Affordable for whom? It is not just a question from communities within the footprint of every proposed rezoning in New York City. It is a question that is being asked across the nation.

More than in any campaign in recent memory, housing has become a key topic in the 2020 presidential race, reflecting a national housing crisis spanning from megacities like New York and San Francisco to smaller urban centers like Cleveland and rural areas like Randolph County, Georgia.

According to some research, home prices in 70 percent of the country are more than average household can afford. The Pew Charitable Trust found that in 2015, 38 percent of all renter households were rent burdened, an increase of about 19 percent from 2001. In South Bend, Ind., where Democratic hopeful Pete Buttigieg is mayor, there are 400 homeless households. In former Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s town, there are nearly 60,000 people living in homeless shelters. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, almost 7 million housing units are needed to make up for the lack of affordable housing stock in the country.

Last June, the Trump administration took steps that could have a heavy impact on the future of housing, such as creating a White House Council, chaired by HUD Secretary Ben Carson, which will look at ways to reform local zoning laws that prevent the construction of multifamily housing units. Six months later, HUD proposed a revision to the Obama administration’s anti-discrimination Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule; Secretary Carson proposed that rule’s implementation and method be left up to local jurisdictions rather than the federal government.

Some candidates have come up with comprehensive, ambitious housing plans while others have proposed more modest responses. Housing policy experts and advocates say this is the first time in modern history that housing has become a main presidential issue and also the first time moderators asked a question about affordable housing during a nationally televised Democratic presidential debates. “The core of the crisis is the lack of affordable housing for lower income households and voters are interested in knowing what candidates are planning. We took a poll and 76 percent of our voters wanted to see a housing plan and what the candidates are planning to do about this crisis before they vote,” says Diane Yentel, the president and CEO of National Low Income Housing Coalition. “In some cities and towns, there are enough apartments or housing–but there are not enough households who can afford those housing units.”*

It’s a multifaceted problem, and there are already federal programs in place aimed at addressing some aspects of it—although they appear to be falling short. The mix of targets and tools means the candidates’ plans share broad similarities and some striking differences.

“There’s actually quite a bit of overlap,” says Jenny Schuetz, a fellow at the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings. “The first is that they acknowledge that there are people who have low incomes who can’t afford housing. That’s basically a national problem that everywhere in the country, there are some people who just earn so little that they can’t afford to pay rent that would cover the operating costs on a basic apartment.”

“The second big box idea is that they need to talk about is the fact that in some places like New York and California, we haven’t been building enough new housing to keep up with demand,” and most of the candidates have acknowledged that,” adds Schuetz. “And then the third big point, is talking about racial disparities in housing markets: the past history of discrimination for things like mortgage lending and the degree of racial segregation that still exists in most cities.”

Of course, comparing what the candidates propose is just one lens. Whether the ideas are legally, financially and politically viable is another key test.

With that in mind, here’s a detailed look at the key housing proposals from candidates in the 2020 Democratic Presidential Primary.

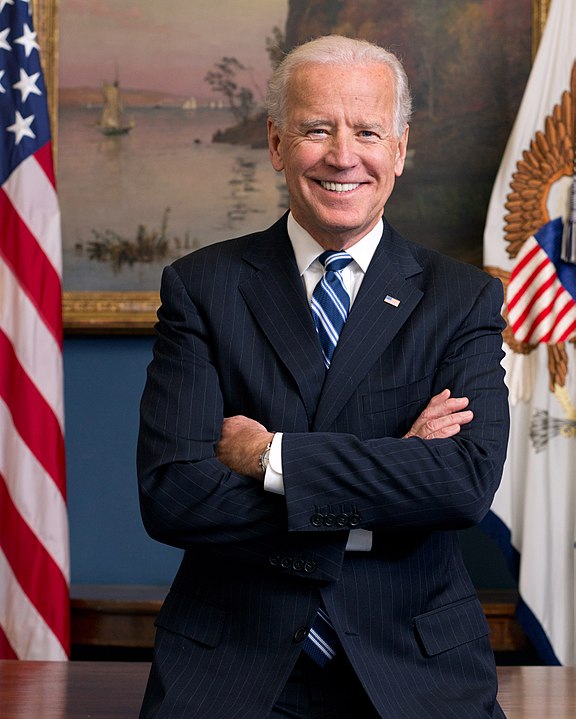

Biden: Few specifics

For 36 years, Joe Biden served as a U.S. senator until he became Vice President in the Obama administration. During his time as Senator, Biden co-sponsored or sponsored 11 pieces of legislation related to housing and development ranging from the National Homestead Assistance Act–which allowed the HUD secretary to purchase vacant, single-family homes–to the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1981 to include persons with disabilities including other measures. The Fair Housing Amendments Act, which expanded the forms of discrimination deemed violative of fair-housing laws, and enlarged the list of classes protected from housing discrimination to include the disabled.

Although Biden has not released a comprehensive housing plan like his rivals Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Bloomberg or Buttigieg — Biden’s campaign does focus on “investing in the middle class” through entrepreneurship and community investments.

“We have spoken to almost every candidate and I am bewildered that Biden has not put out a plan yet,” says Yentel.

The Biden campaign raised $61 million at last report. After retirees and law firms, the real estate industry is the third-biggest source of Biden’s contributions, according to Open Secrets. Dozens of smaller contributions in increments ranging from $2.50 to $5,600 were made by several New York real-estate developers. Other contributions include $3,500 from Roger Tackeff a Boston-based developer.

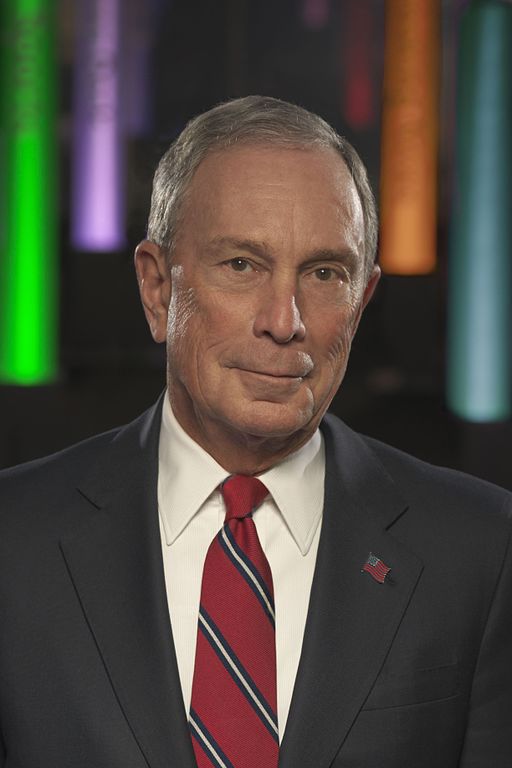

Bloomberg: A vow to cut homelessness

As mayor of the nation’s largest city for 12 years, Mike Bloomberg oversaw the largest public housing authority in the country, ran a homeless shelter system under a unique local legal right to shelter and helped regulate one of the largest biggest real-estate markets in the world. That gives him a deeper track record — for praise and/or scrutiny — than any of the other candidates in the race, even the other mayors (Buttigieg, currently, and, formerly, Sanders).

That record is decidedly mixed. Bloomberg rezoned 40 percent of the city, but some of those zonings prevented any increase in affordable housing. His housing plan generated lots of units (165,000) but many of them were unaffordable to the neighborhoods in which they were built. He made big promises on reducing homelessness, but cut off the supply of Section 8 and public housing to the shelters. Until late in his term, he did little for NYCHA.

Bloomberg laid out his housing plan for the nation in late January. He plans on guaranteeing housing vouchers to all Americans at or below 30 percent of the area median income, which is an estimated $28,830 for a household of three; help families stay in their homes by funding emergency financial assistance; expand federal grants to cities that implement effective eviction prevention programs; and create pilot programs for tenant counseling and legal-advice services. He would also raise the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and increase the Child Tax Credit for low-income households.

For access to housing, Bloomberg plans on recruiting more landlords into the voucher system and reducing the red tape within that system. He says he will use regulation and incentives to mitigate discrimination by landlords. He will also establish navigator services to help tenants find and secure housing.

Additionally, Bloomberg plans to cut the homeless population in half using existing federal resources coupled with initiatives by local governments. He wants to double federal spending on homelessness from under $3 billion to $6 billion annually. He says he will increase federal support for housing-first strategies and provide housing-search support and short-term rental assistance.

As preventative measures, he wants to expand the promotion of rapid-rehousing and permanent supportive housing, providing stability to the chronically homeless to address issues such as substance use disorder and mental-health services where needed and serving as a bridge to rental assistance. He will also integrate homeless support with critical “wrap-around” services and expand federal grants to cities that implement effective homelessness prevention programs.

In order to increase housing supply, Bloomberg plans on increasing funding for the Low Income Housing Tax Credit and prioritizing “new transportation funding for areas that have undertaken progressive zoning reform and reward municipalities that support affordable housing development in neighborhoods with good schools, transportation, and economic opportunity.” He will also provide funding for public housing by streamlining the Rental Assistance Demonstration program and increasing funding to the National Housing Trust Fund. Additionally, his plan will provide resources to help homeowners, building owners, and tenants for energy-saving renovations. He will also increase funding for energy retrofits and fully fund the existing Low-Income Home Energy Assistance program which helps mitigate home energy, weatherization and energy-related minor home repairs costs.

For tenants, Bloomberg wants to help renters become homeowners through a pilot program targeted to assist people with down payments for new homes, provide federal matching funds to offer all residents of the 100 communities as down payment and expand access to financial services. His goal includes one million new African-American homeowners.

For local governments, Bloomberg wants streamline investments to address the housing crisis by building on President Obama’s “Strong Cities, Strong Communities” initiative by driving an interagency effort from the White House. The Obama 2011 initiative was created to give technical assistance to local governments in order to execute their economic vision and strategies through public and private partnerships.

Bloomberg, a billionaire, is financing his own campaign (to the tune of $200 million so far) and is not accepting contributions.

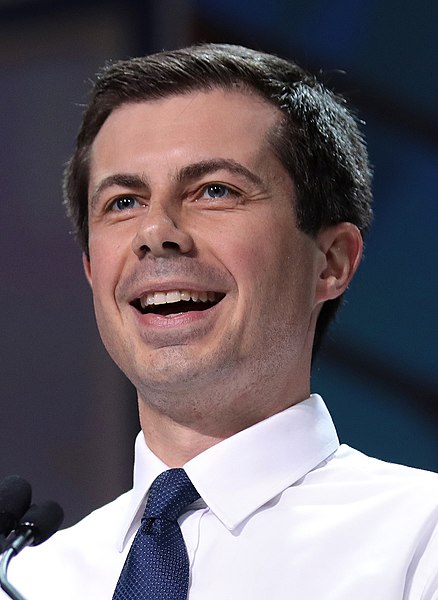

Buttigieg: Douglass Plan targets vacant-land potential

Decades younger than most of his presidential rivals , Pete Buttigieg came onto the campaign stage with experience as mayor of South Bend. His housing plan was released last year November along with several other plans to help middle-to low-income households by lowering child care costs, making college more affordable, lowering health care costs and furthering consumer rights protections.

Buttigieg’s housing plan is similar in scope to Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren’s housing plans. He will invest $430 billion to create access to affordable housing for over 7 million households and to create an additional 2 million housing units through creation and preservation initiatives. He also plans on working to reform local zoning laws. He wants to also invest in homeownership and is looking to facilitate homeownership of one million low-income households.

Refoming zoning is a common theme among the Democrats. Schuetz says this is new territory for federal policy. “ Because that’s really new, it’s hard to say at this point that any of those are more likely to succeed or even more likely to get adopted,” she says.

Another Buttigieg plan is to target redlined neighborhoods part of a comprehensive plan, known as the Douglass Plan, to mitigate racial and income in equities, particularly in communities of color. The Douglass Plan lists several initiatives ranging from criminal justice to health equity reforms.

Within the Douglass Plan, Buttigieg’s housing agenda includes the “Community Homestead Act” in which cities would apply for federal funding to operate land banks to acquire vacant properties and provide them to low-income families under a 10-year residency obligation.

Schuetz notes the Douglass Plan offers more to cities like South Bend or Baltimore or Detroit where there are swathes of land with city-owned houses in certain poor conditions, but was not tailored for larger cities where vacant space is rare.

It is not the first time Buttigieg has pushed to create housing. After he was elected to Mayor of South Bend in 2011, he created a task force to analyze the city’s vacancy stock which identified 1,900 vacant and 1,275 abandoned properties to renovate and reuse. In a report, similar to the Douglass Plan, the task force recommended establishing a land bank to encourage neighborhood revitalization efforts such as renovating homes with violations. In response in 2013, Buttigieg launched a “1,000 Homes in a 1000 Days” initiative with a budget of $10.5 million dollars funded by HUD’s Community Development Block Grant program, the Neighborhood Stabilization Program, and the state’s Blight Elimination Program, a program to bring up property value through revitalization efforts.

According to HUD, the initiative has met with some success. The city handled 1,122 houses: 427 were repaired, 569 were demolished, 10 were deconstructed, six were set aside for repair by community development corporations, and 110 were under contract for demolition.

Despite the success, the initiative also came under criticism for displacing some families from debilitated housing, instead of fixing their homes. The South Bend city administration argued that those homes had not been occupied for over 90 days, according to South Bend Tribune.

Buttigieg’s campaign fundraising has topped $76 million, with an estimated $932,988 from individuals connected to real estate groups, according to Open Secrets.

Klobuchar: A broad if modest plan

Senator Amy Klobuchar’s rise began when she became Minnesota’s Hennepin County Attorney. She became the first woman elected Senator in her state in 2006 just a couple of years shy of the 2008 foreclosure crisis. At the cusp of the crisis, Klobuchar co-sponsored several Congressional measures ranging from the bills to protect mortgage applicants to an amendment to the tax code allowing some flexibility for homeowners who originally financed their mortgages through a qualified subprime loan. Since then, she has cosponsored several measures to mitigate homelessness, end discrimination against victims of domestic violence, and create easier access to the federal housing voucher program, among over 30 other housing and development bills and amendments.

Akin to the housing plans proposed by Buttigieg, Warren and Sanders, Klobuchar’s housing plan is focused on creating affordable housing, mitigating homelessness and creating paths to homeownership but she focuses on tweaking several existing federal programs.

Klobuchar plans to fight housing discrimination by creating a new federal grant program for access to free legal counsel for people facing evictions; prohibiting discrimination based on income source or the blacklisting of tenants who have been evicted in the past; modifying the current Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule and restoring the Office of Fair Lending and Opportunity to monitor fair lending practices (whose authority has been reduced by the Trump administration).

For tenants, she plans on expanding rental assistance for affordable housing in rural towns by improving access to existing federal programs, and through the purchasing power of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, her administration will encourage lenders to serve rural mortgage markets. Additionally, she will expand support for affordable senior housing and direct affordable housing programs to allow retrofitting of rental housing for seniors.

She also has plans for major investments in the Housing Choice Voucher pilot program, which allows families to use their vouchers in higher opportunity neighborhoods. Additionally, Klobuchar plans on tackling “outdated” zoning policies by incentivizing cities who change their zoning policies with federal housing and infrastructure grants. As a path to prevent future evictions, she wants to create a personal savings account called “UP Accounts” for retirement and emergencies. Under her UP Accounts plan, employers will set aside at least 50 cents per hour worked to help people “build more than $600,000 in wealth over the course of a career.” The funds could also be accessed during emergencies that cause delayed payments for rent.

Klobuchar also plans to expand the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit for developing affordable rental housing and investing in homeless assistance grants that provide emergency and long-term housing.

For homeowners, Klobuchar would also invest $40 billion in the national Housing Trust Fund (HTF) annually to support the construction, maintenance and operation low-income households, which rural areas and Indian country.* She proposes a new federal tax credit, similar to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, to encourage investment in family-owned homes in distressed neighborhoods. She also wants to build on existing programs to allow certain types of rental housing assistance to be used for homeownership expenses and also plans on proposing legislation that will expand access to capital for down payments. She also wants to allow credit bureaus to use on-time payment data from cell phone bills, utilities, and rent in calculating credit scores so it is easier to build credit.

During the first 100 days of her presidency, Klobuchar plans on strengthening Community Reinvestment Act protections, developing policies to encourage financial institutions to make loans and investment in local communities. Klobuchar also wants to focus on educating first-time homebuyers through improving education programs that especially target communities with low levels of homeownership. Klobuchar also plans on reversing the Trump Administration’s proposed changes to federal housing subsidies and updating regulations for reverse mortgages, especially for seniors.

Her plan for funding some of these existing and new programs will come from raising the capital gains rate to the income tax rate for households making over $400,000, and part of her infrastructure plan, which includes plans for housing, will raise the corporate tax rate to 25 percent.

According to the Federal Election Commission (FEC), Klobuchar’s campaign has raised an estimated $29 million dollars. Her campaign has raised an estimated $300,741 dollars from the real estate industry ranging from a maximum of $2,800 to even one dollar in donations, according to Open Secrets and the FEC.

Next to Biden’s punt, Klobuchar offers the most modest plan among the major Democratic candidates.

Sanders: Rent control and more

Last year in September, Senator Bernie Sanders introduced a $2.5 trillion plan to mitigate the growing housing crisis across the country.

Sanders plans to invest $1.48 trillion in the National Affordable Housing Trust Fund in order to create, preserve and rehabilitate permanently affordable housing units within mixed-income development. An additional $400 billion will be invested to build 2 million mixed-income social housing units also administered through the National Affordable Housing Trust Fund. He also plans on investing an additional $500 million dollars in the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Section 515 program, an existing rural rental housing loans program to provide affordable rental housing for very low-, low-, and moderate-income families, elderly persons, and persons with disabilities.

Sanders calls for increasing funding for the Indian Housing Block Grant Program to $3 billion to build, preserve, and rehabilitate affordable housing in Indian country. Sanders also plans on investing $70 billion dollars in improving public housing, including to provide broadband services, and wants to repeal the Faircloth Amendment which does not allow HUD to construct new public housing units.

On Section 8, Sanders plans on fully funding the rental assistance program with $410 billion dollars over the next 10 years and making it a mandatory funding program for all eligible households. He also plans on expanding and strengthening the enforcement of the Small Area Fair Market Rent rule, which reforms voucher payments to help recipients move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods.

When it comes to tenant protections, Sanders’ proposal for national rent regulation would cap annual rent increases at no more than 3 percent while allowing landlords to apply for waivers if significant capital improvements are made on the property.

“Bernie Sanders has a proposal for what’s essentially nationwide rent-control, which is way outside the box of anything that’s been discussed before and I’m not totally clear whether that’s constitutional. And [it] would be very difficult to implement,” Scheutz says.

He also plans to implement a “just-cause” requirement for evictions. Additionally, he wants to provide $2 billion towards states and localities’ “right to counsel” programs for tenants facing evictions or foreclosure proceedings, or at risk of losing their Section 8 rental assistance.

Sanders also wants to streamline the review process and direct funding towards implementing fair and inclusive zoning ordinances with a focus on communities that face gentrification. For example, he proposes to place a 25 percent “house flipping” tax on speculators who sell a non-owner-occupied property, if the property is sold for more than it’s purchase price within within years of the procurement. Another proposal from Sanders will impose a 2 percent Empty Homes tax on the property value of vacant, owned homes.

He’s called for creating an independent agency to protect Section 8 renters from discriminatory landlords, fully funding the existing Fair Housing Assistance and Fair Housing Initiatives Programs at $1 billion over the next 10 years and ensuring formerly incarcerated residents are not excluded from public housing options.

Sanders wants to use 25,000 National Affordable Housing Trust Fund units in the first year for homeless households and also double the funding for the McKinney-Vento homelessness assistance grants to over $26 billion over the next five years to build permanent supportive housing. Additionally, he plans on providing $500 million in funding to states and localities for homeless outreach programs.

Sanders also wants to invest $50 billion over 10 years to provide grants for community land trusts and other shared equity homeownership models and invest an additional $15 billion to enact a 21st Century Homestead Act, which will revitalize abandoned properties and historically disadvantaged communities. For first-time home buyers, he wants to invest an additional $2 billion in USDA and an additional $6 billion in HUD to create a first-time homebuyer assistance program that will increase home ownership.

Sanders; campaign has raised the most money—$110 million—among his Democratic counterparts for the 2020 presidential elections. According to Open Secrets, almost $380,000 was donated by members of real-estate groups.

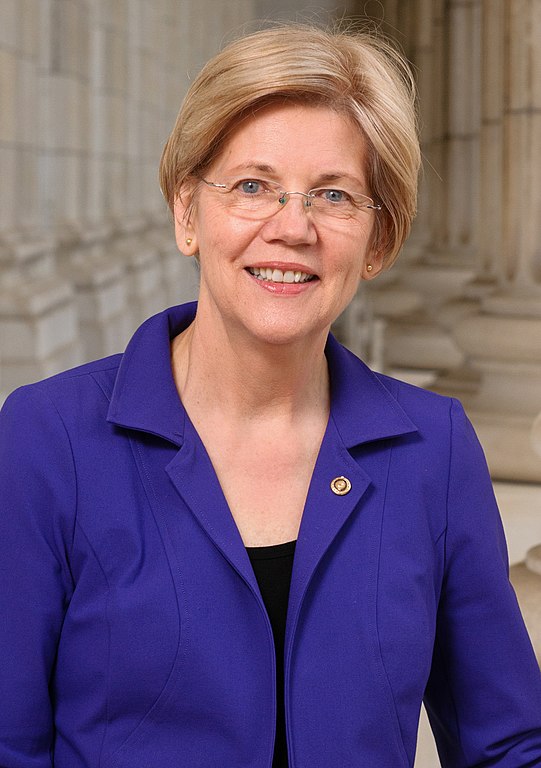

Warren: Aiming to limit Wall Street’s role

Sen. Elizabeth Warren got her start as an academic and became an advisor to the National Bankruptcy Review Commission in the 1990s. But her profile grew after she spoke as a proponent of heavier regulations on banks, especially after the role they played in the 2008 financial crisis.

Her plan revolves around four main goals: reducing rents for lower- and middle- class families; closing the racial barriers to housing that the federal government created decades ago with redlining; removing other kinds of discrimination from affordable housing; and finally, ending Wall Street’s heavy influence on the housing market.

Warren’s plan promises $500 billion over 10 years to build and rehabilitate affordable housing, with almost all of that going to the Housing Trust Fund, a HUD affordable housing production program. The leftover cash includes over $500 million going into the USDA’s Rural Housing Service, $2.5 billion into the Indian Housing Block Grant and the Native Hawaiian Housing Block Grant, and $4 billion into creating a new grant called the Middle-Class Housing Emergency Fund, designed to help fund housing construction for middle-class families specifically in areas where affordable housing is scarce.

A large portion of the $500 billion will be shouldered by private-public partnerships, which puts Warren in line with President Obama’s housing policy. To pay for the rest, the bill proposes a lower cap on the estate tax. Instead of taxing inheritances starting at $22 million, Warren proposes the tax start at $7 million, adding about 14,000 more multi-million dollar families to the pool of funding.

Warren promises to curb cities’ exclusionary zoning policies, like mandatory parking requirements, development fees or minimum lot sizes, which a report from 2015 says caused a massive increase in segregation. Warren’s plan to incentivize cities to axe these policies? Dangle a $10 billion carrot. Her bill proposes a new grant program that cities can apply for in order to build infrastructure, schools or parks.

Warren also plans to dismantle the effects of redlining. Warren proposes a substantial housing grant for residents in affected neighborhoods, provided that they have lived there for four-or-more years, qualify as low-income and are first-time home-buyers. The grant is aimed towards eliminating or easing the cost of a down payment on a home for minorities in disadvantaged areas. She also plans on expanding rights under the Fair Housing Act, which currently prohibits landlords from discriminating on the basis of sex or race. Her bill proposes to expand the act to include sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status, veteran status, and the source of one’s income, like a housing voucher.

When the FHA acquires single-family homes through foreclosure, it often sells those homes to private equity firms like Blackstone. These firms, in turn, will hike up the price of those homes. Warren’s plan aims to stop this cycle. Warren would mandate that a minimum of 75 percent of these foreclosed homes are sold directly to an individual owner/occupant, or to a community group that will rehabilitate the home and sell it directly to an owner/occupant.

Her plans for tenants focus on rent-burdened households by investing $500 billion over the next 10 years to create, preserve, and rehabilitate over 3 million affordable housing units for lower-income families and her plan would lower rents by 10 percent.

According to the FEC, Warren has raised $82 million. Her campaign has seen an estimated $255,181 dollars from members of the real-estate industry, per Open Secrets.

A broader discussion

As part of the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s campaign “Our Homes, Our Votes: 2020” which started last year, the national housing advocacy group has issued a list of recommendations it hopes will guide candidates and, eventually, the next presidential administration.

The NLIHC recommendations are four-fold. The first is to preserve and produce deeply affordable homes to meet the 7 million unit shortage—at a cost of at least $40 billion, plus another $50 billion dollar investment in repairing public housing. The second policy is funding rental cash assistance and the third recommendation is emergency cash assistance for households who may have faced a medical emergency and lack the funds to pay rent for a period of time. The last policy recommendation is to protect tenants from all discrimination and abuses.

Schuetz believes the housing policy discussion needs to expand even more, to discuss the environmental impact—especially in the context of climate change—of building housing in car-dependent suburbs, and to address the role of housing value in perpetuating the racial wealth gap.

“Most middle income households, their largest financial asset is the equity in their home that’s been pretty detrimental to African-American and Latino households who are less likely to be homeowners or they become homeowners later in life and tend to buy houses in neighborhoods where prices don’t appreciate as much,” she says. “So the homeownership strategy has created this very large racial wealth gap, and they’re sort of nibbling around the edges of that, but not actually addressing the fact that there are some limits to using homeownership. None of them have explicitly linked this to is there another way that we can help Americans save money and develop wealth that’s not tied to home ownership.”

* Editor’s Note: The original of this story has been clarified to include Sen. Klobuchar’s plans for the National Housing Trust Fund, and corrected to revise an erroneous reference to the NLIHC’s 2020 campaign, which was due to an editing error, and Yentel’s quote to resolve a transcribing error.

Read deeper:

NPS, NYCHA, DVIDSHUB, Slowking

On City Streets and in Wild Landscapes, the Fight for America’s Soul in 2020 is About Land

3 thoughts on “This Year, Running for President Means Talking About the Housing Crisis”

After the state of NY has effectively given all property rights to tenants, I will never vote for anyone who promotes rent control – so goodbye Sanders and Warren.

The federal courts will ultimately throw out NY’s new tenant laws as an unconstitutional taking.

Klobuchar’s plan isn’t really that modest. It would send much more (much-needed) subsidy for housing and homelessness than Bloomberg, Buttigieg, or Warren.

https://www.cssny.org/news/entry/how-will-the-democrats-housing-plans-affect-new-york-city