Read the original story in Japanese at Shukan NY Seikatsu

Translated and condensed by Rebecca Suzuki

With the beginning of the new year, the Heisei Era has come to an end in Japan, marking the start of the Reiwa Era, whose new emperor took the throne last spring. This year also marks the 160th anniversary of the first Japanese Embassy visit to the United States in 1860, and to look back on the milestone visit, Shukan NY Seikatsu dug through rare records archives to learn more.

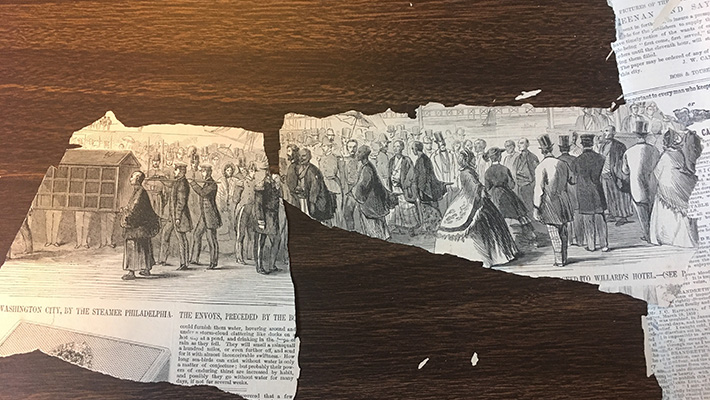

Newspaper clippings about these events were preserved at the main branch of the New York Public Library at Bryant Park. The papers had to be handled with the utmost care, as they were on the verge of falling apart.

Following the Treaty of Amity and Commerce signed by the U.S. and Japan in 1858, the Japanese embassy sailed to Washington, D.C. in order to exchange the treaty’s instruments of ratification with the U.S. State Department. The group, which included three Gaikoku Bugyo — commissioners appointed by the Tokugawa shogunate to oversee trade and diplomatic relations with foreign countries — and a crew of around 80 samurais.

They boarded the steamship USS Powhatan and departed the shores of Shinagawa in January 1860. En route, they were confronted by a storm that caused them to take a brief detour to Honolulu, where they met with King Kamehameha IV, who reigned over the country of Hawaii at the time. The ship finally reached San Francisco on March 8th, and was met with a warm welcome. After staying in San Francisco for nine days, the embassy headed to Panama and Cuba by ship and then to Washington, D.C. Since the Panama Canal did not exist yet, they crossed the isthmus by rail in order to reach the Atlantic Ocean. It was the first time the Japanese embassy rode a train.

The embassy arrived in Washington, D.C. in early March. When the ship reached the harbor, the samurais were ushered onto carriages and taken to The Willard Hotel led by a cavalry, military band, and military column. On the way, enthusiastic spectators threw bouquets and rang bells. At the Washington Willard Hotel (which still exists), the samurais tried ice cream—a foreign delicacy, after lunch. Some wrote about the dessert in their journal, describing it as “a sweet ice dessert that melts in your mouth.” Perhaps the few Japanese nationals who had made their way to America before the embassy had already tried it before, but this is the first recorded instance of a Japanese person trying ice cream.

In D.C., the U.S. government spent around $50,000 ($1.5 million in today’s money) to welcome the embassy, including a reception at the White House. On March 28, the embassy met with the 15th president of the United States, President James Buchanan. At the reception, the three commissioners wore traditional samurai clothing called kariginu along with their yellow-green eboshi, or headgear, and a long sword at their side.

The embassy stayed in Washington, D.C. for three weeks, during which they visited places like the Smithsonian museums, the U.S. Capitol, and the Washington Navy Yard. After that, they made their way to Baltimore and then to Philadelphia, where they toured the United States Mint. Finally, they headed to New York.

The embassy arrived in New York on June 16. They once again received a huge welcome, with a “Samurai Parade” along Broadway. The U.S. military and the samurais, dressed in formal clothing, marched side-by-side in the parade, which began downtown and went up to Union Square. The Japanese flag waved alongside the American flag, and more than 500,000 spectators flocked to watch. Some watched the parade with their heads sticking out of building windows, and some even climbed on top of telephone poles to catch a glimpse. In an article from the New York Times, the parade was described as “a glorious event that will go down in state history.”

In the evening, a reception hosted by the state of New York took place at the Metropolitan Hotel, which was located in SoHo. The embassy then met with the governor and mayor and also toured Central Park, visited universities, and went sightseeing. The New York Tribune published a feature on 70 of the samurais.

Among the parade’s marchers was a young man named Tateishi Onojiro, who came along on the mission as a translator’s apprentice. Skilled in linguistics, Onojiro learned English at his job and he also observed Western mannerisms. His nickname was “Tamehachi” and his Japanese coworkers called him “Tame.” On board the ship, the naval officers misheard this as “Tommy,” which is how Onojiro came to be known in America.

At only 16 years old, he was the youngest samurai of the group, and was popular everywhere he went. During the parade in New York, he waved the handkerchiefs that he had received from American women, and countless love letters awaited him at the hotels he stayed in. Both the New York Times and New York Tribune wrote articles about Tommy. He even had a song named for him.

In New York, the visiting samurais were so popular that there were even theater performances and songs about them. By the summer of 1860, samurai-inspired merchandise was being sold, and a cocktail named “Japanese” was born. Renowned American poet Walt Whitman wrote a poem after witnessing the Samurai Parade, called “A Broadway Pageant,” published in Leaves of Grass.

New York was the final destination in the U.S. for the embassy. After, they crossed the Atlantic Ocean and stopped by current-day Cape St. Vincent and then Angora, made their way around the Cape of Good Hope on the tip of Africa, then to Jakarta and Hong Kong before reaching Japan and concluding their eight-month trip.