Shandra Woworuntu

The author, third from left, argues that better data tracking could stop human traffickers before they harm others as she was harmed.

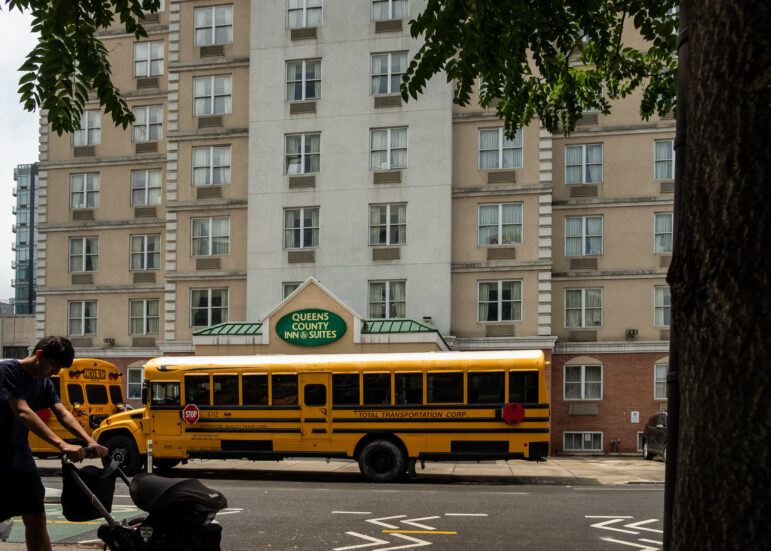

The breadth of testimonies from young women who have come forward to speak out against sexual abuse and rape they suffered under Jeffrey Epstein’s trafficking network comes as no surprise to me. I too was lured to the United States to suddenly find myself sex trafficked in hidden brothels, hotels and massage parlors across the tri-state region.

Nearly 20 years ago in my native Indonesia, I responded to a job advertisement from a recruitment agency promising a seasonal job waitressing in Chicago, with a salary of $5,000 a month. I paid recruiters $3,000 and was provided with proper documentation to obtain a work visa. In June 2001, I flew to New York expecting to work at a hotel as promised. But within a short time, I found myself in captivity, sold repeatedly to numerous sex traffickers.

I was raped and sexually, physically, mentally and verbally abused by my traffickers and sex buyers. I was also recorded to make pornography. The “clients” were very abusive and violent. They felt they owned my body and could do whatever they wanted because they had paid the traffickers, who stole my passport, belongings and demanded that I pay my own ransom of $30,000 for my freedom. Eventually, I escaped and, with the help of the New York Police Department, other women and girls were rescued and some of my traffickers were arrested.

Unfortunately, my experience of being trafficked as an international worker is not uncommon. While much of the reporting surrounding Epstein’s case focuses on the role of prosecutors to bring justice, the work of law enforcement to investigate not only sex but other forms of labor trafficking is severely hindered by the lack of consistent reporting in Congress.

As a member of the U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking, I worked together with people like Ronny Marty, a survivor of labor trafficking. He was recruited for an H-2B housekeeping job in Kansas and borrowed $4,000 to pay his recruiter, purchase airfare from the Dominican Republic and pay visa fees. Ronny never worked in a hotel in Kansas. Instead, he was exploited and trafficked, forced to work in a DVD manufacturing company that paid a very low salary, and charged inflated rent and deductions for many living expenses. Eventually, he escaped and reported the abuse to federal immigration agents who believed his story and helped him access services.

These are just two life stories of foreign workers recruited to work in the United States with false promises were forced to do something else. I founded the organization, Mentari Human Trafficking Survivor Empowerment Program in New York to help other survivors reintegrate into society and live independently. Our organization’s service population is comprised of more than 60% of labor trafficking survivors and most of them came legally to the United States under valid visas.

There is little transparency or data, however, about the non-immigrant visa recipients or types of jobs and employers who rely on temporary worker visa programs. Bipartisan, federal legislation introduced by Sens. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and Ted Cruz (R-Texas), the Visa Transparency Anti-Trafficking Act of 2019, would create a standardized, public reporting system that would help human rights organizations to monitor labor conditions and patterns of employer activity and assist law enforcement investigations aimed at stopping exploitation and trafficking.

Our immigration system is failing to detect traffickers who abuse the system and exploit vulnerable international workers. Had better data been available 20 years ago, I can’t help but imagine and hope law enforcement might have broken up the scheme I survived before I became a victim of human trafficking.

Shandra Woworuntu is a human trafficking survivor and the founder and vice-president of Mentari Human Trafficking Survivor Empowerment Program Inc., a nonprofit that helps survivors of abuse, violence and trafficking reintegrate into society and live independently.