Adi Talwar

A single-family home on Seabury Place in the Bronx. Houses like this were a key part of the city's housing strategy in the 1980s. Now there are calls for a new era of affordable homeownership.

The section of the Bronx just south of Crotona Park, where the elevated 2/5 train screeches along Southern Boulevard, does not seem particularly suburban. But that is where you will find Suburban Place, a one-block street featuring three ranch-style houses set on small yards. One has a driveway. One has a back deck. Walk around the block and down Charlotte Street and you’ll see more single-story homes, some with miniature lions guarding their front gates, and similar houses on Seabury Place and Minford Place and along Louis Nine Boulevard as well. It isn’t exactly Mayberry, but it also is not the look you’d expect at the center of the third most densely populated county in the United States.

Charlotte Street, of course, is where President Carter stopped to tour urban devastation first-hand in 1977, and where candidate Ronald Reagan followed in 1980. The single-story, one-family houses came a few years later. They were built to fill the void left by the arson and the government neglect of a previous era. Though they look out of place now in a city of growing density, those homes—and thousands more like them all around the city—were an ingredient in the prescription that brought New York City back from the dead.

Now, some experts say, it is homeownership that needs saving in New York.

Rising taxes and repair costs are squeezing many homeowners, especially seniors. Investors are injecting more cash into an overheated small-homes market, pricing out even middle-class families. Climate change demands expensive steps to make homes greener and safer that many owners simply cannot afford. A decade after the financial crisis destroyed billions of dollars of Black wealth in the city’s foreclosure hotspots, homeownership disparities continue to drive the racial wealth gap. And as gentrification transforms neighborhoods, few financial benefits trickle down to working-class renters.

In a blueprint released Friday, the Center for New York City Neighborhoods prods the city, state and federal governments to develop policies aimed at “a future where homeownership is a truly viable choice for working New Yorkers, where intergenerational prosperity is possible for low- and moderate-income families, and where new models of shared equity thrive.”

CNYCN’s sweeping set of policy recommendations charts a potential path for Mayor de Blasio to pursue during his remaining time in office. It also tees up a complex policy challenge for the people running to replace him in 2021—an issue with deep roots in history.

“I think homeownership has proven to be one the best ways to build wealth in this country, but it’s only been available to some,” says Caroline Nagy, deputy director for policy and research at CNYCN. “Communities of color have been systematically excluded, really as kind of a fundamental part of our nation’s history,” from Jim Crow to redlining to predatory lending.

“You can’t say that we’ve ever had a fair playing field or that we’ve ever done it right. I don’t want to give up on homeownership without a wholehearted effort to make its benefits realizable to all.”

A shrinking window of opportunity

Roughly two-thirds of New Yorkers rent their apartments, and a third own their homes—just about the mirror opposite of the national picture, where owners predominate.

There are stark racial patterns of homeownership in the city: 42 percent of White and 39 percent of Asian households own their homes, compared with 26 percent of Black and 15 percent of Latino households. There are also gaping differences among neighborhoods: On the South Shore of Staten Island, 83 percent of households are owner-occupied, but less than 4 percent are in the Fordham section of the Bronx, according to the NYU Furman Center.

Those overlapping disparities, which were stretched wider by the 2007-2009 foreclosure crisis, help drive the racial wealth gap that’s been a factor of life in the city for decades.

But recently, the path to homeownership in the five boroughs has become much more difficult over the past decade, as home prices grew far faster than wages. According to a 2016 report by the Furman Center, low- and moderate-income households made up 51 percent of the population but could afford only 9 percent of housing sales in 2014. Even middle-class households were priced out of 77 percent of sales that year.

A significant driver of the price surge is the increasing presence of investors in the market. In 2012, according to CNYCN, 8 percent of small home and condo/coop sales were to investors; in 2017, investors were the buyers in 18 percent of those sales.

Investors are especially active in the part of the market that might otherwise be affordable to lower-income people. Among sales that would have been affordable to a family with the city’s median income, which is $60,000, investors scooped up 9 percent of sales in 2008, and 20 percent in 2017. When it comes to one- to four-family homes, investors have been the buyer in the majority of sales every year since 2009.

Joel Raskin

No picket fence needed: A different model of urban homeownership is seen at Cooperative Village on Grand Street.

Pressure builds on owners

Though renters dominate and investors are invading the ownership market, there still are a lot of actual homeowners in New York: The 1 million owner-occupied households in the city are more than exist in 16 U.S. states. Research indicates much of that population is under threat.

More than a third of New York City homeowners spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs, making them officially cost burdened. According to CNYCN, nearly a third of owner-occupied homes in the city “have at least one maintenance defect, defined as water leaks, cracks and holes, inadequate heating, mice or rats, toilet breakdowns or peeling paint.”

The challenges—physical and financial—are especially deep in some places: CNYCN surveyed East New York homeowners and found that 63 percent have an unmet repair need. The New Economy Project found that in 2017 homeowners in communities of color in New York received pre-foreclosure notices twice as often as their counterparts in other areas.

And since the vast majority of senior homeowners have low or moderate incomes, many older homeowners face particular problems. Some of them find their way to Kim Lerner, the program director for benefits outreach at LiveOn, a citywide advocacy and service organization for aging people.

“They have found it impossible to survive in their home,” Lerner says of her clients, who overwhelmingly have paid off their mortgages but get overwhelmed by repair costs, taxes and other homeowner expenses. “They are in constant danger of having their electricity shut off, or their phone. It’s a constant crisis that they are juggling.”

The pressures are magnified by social trends: Sons or daughters can help with simple repairs, but only if they live nearby—and aren’t working multiple jobs. And then there is the danger of being “house rich and cash poor”: People with houses valued at $860,000 or more are not eligible for Medicaid, even if their month-to-month income is low and they need the help.

“What’s crushing is, sure, one thought is go ahead and sell the house,” Lerner says. “But it’s a challenge to find somewhere to move in and feel comfortable moving forward.”

As the city gets grayer, those challenges will grow. So will the issues created by climate change. Sea-level rise will soon put thousands more homeowners into the flood zone, and many homes in the most vulnerable areas are years behind on resiliency measures. Extreme heat will pose an increasing challenge for small homes that lack central air. And small homes produce 17 percent of the city’s carbon emissions.

All these risks don’t just affect homeowners: According to the Housing and Vacancy Survey, some 300,000 rental units exist in one- and two-family homes in New York.

Different plans for different eras

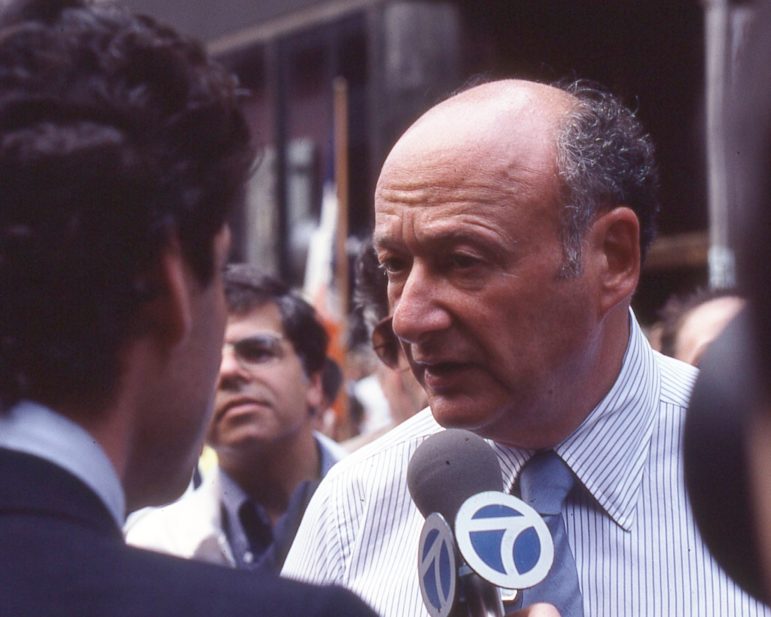

Bill Golladay

Mayor Koch's housing plan faced three problems— affordability issues, decreased population and a surplus of vacant land—that penciled-out to an elegant solution: low-density homeownership.

Hailing homeownership as “the backbone of the city’s stable working and middle class neighborhoods,” Mayor Koch in his 1985 State of the City speech boasted that his administration had “created thousands of low-income cooperative apartments” and “provided home ownership opportunities to thousands of working and middle class families through the support of … neighborhood building programs.” Homeownership, Koch said as he unveiled the first version of what would become his Ten-Year Plan, “must continue to be a keystone of any comprehensive city housing policy.”

It’s hard to pin down precisely how many ownership units were produced under the Koch plan, which emphasized rental housing, but one of the organizations he mentioned in 1985, the New York Housing Partnership, is credited with creating some 25,000. “When the Housing Partnership started in the late 1980s the focus was solely on getting [tax foreclosed] properties back into service via homeownership opportunities, and this was in all five boroughs of the city,” recalls Shelia Martin, chief operating officer of the Partnership. Back then, the city issued requests for proposals encompassing huge swaths of land. “It was, ‘We have this parcel and we’re looking to see 100 two-family homes on it.’ That was the operating premise.” The first projects were one- and two-family houses. As the city began to recover from the fiscal crisis and population started to rebound, the emphasis shifted to three-families. But there was still plenty of land.

Twenty years later, Mayor Bloomberg’s New Housing Marketplace affordability plan aimed to build and preserve a great deal of rental housing, but also set out to build 18,000 new homeownership units as well as preserve thousands more. That initiative faced a different city than Koch encountered. The big slabs of land were gone, forcing homebuilding onto costlier, smaller, more complicated sites where construction cost more. Then the financial crisis hit, and Bloomberg shifted his entire plan to emphasize preservation. Matt Murphy, a former deputy commissioner at the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development who now serves as executive director of the NYU Furman Center, says that shift was especially urgent when it came to ownership properties. “From 2009 to, say, 2013 it was all about just helping existing homeowners get out of being underwater, avoiding foreclosures,” he says.

According to HPD, Bloomberg’s plan ended up financing the purchase or construction of 6,600 homes and preserved another 26,000.

The growing alarm over affordability toward the end of Bloomberg’s tenure focused almost exclusively on the rental market. When de Blasio took office and unveiled his own housing plan, Housing New York, his blueprint matched that zeitgeist, but it did promise the launch of two new homeownership programs, the Neighborhood Construction Program (NCP) and the New Infill Homeownership Opportunities Program (NIHOP). When de Blasio revised Housing New York in 2017, he added the Open Door program—for affordable coops and condos—as well as the HomeFix program to help fund home repairs for low- and moderate-income owners. Last year, the administration took another step, boosting the amount of down-payment assistance under the HomeFirst program from $25,000 to $40,000.

According to numbers provided by HPD, the de Blasio plan has so far produced modest homeownership numbers: 2,040 new homeownership units, although more are in the pipeline. Some 23,000 units have been preserved. That’s a small share of the 135,000 units the de Blasio plan has generated overall. The money breaks down similarly: Roughly $850 million in city money has been spent on homeownership out of $5.9 billion on the entire plan.

An aggressive policy platform

Adi Talwar

A Build it Back site in Sheepshead Bay. Post-Sandy recovery initiatives are examples of city policies that affect homeowners outside of the housing plan.

The Center for New York City Neighborhoods’ strategy calls for a far more aggressive approach, including expanded down-payment assistance, supporting innovative financial tools for homebuyers, enforcing stronger fair housing laws, and expanding the use of community land trusts. Among dozens of ideas, the center calls for giving tenants a “right of first refusal” to purchase before their building is sold.

CNYCN also calls on the city to take stronger steps to help existing homeowners, like more foreclosure prevention, expanding repair programs, hooking seniors up to estate-planning advice, and working with healthcare institutions to help identify intersections between home-repair problems and medical issues.

Not that the city is the only player that matters. New York State created its own Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) fund in 2007 – the first in the country, and a potentially valuable tool in creating new paths to affordable homeownership. But the state has yet to actually fund it. The state has also failed to adjust its home-construction subsidy programs to allow for cost increases.

“In recent decades, state subsidies for homeownership have not kept pace with the high cost of housing and the effect of this can be seen in the displacement of low-and-middle income households from traditionally affordable neighborhoods throughout the outer boroughs,” says Karen Haycox, the CEO of Habitat for Humanity NYC. “While efforts to control staggering rents have redoubled, particularly in the last legislative session, what is still largely absent from the table is a progressive and forward thinking approach to homeownership. We must work to ensure that the choice of homeownership – the choice to remain and be part of a neighborhood’s growth – is available to all hardworking New Yorkers.”

Of course, government policy shapes the housing market in multiple ways, many of which aren’t part of any formal housing plan. Murphy notes that in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, city programs like Build it Back ended up impacting thousands of homeowners. One of the major “indirect influencers,” as he calls them, is the city’s tax structure.

“Something to keep in mind is that homeownership is pretty diverse. It means coop owners, condo owners and then it means smaller building owners and a lot of one-family and two-family homes,” he says. “The other thing to keep in mind is that you have a complex property-tax system that treats these owners differently.”

There’s broad consensus that the city’s property tax system is deeply flawed, rife with inequities among homeowners and between owner-occupied and other housing. To REBNY’s Gerhards, “the property tax system is inherently broken and is punitive to multifamily rentals.” Others focus on the disparities between private homes in gentrifying areas and other neighborhoods.

The de Blasio administration has talked for years about fixing the system, but appears to have little interest in doing so. A lawsuit working its way through the courts could force the city;s hand. Or de Blasio could punt a very thorny policy issue to his successor, who will have to figure out a way to maintain tax revenues while ironing the disparities out of the system—meaning there will be winners and losers, with low- and moderate-income homeowners right in the middle.

Clear goals needed

The concept of “homeownership” is laden with cultural and political baggage. There’s a shockingly resilient notion that homeowners are somehow morally superior to renters, or at least more reliable. That’s easy to dismiss. It’s harder to separate myth from reality when it comes to the ways homeownership is marketed to would-be owners – that living “the American Dream” means owning a home, and that doing otherwise represents a failure to provide for one’s family, or at least a missed opportunity to move from the fringes of the economy to mainstream. The aura around homeownership abetted the subprime lenders who plunged hundreds of thousands of families, and eventually the entire world economy, into crisis.

Ariel Aufgang, an architect active in affordable-housing development, believes the value attached to homeownership is an anachronism from post-war America, when it was believed that property values would rise inexorably, representing a no-brainer investment for families that tended to stay in one place. The modern reality of a more volatile market and a more mobile population make for a potential problem, Aufgang says: What if the market is down when you want to move? “It’s a shifting idea of what’s best for your own situation,” he says. “We don’t have to be so married to this conception that homeownership is the only route to the middle class.”

Basha Gerhards, a vice president at the Real Estate Board of New York, echoes that point. The reason why New York is mostly rental is because that’s what people want, she says. “Most people carry a lot more debt than they used to. More people want to move closer to their jobs,” she says. “From the developers’ perspective, that’s the product that people need. What people need in New York City is more rental housing. At the end of the day, more people need rental housing than need homeownership opportunities.”

But—if it’s actually “affordable”—homeownership does convey substantial benefits, some of which go to the heart of major policy debates in the city. According to CNYCN, were homeownership rates equalized among racial groups, the wealth gap between Whites and other would shrink considerably. Homeowners also share in the benefits of gentrification in a way that renters cannot and avoid many of the displacement risks. There are tax benefits, opportunities to leverage home value to pay for college and more.

“When affordable homeownership is properly underwritten and backed by city and state policy, the results are transformative,” says Haycox.

The trick, of course, is getting that affordable underwriting. As Murphy points out, the contours of the city’s economy make it difficult. “Homeownership is so unattainable mostly because of income inequality. So much of the inventory is so high priced because there’s so little available inventory, even to middle-income households,” he says. “Any city effort into homeownership is going to be a drop in the bucket.”

Indeed, cost is one reason why recent city housing policy has aimed more at the rental market. Another is density. The city wants multiunit buildings, and multiunit affordable housing opportunities have sometimes proven difficult: witness the two-dozen Housing Development Fund Corporation coops in the most recent round of tax-delinquent buildings the city targeted for transfer to third-party operators. HPD sponsored more than a thousand coop or condo units a year in the early 1990s, and averaged 190 a year during the Bloomberg era. The de Blasio years have seen an average of 17 units a year.

For better or worse, coop and condo conversions will now be harder in New York. With no fanfare, the landmark rent-regulation law passed in Albany last June also raised the threshold for coop and condo conversions: Instead of needing approval from 15 percent of tenants, 51 percent will need to sign off to go ahead with an application to convert. The idea was to stop landlords from using coop conversions as a new way to exit the rent-stabilization system. Since 1994, coop and condo conversions have removed 50,000 units from rent stabilization, about a sixth of the total number of apartments lost from the system.

The changes to the law, however, affect all housing – not just rent-regulated housing. “I think that really removes a path to affordable homeownership,” says Gerhards. Some affordable homeownership advocates wonder if the new law might be tweaked to create a way for disgruntled landlords who want out of the system to give tenants a shot at buying, with protection in place to shield those who still want to rent.

A different way to wealth

Mayoral Photo Office

Mayor de Blasio has tweaked his housing plan to create new tools for achieving affordable homeownership. Advocates want a deeper dive.

Affordable housing programs have to contend with scarcity—of land and of money—and the inevitable questions about fairness that scarcity creates. It’s one thing to use government resources to create an affordable rental apartment that will carry income restrictions for 30 years or longer, which over time could help multiple families afford to live in the city. It’s another to apply those same resources to create a private home whose owner, just because he won a housing lottery, could someday sell and recoup a potential windfall.

Of course, building wealth is one of the arguments for homeownership. This creates a difficult balancing act for affordable homeownership programs. “There’s an inherent tension that we see with homeownership: we want the housing to be both affordable and have the potential to build wealth,” Murphy says. Restrict resale values to ensure long-term affordability, and you reduce the amount of wealth a participating homeowner can build. Allow unfettered resales so owners can fully cash in, and affordability ends after the first owner.

The housing policy landscape is changing, however, in ways that emphasize a more sustainable kind of wealth-building. Much of the hope for new affordable homeownership rests on community land trusts, or CLTs. Where affordable housing projects in the past ended up subsidizing land that ended up under private control with uncertain prospects for long-term affordability, CLTs maintain permanent income restrictions and cooperative control. The Interboro CLT, for instance, is aiming to create cooperative homeownership opportunities for low- and moderate-income homeowners who’d be allowed to sell, but with restrictions on the resale value.

It’s a different model of homeownership, one founded on the likelihood of modest capital gains instead of the possibility of sudden riches. It’s not completely new—limited equity coops and cooperative complexes built in the early 20th Century, like the Amalgamated Houses of the Bronx, offered similar approaches.

As the city densifies, a new generation of coops aimed at low- and moderate-income families could align housing needs with planning priorities. The future of affordable homeownership in New York won’t look like Charlotte Street. But, as Nagy notes, “You don’t need a yard and a picket fence to take advantage of the benefits of homeownership.”

Still, there’s no free lunch. Were the city to adopt a more aggressive approach to creating affordable homeownership opportunities, it could reduce the overall number of units built or preserved under the Housing New York plan. But advocates have been prodding de Blasio for years to focus less on the goal of 300,000 units and more on serving the deepest needs in the market. Rentals for extremely low-income families is one such need. Homeownership for low- and moderate-income people is another.

“Homeownership is something that people want and need. There’s a bigger emphasis right now on rentals but people want to own and as expensive as it is, they’re still looking. And they hope that through some city program there would be affordable homeownership,” says Martin. The scale and the model seen on Charlotte Street might be outdated. “But homeownership isn’t dead. We just have to be a whole lot more creative in how to do it.”

No matter what, more inclusive homeownership alone won’t close the racial wealth gap or address housing segregation—putting more onus on other efforts, like the city’s Where We Live fair-housing initiative, to address some of the other drivers of systemic racism in New York.

A national issue

Statistics indicate that homeownership and urban life are growing increasingly incompatible: According to Rent Cafe, the number of U.S. cities where renters outnumber owners has swelled from 20 in 2006 to 42 in 2016. That reflects a broader set of housing worries that has forced the issue into the 2020 presidential campaign. Several Democratic candidates have issued detailed housing agendas. Their strategies focus primarily on renters, but homeownership is also part of the conversation.

Sen. Kamala Harris proposes a $100 billion fund to support Black homeownership. Sen. Bernie Sanders wants to offer grants to cities to create community land trusts. (A helpful guide to candidates’ plans is offered by the National Low Income Housing Coalition.)

CNYCN’s blueprint calls for modernizing the Community Reinvestment Act “to better ensure that financial institutions help meet the credit needs of all communities, with an emphasis on increasing lending to people of color in historically redlined neighborhoods” as well as expanding CRA “to cover online lenders as well as brick-and-mortar banks.” CRA reform is part of Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s housing plan, which also calls for a down-payment assistance program for first-time homebuyers “who live in a formerly redlined neighborhoods or communities that were segregated by law and are still currently low-income.”

Back in New York, housing issues could also be taken up by state elected officials, either in the spring 2020 legislative season or the legislative elections that will follow in the summer and fall. And of course, the 2021 mayoral race is already quietly underway, with candidates looking for new ways to frame and react to the ever-present worries about affordability in the city.

“I think the time is now to really take some bold actions. We are 10 years on from the foreclosure crisis. There’s concern about another recession possibly looming,” Nagy says. “I kind of feel like it’s now or never in terms of making this a priority and making real investments.”

The 2020 and 2021 elections do present opportunities. But, she adds, “there’s still time for the de Blasio administration to take some of this to heart.”

One thought on “Call for City to Take Aggressive Steps on Affordable Homeownership”

Encouraging home ownership is a great idea. But I don’t see the unfocused deBlasio administration getting behind it in a big way.

The price of land and labor is so high in NYC that there is no such thing as a low-cost 1/2/3 family home anymore. My small 1-family house on SI is valued at around $580k based on nearby sales, that’s cheap for NYC.

These 2 new fairly plain 2-family homes (replacing a torn down 2-family home) in my neighborhood will be listed at above $1M:

https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/178-Allison-Ave-Staten-Island-NY-10306/2084077032_zpid/

The builder of this nearby new 2-family home (on previously vacant land) expects to list it at $1.1M:’

http://a810-bisweb.nyc.gov/bisweb/JobsQueryByNumberServlet?requestid=2&passjobnumber=520357177&passdocnumber=01