Sadef Ali Kully

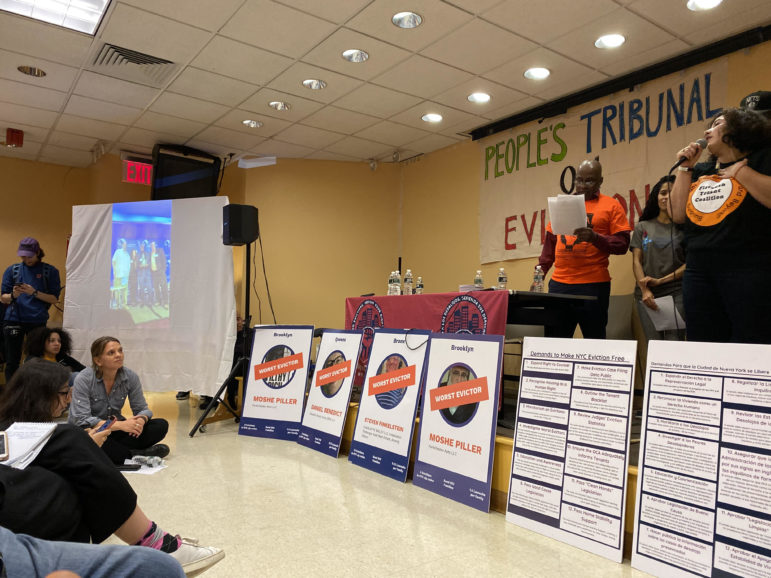

The case for tenants is made at a ‘tribunal’ for landlords who evict.

The witness was named Floriberto Galindo. He spoke through a Spanish interpreter. The defendant was a management company. The crime: a major capital improvement (MCI) at Galindo’s rent-stabilized building in the Bronx.

The MCIs were like an attack towards us,” Galindo, a member of the Northwest Bronx Community & Clergy Coalition (NWBCCC), testified. “They came in and tore things up… and there was dust all over the apartments for over a month … and we were not offered any other place to stay during the construction. We don’t deserve to pay a dollar more. It is enough with the rent we are supposed to be paying.”

MCIs allow landlords to raise rents on stabilized apartments higher than local guidelines would otherwise allow. Galindo said all the documents about his building’s MCI were in English and the repair calculations did not add up; they even confused the tenant’s lawyers.

In a packed room, tenants and housing advocates gathered Tuesday night for a public “tribunal” of landlords they said had violated tenant rights. Dozens of tenants shared stories about leaky ceilings, clogged bathrooms, vermin and mold infestations and landlords asking for cash-only rent payments.

We have neighbors that have been taken to court multiple times without owing any money. We have neighbors who have been intimidated and taken to court because they organize. Others left their homes because they are tired of having to defend themselves in court and live in horrible conditions,” said Judith Rodriguez, a Queens tenant.

The idea of a tribunal came from older civil rights groups, such as the Young Lords or Black Panthers, who would flip the power dynamic by putting agents of the establishment on mock trial for their misdeeds. This week’s version came on the heels of the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition releasing a citywide list of the landlords who evict the highest number of tenants. Both were intended to energize the push for changes in policy—and in agency priorities—to aid tenants.

Doubling down and pushing further

Some of the Coalition’s demands call for aggressive implementation of existing policies, like the continued expansion of the “right to counsel” program—which provides housing-court lawyers to indigent tenants facing eviction—to more ZIP codes and to serve wider income ranges from at or below 200 percent up to 400 percent of the federal poverty line (which is estimated between $20,000 to $80,000 for a family of three). Currently, the eligible income is for households at or below 200 percent of the poverty line, which is an estimated $41, 560 for a family of three. The coalition is also asking for the enforcement of the ban on tenant “blacklists” that was included in last Spring’s renewal of state rent laws.

There are new asks as well. The coalition wants a moratorium on evictions during the colder months of October and May of the year so at-risk tenants are not subjected to homelessness in the winter. They are also demanding an investigation, by the city or by the attorney general, into landlords who are known to file many eviction cases. They propose making more eviction case filing data public, as well. And they want a Housing Court Advisory Council to review the number of evictions by each judge and hold public hearings to obtain feedback from tenants. Also on the list: a “clean hands” bill that would prohibit landlords from beginning eviction cases if they have open housing-code violations against their properties.

Like a broader coalition of housing advocates focused on action in Albany, the Right to Counsel Coalition supports a “good cause” eviction law that would restrict the latitude for evictions across all residential properties, and the Housing Stability Support voucher to fund permanent housing for homeless families.

Susanna Blankley, coordinator for the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition, said these policy targets are part of a broader push to declare housing as a human right—which does not require legal changes but political will.

The most recent eviction data from Open Data NYC shows that between January 1 and October 31 this year there were 14,921 residential evictions (pending or executed). That’s down from 17,544 over the same period in 2018 and 17,939 in 2017.

Landlords: Eviction prevention has already succeeded

The Rent Stabilization Association, the leading landlord group, says those numbers indicate the Right to Counsel is working. Not only is it preventing many evictions outright, it is also delaying others.

“Even if those cases end up with evictions, once a tenant is represented by counsel—which we support—litigation by definition is going to take longer because when both sides are represented by attorneys, there are more issues that lawyers raise that an unrepresented client may not know to raise,” says Mitchell Posilkin, the general counsel for Rent Stabilization Association. “Even if the tenant ends up getting evicted, it’s going to take a lot longer to get there.”

Posilkin said a substantial portion of the rent reform laws passed this June had more to do with changing housing court proceedings and were less about building or creating more affordable housing. He also said the new rent laws have changed the calculus around evictions.

“There is very little incentive for a landlord to want to get a tenant out anymore, because there is no longer a statutory vacancy increase. There is no longer the potential to deregulate a unit. The [Individual Apartment Increase] has been significantly curtailed to the point that is essentially meaningless and irrelevant,” he says.

Regarding landlords who bring many eviction cases, Posilkin said that some landlords own dozens of properties and out of those there might be several tenants who are not paying rent so they would be taken to court. He added that sometimes it takes a court case for the government to step in with rent supplemental programs, such as the One Shot Deal Emergency Assistance program, which helps those households that cannot meet an expense due to an unexpected situation or event, or the Family Homelessness & Eviction Prevention Supplement (FHEPS.) a rent supplement for families with children who receive cash assistance and have been evicted or are facing eviction.

Coalition’s goal is to make evictions truly extraordinary

“No good landlord wants to evict their tenant. By the time you bring the case, then the tenant has a certain amount of time to respond to those papers. Then you get a court date, then you get an adjournment to get your counsel, then you come back to court, then an inspector will go out to the apartment. So every time there is one of those steps, you have to assume it’s anywhere from three to four weeks every time,” says Posilkin. And if, after all that, a judge still issues an eviction order, that means the tenant’s claim could not proven to the courts.

That is not the impression tenant advocates have of how landlords approach evictions.

“Landlords take tenants to housing court for frivolous court proceedings as a form of harassment,” said Carmen Vega-Rivera, tenant leader with Community Action for Safe Apartments (CASA) in the Bronx, in a press release about the tribunal. “Landlords use their power to take tenants to court repeatedly in order to wear them out with the intention of displacing them. This has happened to me numerous times and for many years. Housing court condones this behavior and harassment tactic by slapping the landlord on their wrist and allowing them to continuously bring back the same tenants to court under false pretenses. This practice must stop! Tenants have had enough!”

Blankley says that the only fair chance a tenant facing an eviction has is when they have an attorney on their side and that is why housing court cases are getting extended. Otherwise, a tenant only has 14 days before their eviction order. According to the state court website, if the landlord wins a judgment then the tenant will get a 14-day Notice of Eviction paper from a marshal, sheriff or constable. It gives you 14 days to leave the property and the eviction order can happen even when court dates are missed.

She added those supplemental services Posilkin referred to, such as rent-assistance programs or mental-health services, tend to happen when a tenant has an attorney. Otherwise, a tenant might not know how to navigate the system of rights and resources that are theoretically in place for them.

For the Coalition, the reduced number of evictions represents progress but falls short of the primary goal, which is to impose evictions only in cases where such a dire step is strictly necessary and truly the only resort.

“In a world where everyone has Right to Counsel, the [housing] court is going to look very different,” says Blankley. “We’re trying to expand it so that everybody has it. We really are trying to reframe evictions [which] have become so normalized that we accept them in society and we often focus on the outliers and the very uncommon cases. What we’re saying is that we need to really think about how traumatic they are.”

“Are there other solutions to help that tenant rather than putting them on the street? Do they need supportive housing? Do they need counseling? How could our society look at folks differently rather than saying the solution is to make them homeless?”

Tenants can go to www.worstevictorsnyc.org to see the Worst Evictors List, view the map of evictions, learn about their rights, and connect to lawyers and tenant organizing groups

3 thoughts on “Evictions are Down But Reining in NYC’s ‘Worst Evictors’ is Still on Advocates’ Agenda”

But this wasn’t in the Bronx? We testified in Manhattan..

You are quite right. That was an editing (i.e., my) error, not the reporter’s. We’ve corrected it. Thanks for the note.

I’m a very small landlord and I’m really happy tenants are getting more protections. I own a duplex in queens where I live on 1st floor with my family and tenant lives on 2nd floor. With house prices so high, my situation is very common in NYC because it lessens the burden of a $3500+ monthly mortgage. The bank allows for a bigger loan because they give credit for one unit. In addition to the mortgage, there’s also utilities and occasional maintenance that are bound to come up as we all know. If my tenant was to stop or refuse to pay, it wouldn’t take long before I fall behind on my mortgage and eventually lose my house. TWO FAMILIES OUT ON THE STREET. All because a tenant decided to ABUSE the system. So, my take on this is, for majority of landlords, 2 to 4 unit houses, I hope the lawmakers protect us from our landlords as well… the BANK. I’m sick and tired of landlords being talked about as if we’re all wealthy and in no need or rent money. Just like not all tenants are from HELL, not all landlords are slumlords. And if things get too one sided we’re gonna end up having foreclosures all over, nobody interested in buying multifamily anymore as nobody will want to be a landlord anymore. And the middle class just continuing to leave the city because they can’t afford to buy a house and won’t risk buying duplexes like I did.