NY State Senate

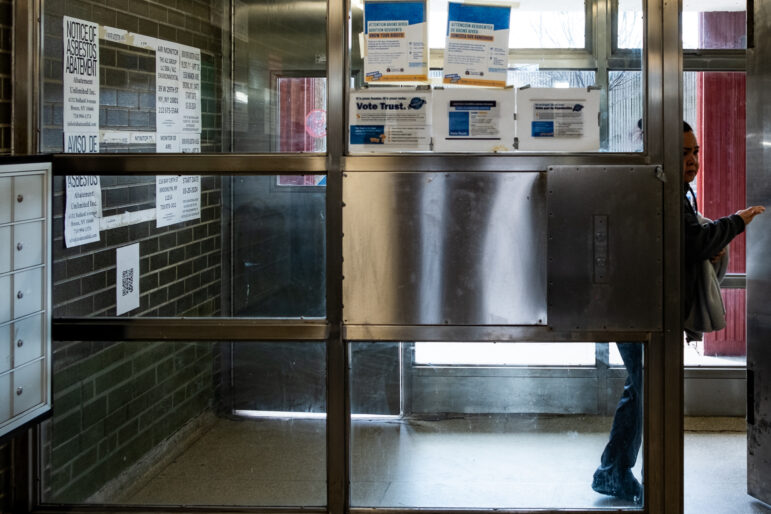

State Sen. Kevin Parker has authored two bills to give Brooklyn homeowners protection from aggressive real-estate solicitation.Owner-occupied housing is the new front in the battle over the future of gentrifying neighborhoods, and advocates hoping to fend off aggressive investor interest think they might get a new defensive weapon: a cease-and-desist zone covering all of Brooklyn.

In cease-and-desist zones, homeowners can join a list of property owners whom real-estate companies are prohibited from soliciting to sell. It’s a mechanism that has been on the books in New York State for at least 80 years. In 1939, all of Queens was declared a cease-and-desist zone.

State Sen. Kevin Parker, a Brooklyn Democrat, is pushing to make all of Brooklyn a cease-and-desist zone. Parker introduced laws to that effect during the 2017-2018 legislative session that went nowhere in a Republican-controlled Senate, and tried again in 2019, after Democrats took charge, to no avail. He re-submitted the bills in January, and they currently sit before the Judiciary Committee.

Worries about investors

Owner-occupied housing plays a complex role in the gentrification story. On one hand, owners who sell amid rising values can enjoy windfall gains, and—unlike renters—represent a part of the incumbent population that can profit from climbing real-estate values. On the other hand, when Black and Latino homeowners sell their homes, they can contribute to demographic change in the neighborhood, and those former homeowners sometimes struggle to find new housing they can afford, even with sale money in their pockets.

When the buyer is an investor, the sale can contribute to speculation in the community. Investors are increasingly important players in small-home sales: In 2012, according to the Center for New York City Neighborhoods (CNYCN), only 8 percent of small home and condo/coop sales in New York City were to investors, but by 2017, investors were the buyers in 18 percent of those sales. Many owner-occupied homes include rental property, so tenants can be affected by these moves, too.

Advocates contend that aggressive pitches from realtors sometimes pressure homeowners who would not otherwise sell into taking a deal, and sometimes a bad one. “It’s not just, like, one person knocking on your door. If you’re in a community that’s gentrifying and that’s undergoing price increases, it’s more of a steady flow of solicitation,” says Caroline Nagy, the deputy director for policy and research at CNYCN. “It’s making you feel like you’re no longer welcome in your community. ‘It’s time to cash out. Other people are moving in. It’s time to go.’”

Nagy adds: “We’ve seen some bad actors target particularly vulnerable people: seniors, people with limited English proficiency, people at risk for foreclosure. These are people who it’s more likely [to] be taken advantage of, that they’ll be scammed.”

RE industry opposes

The cease-and-desist law is supposed to prevent that. If members of a community can demonstrate to the state’s Department of State that aggressive real-estate tactics are a problem in a specific area, the agency can declare a cease-and-desist zone for five years.

Currently, there are cease and desist zones in Auburndale, Bayside, Bay Terrace, College Point, Malba, Murray Hill, North Flushing and Whitestone in Queens; the Country Club area of the Bronx and the village of Chestnut Ridge in Rockland County.

Past zones have covered Mill Basin, Mill Island, Bergen Beach, Futurama and Marine Park and, separately, Canarsie in Brooklyn, Bronx community boards 9,10,11 and 12 and all of Queens.

The real-estate industry opposes the creation of individual zones by the Department of State as well as the new legislative efforts to create geographic prohibitions.

In its legislative agenda last year, the New York State Association of Realtors celebrated the failure of Parker’s bill, noting that NYSAR “strongly opposes cease-and-desist zones which specifically target licensed real estate professionals while ineffectively allowing unlicensed individuals and firms to continue engaging in unwanted practices unfettered.”

“Real estate marketing practices are consistent with other professions and businesses, making it improper to single out one type of business,” the association continued.

When the DOS was considering whether to impose the Rockland zone in 2018, NYSAR’s president CJ DelVecchio, submitted testimony opposing the move. “[P]unishing all real estate licensees practicing within Rockland County due to the actions of a handful of practitioners and non-licensed individuals is overreaching. Law abiding real estate brokerages, which are significant contributors to Rockland County’s economy, must not be singled out and halted from conducting legitimate business practices,” it read. “We believe the proper course of action is for the Department to utilize the investigatory powers and remedies within its licensing authority to appropriately address any illegal activity or violation of real estate license law.”

A fuzzy law?

It’s unclear, however, that the existing mechanism’s teeth are as sharp as NYSAR describes them.

Not only is the process for declaring the zones fuzzy—the DOS website says next to nothing about how to go about petitioning for a new zone—but, even when a zone is declared, homeowners must add their names to the list to give it meaning. That depends on a public outreach campaign alerting people that the list exists. Only 65 homeowners have added their names to the Bronx list, but there are 156 on the list in Rockland County, and the Queens cease-and-desist zone has 1,175 subscribers.

Once on the list, homeowners have to report violations and hope the DOS enforces the law aggressively. While the agency tells City Limits it “has pursued many violations since 2000,” it doesn’t track data on cease-and-desist cases. A search of the DOS archive of administrative law decisions turns up a few dozen cease-and-desist cases, few of them recent. In 2011, an investigation determined that two realtors had “demonstrated untrustworthiness and incompetency” in violating the cease-and-desist law; it fined each $250. In 2006, another investigation about an ad for real-estate consulting services placed on the doorknob of a house that was on the cease-and-desist list found, oddly, that “it is reasonable to conclude that someone had picked it up at another location and placed it on the [homeowner’s] door knob” and let the realtor off.

Of course, the lack of enforcement could indicate the law is rarely violated. But advocates believe the current system is unduly cumbersome. “The fact that you even need to go through the rigamarole of establishing a cease-and-desist zone seems like it shouldn’t be necessary,” Nagy says. “We can unsubscribe from unwanted emails. We can get on a ‘Do Not Call’ list. I don’t see why it should be any different just because they are at your home bothering you.”

A larger to-do list for homeowners

Parker has actually written two bills that essentially do the same thing. Neither has attracted significant support from Senate co-sponsors. S1253 would designate all of Kings County a cease-and-desist zone for five years; that’s co-sponsored by Sens. Roxanne Persaud and Julia Salazar. Salazar last year circulated a survey of homeowners about aggressive real-estate tactics.

Assemblymember Tremaine Wright has written an equivalent bill to S1253 in the lower house.

Parker’s other bill, S1256, would designate each Brooklyn ZIP code as a zone. Only Persaud has signed on to that one. Assemblymember Nick Perry authored the Assembly version.

Meanwhile, Assemblymember David Weprin has sponsored a bill that would make all of Queens a cease-and- desist zone. It does not appear to have a Senate equivalent, and the other three boroughs do not appear to be spoken for in parallel legislative proposals.

Cease-and-desist zones are part of a larger push for policies to support low- and moderate-income homeowners. CNYNC issued a detailed blueprint for policies to encourage equitable homeownership in September. In November, the Coalition for Affordable Homes and the Coalition for Community Advancement rallied in Brooklyn for a “homeowners’ bill of rights” that includes freedom from harassment, fair credit and a “flip tax” to discourage speculation in homebuying.

“I think the cease-and-desist zones are an important tool but one of many in the arsenal for communities that are seeking to develop stronger protections against an influx of investors,” Nagy says. The flip tax is another key proposal in which, Nagy says, advocates are seeing “renewed interest.”

6 thoughts on “Bill Would Make Brooklyn a Real Estate ‘Cease-and-Desist’ Zone”

Are Brooklyn homeowners that stupid and helpless? Just tell realtors ringing your doorbell that you aren’t interested in selling. Tear up mail solicitations from realtors. And grow up.

It is intrusive and abusive to have to shoo folks with cameras taking pictures of my brownstone or hang up or answer the doorbell when I am working. I am grown up. I don’t want to be harassed. Susan. Prospect Heights.

You tell them you are not interested and leaving your property to your offspring, you tear up flyers, discard letters of solicitation and these vultures actually got my job number and called me. This is harassment and must be stopped.

No Brooklyn homeowners are not stupid and helpless, it does not matter how many times you tell them you are not interested in selling , they still harass you with phone calls and freaking junk mail. What I do when they call me is to tell them where the hell to go. If its worth 2 million to them, its priceless to me and mines.

Phones calls can be a bit much, but just shred the mail!

Wish everyone who are in real needs, let them own a house and live happily ever after. God Bless America, God Bless Brooklyn.