Nicole de Santis

A tree pit grows gross in Brooklyn.

Bushwick does not boast a lot of open space. Nearly 24 percent of its residents live more than a quarter-mile from a park. What parks it has, however, are nicely designed and well used. Take Bushwick Playground, whose 2.8 acres bend around a high school and a row of residential buildings. It offers basketball and volleyball courts, a playground, a leafy seating area and a turf field marked out for baseball where a group of Latino guys often plays soccer during their lunch break, even when the mercury is threatening triple digits.

Some days, Bushwick Playground also offers plenty of garbage. Bottles and wrappers tumble around the turf field. Plastic bags mat onto the fences. In foam takeout containers, leftovers reheat in the summer sun. On three of its last six inspections of Bushwick Playground, the New York City Parks Department has found the site’s cleanliness to be “unacceptable.” According to the advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks, the two City Council districts (34 and 37) that together cover Bushwick have parks that are significantly less clean than parks citywide.

Bushwick’s litter problem is not confined to parks. It boasts a 92.1 percent rate of street cleanliness—which sounds pretty good, except that it ranks sixth worst in the city. The citywide street cleanliness rate in 96 percent and Brooklyn’s is 93.4 percent, according to the Department of City Planning.

Nicole De Santis has a hands-on sense of the litter problem in Bushwick, where she moved 11 years ago. An environmentalist, litter bothers her chiefly because of its ecological impact: garbage washes down storm drains and out to the city’s creeks, rivers, basins and bays, and eventually to the ocean.

When a fellow Bushwick resident posted an announcement for a clean-up project three years ago to, de Santis felt she had to attend, since she’d so often complained about street refuse. She and the organizer were the only ones who showed up for that event. But they decided to try to build a larger effort, and were aided by the sponsorship of a bar and then by an active presence on Instagram. Soon, businesses and residents began contacting what had come to be called Keep Bushwick Beautiful.

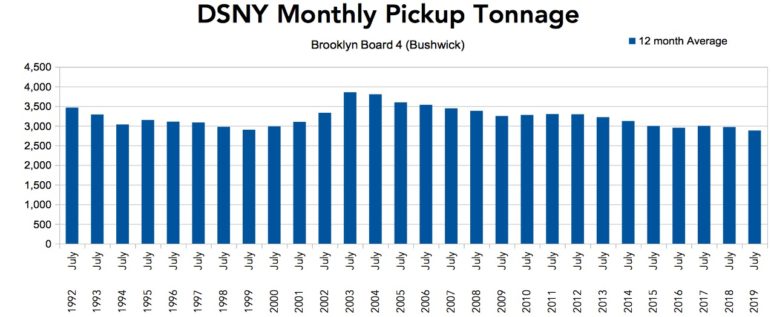

Department of Sanitation (DSNY) statistics indicate that monthly refuse collection in Bushwick has been flat or declining, as is the pattern citywide. But that’s only what gets put in bags and bins. When it comes to tree pits, sidewalks, gutters and playgrounds, De Santis says the trend is clear.

“The amount of garbage has tremendously increased,” since she moved to the neighborhood, De Santis says. “People always want to blame it on the DSNY. It’s true that there aren’t enough garbage cans. But often there is one and it’s empty and there’s garbage all around.” The situation is often worst near the bars, especially around Jefferson Street. “Tons of people come here at night to go to those places. And they just don’t care. It’s gotten much worse.”

De Santis and her partners in the clean-up project aren’t the only ones sounding the alarm about trash. Community Board 4, which covers Bushwick, highlighted the issue in its most recent district statement of needs, a document that boards produce annually to request city investments. “Inconsistent garbage disposal practices and illegal dumping continue to plague the community,” the board wrote.

See where trash cans are located in Bushwick and throughout the city

“Neglected vacant lots full of garbage and abandoned vehicles were historically a major issue in Bushwick and remain an issue, although to a lesser degree today,” the board added. “Presently, there are fewer lots however, garbage and debris from abandoned properties, new construction, and illegal dumping have become a regular and unsightly occurrence.”

The board asked for a resumption of five-day-a-week garbage collection at institutions like schools, pre-K programs and senior centers that “offer daily meals for breakfast & lunch, generating a high volume of garbage.” It also request more enforcement of laws requiring dog owners to properly take dispose of their animal’s waste, and education efforts around new initiatives like curbside organics collection. In the parks, “Additional garbage collection is need to prevent the encouragement of illegal dumping and to keep the park entrances clear/clean.”

Without prompting, De Santis acknowledges that litter is a minor issue compared with the neighborhood’s affordability problems. “If you’re struggling to keep your home, I don’t think street trash is a big issue,” she says. At the risk of oversimplifying a complicated neighborhood, she says, the problem in Bushwick is, “The new people don’t care. The old people are struggling to preserve their homes.”

De Santis says her cleanups attract a mix of Bushwick residents. “I definitely don’t want to be viewed as a gentrifier,” she says. “That’s not my mission.” She teams up for door-to-door outreach with one of the other Keep Bushwick Beautiful organizers who speaks Spanish. Their flyers are being printed in Spanish and English. “We want to reach out because that’s who was here when it as cleaner and its was quieter,” she says.

While trash is not as serious a threat as other challenges facing many Bushwickites, like the potential for eviction or increased immigration enforcement, it is not merely an aesthetic issue. Garbage attracts roaches and rats, whose presence has been linked to the prevalence or severity of asthma, one of Bushwick’s most profound public health problems.

Trash, the community board writes, “impacts the not only the quality of life in the neighborhood, but also general public safety,” because “chronic illegal dumping conditions lead to go-to spots for dumping and also provide breeding grounds for rodents/other small animals.”

The images below were gathered by the Keep Bushwick Beautiful.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

7 thoughts on “Does Gentrification Mean More Garbage, in Bushwick and Beyond?”

Not gentrifiers. Non-gentrified areas have been dirty forever. I have to call 311 daily and its not the gentrification. People just throw trash on the floor especially the homeless

I don’t think it’s the ‘gentrifiers’ who are leaving pizza boxes and empty Corona bottles on the sidewalk. LOL! Looks like a lot of slobs live there. Tell me, was Bushwick pristine in the glorious pre-gentrified days? LOL!

NYC native here. Moved to Central ave in 2015..you’d be surprised at the amount of ‘gentrifiers’ who would hang out in front of all the bars under the J/M line. Constsntly leaving pizza boxes everywhere because they were too busy being drunk and a nuisance to the neighborhood to bother taking their trash with them.

I miss the piles of dog crap, burned out abandoned chopped up cars that were lit on fire and left to melt, the used needles and condoms….. I just want to live in a complete s–t hole. What happened to the packs of wild dogs? No, literally, there were packs of dogs when I moved to this area. Can’t we go back to when people would crap on my front stoop?

Bushwick wasn’t pretty, by an large, pre-gentrification – neither was Park Slope. However, gentrifiers tend to monetize EVERYTHING. Paying absolves the individual from personal responsibility – I watched houses where the owner would sweep in front, efforts supported by “staff” stoop-sitters who would chide litterers, turn into places where the new condo/co-op owners would step over and around trash.

Have faith – eventually the gentrifiers have kids and things change. People realize the crap is no good for kids or property values.

‘…eventually the gentrifiers have kids and things change…’

Should read ‘eventually the gentrifiers have kids and move to a nice house with a 2-car garage in a town with good schools in the suburbs’.

Would love to see a “No Ads” campaign in Bushwick the way they have in Park Slope and other neighborhoods. Half of the trash on my block is from menus, supermarket circulars stuffed in plastic bags, car service and locksmith business cards, etc. Also, I don’t think “gentrifiers” are to blame per se but I do think there is a correlation between economic insecurity and a propensity to litter and generally not give a sh*t about your surroundings. Property owners and people in long term stabilized leases have a sense of pride in their blocks and communities while transients and people who are tripled and quadrupled up in squalid conditions inside their own homes are likely to not care if the sidewalks outside their homes are squalid too and that is true for newcomers as well as long time residents.