiser.

It was the New Deal, however, that cemented a modern federal role in both rural land management and the housing market, especially urban housing. Bills like the Taylor Grazing Act that regulated ranchers’ use of public lands in the wake of the dust bowl and the Flood Control Act that led to federal measures to hold back rivers interjected federal policy into the relationship between the private market and natural resources. In a similar way, the creation of mortgage guarantees under the National Housing Act and the launch of federally-supported public housing through the Wagner-Steagall Act in 1937, among other measures, made the feds a player in the residential real-estate market, especially in cities.

Since then, in both the rural and urban arenas, the ideological pendulum of federal policy has swung wildly. Washington’s urban policy gave us public housing and redlining, then slum clearance and urban renewal, followed by the very brief War on Poverty, before the launch of Section 8 housing vouchers, the destruction of public housing under HOPE VI, and the short-lived Sustainable Communities Initiative under President Obama. Much of this history consists of social interventions—like public housing—that was knee-capped from the get-go by free-market ideologues and then held up by conservatives as examples of the failure of government.

Meanwhile, in our wilder places, federal land policy after the New Deal focused first on fostering extractive industries, then shifted in the 1970s to emphasize conservation and restoration. Almost as soon as the feds made that pivot to environmental protection, the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion broke out in several Western states, as local leaders demanded Washington relinquish control. By the 1990s, as Steven Davis points out in his book, “In Defense of Public Lands,” resistance to federal land policy took on darker tones as “sovereign citizen” movements preaching the gospel of “nullification”—and sometimes bearing arms—came into the picture. When the Tea Party arrived in Washington in large numbers after 2010, a slew of proposals to strip away protections for federal lands went into the legislative hopper.

The Republican message on land and the environment is easy to detest, but at least they are engaged enough in the topic to delve into a considerable level of detail. While the Democrat’s 2016 platform struck principled notes about agriculture and public lands, the language had the distinct tone of an afterthought.

The Democrats, for instance, offered a one-sentence vow in 2016 to defend the Endangered Species Act, while the GOP delivered a detailed argument for why the Act has “stunted economic development, halted the construction of projects, burdened landowners, and has been used to pursue policy goals inconsistent with the [law] — all with little to no success in the actual recovery of species.” The Democrats never mention the Bureau of Land Management; the Republicans point to alleged BLM restrictions on the use of public lands for oil and gas, as they vow to expedite “the permitting process for mineral production on public lands.” The Republicans mock the “Waters of the United States” rule and imply that the Forest Service is responsible for the increasing intensity of wildfires. These are not topics the Dems delve into.

The problem isn’t so much that the Democrats don’t answer the GOP point by point; rather, it’s that the Democrats don’t flesh out a rival vision for rural and public lands. And even when the party’s official agenda does offer a compelling alternative, like its vow to “phase down extraction of fossil fuels from our public lands … while making our public lands and waters engines of the clean energy economy and creating jobs across the country,” this was hardly a policy the Democrats spent any time or effort promoting.

“I’m not exactly sure what’s driving that” disparity between the parties, says Davis, a professor at Edgewood College in Madison, Wis. “It might be nothing more complicated than the urban-rural divide of the two parties’ bases. Western voters are heavily Republican and that’s a very big issue to them.”

Today the federal government claims about 640 million acres—25 million less than in 1990—a combination of national parks, national forests, fish and wildlife refuges, public lands under the management of BLM and military installations. Most of it is in the West. Just under 80 percent of Nevada, for instance, is federally controlled. About 0.3 percent of Connecticut is.

Yet of the 10 states with the largest federal land presence, California and Oregon are reliably blue. Colorado, Nevada and New Mexico voted against John Kerry but for Barack Obama twice and for Hillary Clinton. Arizona could be shifting too: Trump beat Clinton by only 3.5 percent there in 2016.

Admittedly, the other four big federal-lands states (Alaska, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming) are Republican strongholds that last voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in 1964. But that just means Democrats have almost nothing to lose there. Who knows how many votes might shift blue just by the Democrats demonstrating they really gave a damn about what those lands might offer the people who live near them? Maybe enough to force Republicans to devote a little money to protecting their big, red backyard?

Yes, Democrats can win the White House without coming within a country mile of winning one of those states. But can they govern well without trying to?

Terabass

A homeless man in Los Angeles, 2009.

When it comes to urban issues, the coin flips: Democrats are far more fluent and have more to say on topics like infrastructure spending, tax credits for urban entrepreneurs and homelessness than the GOP. But on the fundamental issue of housing, Democratic policies hew to the vague and the conventional, when an acute and unconventional crisis is what we face.

According to a 2018 report by the Pew Charitable Trust, from 2001 to 2015, the share of renter households nationwide that could be considered “rent burdened”—meaning they pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent—rose 19 percent, to 38 percent. The share of renters facing “severe” burdens (rent that eats up 50 percent of their income or more) shot up 42 percent. Data from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University show housing costs soaring for renters and homeowners alike: Median rents rose 20 percent faster than inflation from 1990 to 2016, and median home prices rose 41 percent faster than inflation. What’s more, the Center notes, “Despite their growing numbers, only about one in four very low-income renters benefited from subsidies to close the gap between market rents and what they could afford to pay” while “Homeownership rates among young adults today are even lower than in 1988, and the share of cost-burdened renters is significantly higher.”

While the housing crisis is not purely an urban phenomenon, it manifests itself in starkly visible ways in cities like Los Angeles, New Orleans and Seattle in the form of growing homelessness, embodied in tent cities under freeways. Those optics are often just the tip of the iceberg. The vast majority of homeless New Yorkers live not in plain view on city streets but out of sight in an elaborate and enormously expensive shelter system. And even those who are housed face housing risks. After years of federal disinvestment, public housing in New York City—which houses more people than live in Cleveland or St. Louis—needs $32 billion in capital repairs. One tool that New York and many other cities are using to address their dilapidated public housing is called Rental Assistance Demonstration. It puts public-housing properties in the hands of public-private consortia that can borrow money to make repairs—an innovative approach, but one that is untested and faces questions over what happens if the properties go into foreclosure.

Elsewhere in the country, the urban housing crisis shows a different face. The Denver Meadows Mobile Home Park in Aurora, Colo., is set to close at the end of May, uprooting dozens of families, after a private developer who bought the land refused an offer of $26 million from non-profit entities who wanted to preserve the moderate-income housing there. (Don’t let the “mobile” bit fool you: Although their occupants own them, some of the homes are so old they can’t be moved). In Portland, Ore., which has lost 25 percent of its Black population since 1990, a recent city-sponsored report found that 34,000 households are at risk of displacement as development continues along major transit corridors. Last May, voters in Nashville rejected a $5 billion transit plan emphasizing light-rail, in part because proponents never really addressed concerns among low-income advocates and the Black community that the corridor would trigger housing displacement.

And it’s not just in big cities where the housing crunch is creating worries. Community activists in Lynn, Mass., an unglamorous blue-collar suburb of Boston (Full disclosure: It’s my dad’s hometown and I lived there until I was 6) have raised alarms about plans for a mixed-use development on a 300-acre former industrial site where, the city’s consultants claim, affordable housing is not feasible. And in Buffalo, N.Y., a revival of the once deeply bruised downtown has activists worried about displacement. “Paradoxically,” writes the city’s Partnership for Public Good, “Buffalo has both a crisis of abandoned housing and a severe homelessness problem.” Even Jackson, Wyo., has a housing crunch.

These concerns are vastly different from the urban issues—crime, drugs and AIDS—that we talked about a generation ago. While still pressing in many cities, those issues have been overshadowed by the fundamental question of whether U.S. cities will be able to house moderate- and low-income people, and if not, where those families are supposed to go. The fact that this pressure is building in cities big and small across the country creates an opportunity and obligation for federal action.

CASA

Members of the Bronx Coalition for a Community Vision protest a rezoning of their neighborhood that they feared would lead to displacement of low-income tenants.

Clearly, progressive candidates need to support the tried-and-true elements of a rational housing policy, like fully funding a federal National Housing Trust Fund to build more income-targeted housing, and backing existing HUD and USDA programs that underwrite affordable housing. Approaches championed by the Obama administration—like the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing assessment to reduce housing segregation and the Sustainable Communities Initiative that linked federal housing, transit and environmental spending—are worth revisiting and improving.

But simply throwing more public money into the private housing market is unlikely to fundamentally reset the equation facing low-income urban families. That’s why in Buffalo, Boston, Detroit, New York and many other cities, housing advocates are developing or operating community land trusts, which offer permanent affordability and community control of the land in which government invests housing subsidies. These trusts acquire land and create or preserve affordable housing on it but, rather than giving the deed to a private owner who merely agrees to maintain some level of affordability for some time, the land is controlled in perpetuity by a community trust dedicated to permanent affordable housing.

In New York, their appeal has grown as regulatory contracts for affordable housing built or preserved in the 1970s and 1980s have expired, forcing the city to spend more to keep subsidized housing from going onto the private market. Athena Bernkopf is leading the effort to create a community land trust in East Harlem, and says says federal policy could play a role in scaling land trusts to be a significant defense mechanism for renters across the country. “We need communities to be given direct access to resources so they can take action on areas that they prioritize as need,” Bernkopf says, adding that existing federal subsidy programs need reform. Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, for instance, are reserved for projects housing people who make 60 percent of the Area Median Income, a measure that can be heavily distorted by polarized incomes in a given region. “Who are they really for, these subsidies?” Bernkopf asks. “Because it’s certainly not our community.”

Land trusts aren’t the only out-of-the-box solution that grassroots housing advocates are rallying around. There are also calls from groups like Right to the City and its Homes for All Campaign, for broader rent regulations and eviction controls, while others see a place for home-sharing initiatives for seniors and for a new era of “social housing” (like public housing, but with a range of possible ownership and income-mixing structures) modeled after successful European projects.

Tradition dictates that housing issues are local concerns, but the fact is, past federal policy is deeply implicated in the problems faced by cities. The impact of redlining and slum clearance, along with the federal highways that tore up urban neighborhoods, are still felt in many urban centers. Transit funding, mortgage deductions, drug-war policies—the presence of federal policy in the urban housing market is undeniable. From the destruction of public housing to the trading of federal tax credits, under Democratic and Republican presidents alike, the federal approach has embraced the ideology of the private market. And it is clearly failing. As was the case in the Depression and after the Second World War, it is manifestly clear that, given the economic limitations even large urban areas face, only the federal government has the power and purse to save U.S. cities.

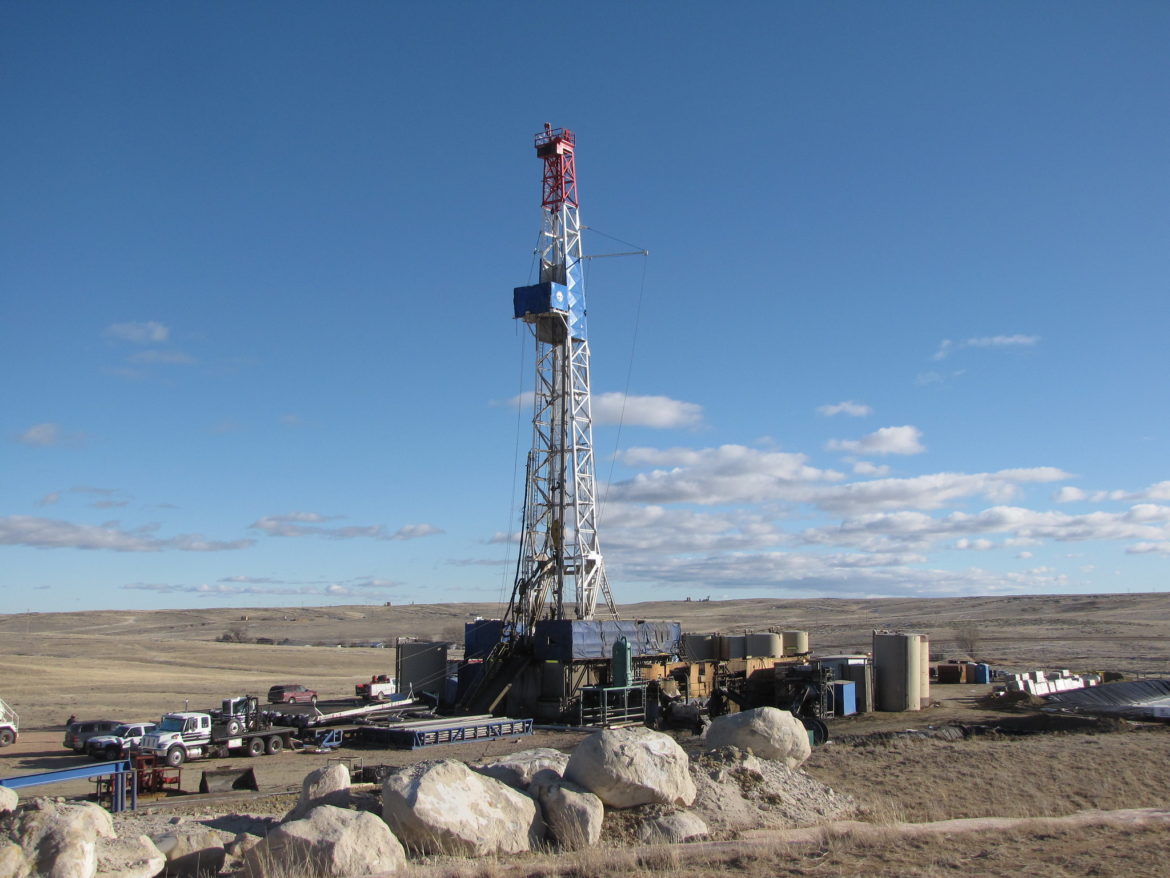

BLM

A drilling rig on federal land in Wyoming controlled by the Bureau of Land Management.

U.S. rural areas have their own housing issues. According to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition, 47 percent of rural renters are rent-burdened, and just under a quarter pay more than half their income toward rent. Problems like high housing costs, bad living conditions and overcrowding “are found throughout rural America, but are particularly pervasive among several geographic areas and populations, such as the Lower Mississippi Delta, the southern Black Belt, the colonias along the U.S.-Mexico border, Central Appalachia, and among farm workers and Native Americans,” NLIHC finds.

These issues cry out for federal attention—and maybe for a rural model of land trusts. But in non-urban American, housing is just one of the land issues that demands action.

In farming communities, the often convoluted ownership of farmland has been a major issue for the Rural Coalition, a 40-year-old national advocacy group for Black, Latino and Indian and low-income farmers and farmworkers. Divided ownership of farms for decades kept low-income farmers out of federal assistance programs. Recent federal legislation eased the problem, but implementation will be key. Beyond that, Rural Coalition executive director Lorette Picciano, federal policy has to recognize the role of farms as cultural assets and economic ladders. “We would like [candidates] to talk about land and … to remember that agriculture also is about building communities, feeding communities, and it’s also about taking care of the land and the climate. If we’re going to protect the climate, we need to keep the culture alive,” she said. “We’d like to have people that recognize how rural communities are connected to urban communities. We want to talk about caring to the land not in a mechanistic way – in a rooted way.”

The way farm ownership affects how people access farm assistance programs exemplifies the fact that there’s no immovable bright line between public and private interests in the land. This is true also of the federal role in regulating the kind of private-sector projects that occur on lands that aren’t government owned, like the Dakota Access Pipeline Project that passed through the water supply of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota, or the Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline that cut through Pennsylvania land owned by an order of Catholic nuns who tried to stop the project. Neither of those projects, nor their counterparts elsewhere, could have occurred without federal approval. After 2020, new national leadership could make a huge difference by changing how the federal government exercises its authority to regulate land use via the Clean Water Act, its highway authority, energy policy, flood insurance and more. These tools can all be harnessed to a vision that sees a broader public purpose to the use of all U.S. land.

On the land that’s actually owned by the federal government, the ongoing push by the Republican right to have Washington surrender control of much of its territory to the states has to be thwarted. But the status quo is not enough. The biggest holder of federal land, BLM, often betrays the trust it’s been given over irreplaceable resources. The Western Environmental Law Center in 2016 launched a court battle against BLM over an Obama-era decision to, with little thought to alternatives or environmental impacts, open up 10 billion tons of coal and permit as many as 18,000 oil and gas wells in the federally controlled Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana. The environmentalists won that round in 2018 (and a separate fight over fracking earlier this year) but disputes like that aren’t going to disappear.

As BLM has stealthily sold off access to public resources, right-wingers have made a loud push to shrivel the federal wilderness—the areas controlled by the Forest Service, Park Service and Fish & Wildlife Service. When Trump in 2017 decided to shave territory off the Bears Ears and Escalante holdings, he declined to act against 25 other monuments that were part of the same review. But that broader threat could certainly be revived if the politics of the moment called for it.

One of the areas that was on Trump’s initial hit list was the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, created by Obama in the final year of his presidency. Andrew Bossie, the executive director of Friends of Katahdin Woods and Waters, says the facility still faces local opponents. Among them are the people who long used the area for recreation. “There were a lot of concerns that creation of the monument would change in particular, snowmobiling, ATVing, hunting—particularly bear baiting and trapping,” Bossies says. “And it has. It has changed some of that.” ATVs are not allowed on the monument. Hunting is allowed in some places but not others. “That’s a big change,” Bossie stresses. Other opponents are upset about the loss of former logging land because they hoped it might once again support logging jobs.

Outsiders could dismiss those concerns. Or they could acknowledge there’s a community with deep connections to Katahdin land that is feeling the impact, on their hobbies and their dreams, of a federal presence. And it’s not benign. To turn those skeptics into stewards, Katahdin Woods has to provide benefits to its neighbors. “This monument was sold on an economic argument. While there’s still opportunity out here, what I’m hearing is, ‘I want to see results.’ We need to make it so people can make a living there and can stay there,” Bossie contends. “If we can create something that is special that is something people want to come to. That is a way to deal with the changing economic factors.”

So far, the economic boost is limited, Bossie says. Maybe that’s because the feds are only paying one permanent, full-time staffer for the entire Katahdin monument—all 87,000 acres, an area bigger than Philadelphia. Without more federal investment, it’s hard to see how a tourist infrastructure is supposed to grow. If the Democrats are, as they said in their 2016 platform, “committed to doubling the size of the outdoor economy, creating nearly hundreds of billions of dollars in new economic activity and millions of new jobs,” now might be a good time to say how.

Thomas Good

Damage from Hurricane Sandy in Staten Island.

Land issues can seem abstract in a political environment where a border “emergency,” allegations of Russian collusion and the debate over healthcare are what generate heat. Yet the control and use of land is embedded in many of our headline policy battles. Land access is a factor in the economic desperation that has driven tens of thousands of Central Americans north in recent years. If income inequality bothers you, then land inequality should, too: From 2007 to 2017, the territory held by the 100 largest private land owners in the U.S. swelled from 27 million acres to 40 million acres. Mounting research links housing quality to public health, and the connection between home stability and schooling is clear: The tens of thousands of students in New York City public schools who experience homelessness face steep challenges staying on grade level.

The biggest threat the U.S. faces, climate change, will be manifested significantly through the loss of land—in particular, coastal land on which millions of people live. These changes could necessitate once unthinkable decisions. “We’re going to have to take a long hard look at our settlement patterns generally,” says Eric Freyfogle, a professor at the University of Illinois College of Law and author who has written extensively about the culture of property in the U.S. He foresees nothing short of “the resettlement of America.”

That’s going to mean confronting tough questions about local control versus national priorities, and about how private-property rights—which, though treated as timeless and sacrosanct have been evolving since they were created—might need to evolve more to intersect with new and pressing public interests. Not easy topics. Hence the wisdom of articulating a progressive, inclusive vision for the land now—before the emergency.

Key to that vision is a bold vow to defend and expand the public sphere. At a minimum that means keeping federal lands intact and shoring up—rather than selling off—public housing in the city. But it would also mean creating new common lands, through active federal support for land trusts and new social housing. It means using federal policy tools like environmental approvals to protect natural resources for the broadest public benefit, even on privately held land, and making sure eminent domain is used for true public interests.

Nearly as important is investing, heavily, in making the public land—urban and rural—fulfill its fullest public purpose. That means much bigger staffs and better visitor facilities on all our wild lands, and deep subsidies for affordable housing on land trusts.

We also have to respect the fact that many thousands of working-class people make their living off the land in a way that—through no fault of their own—is not going to be viable much longer, and we must prioritize efforts to create new work that offers a different way of living in connection with the earth.

In addition, the voices of those impacted by these land policies, whether they are urban renters or homeowners or rural workers or ranchers, have to have a formal role in shaping the way programs are implemented; this already occurs for some federal territories in the form of “user groups.” That must happen more broadly.

Finally, we must be committed to a practical, scientific approach that aims to protect the health of all land resources while affording maximum public benefit and access. This is not about imposing a storybook version of the country or the city on a complex, modern reality. On public lands there are forms of resource extraction that might be safe, like species that can be hunted in a limited fashion. There are urban areas where the trade-off between housing and open space will be delicate, especially as sea-level rise creates the need for buffer land. (Indeed, when we talk about “land,” we’re really talking about the waters as well—our rivers, lakes, creeks and coasts.)

The most important part of the agenda, frankly, is to have one—and to invest some political capital in selling it. Otherwise, low-incomes tenants will smell an empty promise and Western workers will detect yet another elitist mandate from Washington with nothing in it for them. Even the spotted owl will sense that this is nothing but noise.

Stewart Baird

Mormon Row

What’s promising is that even in our polarized political environment, disparate factions have found common cause around issues of the land. In cities, voices on the left and the right have denounced subsidies for luxury development. In protests against the pipelines, trans activists have marched alongside elderly nuns. And recently, a broad coalition including environmentalists and ranchers recently came together to defeat a House Republican bill that would have forced the feds to sell off 3.3 million acres of public lands. The Western Landowners Association was against it, as was the Sierra Club, and they weren’t the only strange bedfellows. “The position we’ve taken here is we think the ownership needs to stay with the federal government. We definitely see some risk of transferring a lot of that ownership to the states,” says Blake Henning, chief conservation officer at the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, a hunter’s group based in Montana. “They’re more likely to sell it to private entities.”

The point is, a progressive vision for land could find a broad set of at least occasional, if sometimes very awkward, allies. Forging these partnerships will require hard work and smart choices, especially on the left. There are going to be future land issues on which hunters—often a voice for conserving wilderness—and gun-phobic environmentalists could find common cause. And if hunting is what gives tens of thousands of Americans a stake in the land, and a reason to fight for it, it is something we tree huggers must support. In the urban arena, there will be times when community land trusts, in order to create long-term sustainability, have to contemplate commercial development that doesn’t include beloved mom-and-pop operations.

Progressives will have to decide where absolutism is essential and where accommodation makes sense. There is only so much land. There is only so much time. And if we can be humble, inclusive and brave, there is an opportunity for progressive populism to claim very valuable territory, in every sense.

The Trump phenomenon is about more than frustrating policy. It presents a moral challenge, a spiritual one, rooted in division. The best response is a fervent restatement of our shared stake in the commonwealth and the earth to which we will all return. Finding common ground, and reconciling it with our higher principles, is what the land has always demanded of us, and it is what it is offering us now.

When you stand on Mormon Row, you notice how close together the deserted houses are in that immense space. Even on the frontier, it seems, people have always sought some communion with the other. You get back into car, consult the map, and realize that Highway 89 travels north to an interstate that runs from Seattle to Boston, goes through Sioux City and Buffalo, Cleveland and Chicago–the very different outposts of our one and only place. The distances are great but they can be traveled. You just have to plot a course and start driving.

This article is part of City Limits’ Mapping the Future project, which covers the city’s housing crisis and investigates how power, inequality and history shape New York’s decisions over how to use land.