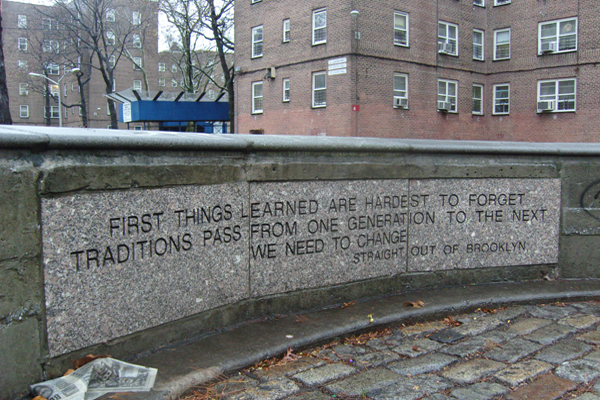

Words of wisdom at the Red Hook Houses, one of more than 300 NYCHA developments that must be operated and maintained on a shrinking budget of federal aid.

Gregory Russ, the appointed chair of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), should be given as warm a welcome as the city can manage. He joins the nation’s largest housing authority during a crucial period of change as it faces a $32 billion capital backlog over the next ten years. To complicate matters, NYCHA is also being overseen by a federal monitor, Bart Schwartz, to bring it into compliance with federal living standards and guide reform of the bureaucracy. Russ must also face a justifiably distrustful resident constituency, fueled by decades of neglect and wary of the privatization Russ spearheaded in Minneapolis and Cambridge. His high salary is controversial, but not surprising—he is taking on a challenge most public housing pros would bypass.

Chair Russ will have to choose his priorities. Here is a suggested starter list:

1. Make Residents an Integral Part of the Planning Process from the Start

NYCHA has already embarked on a major privatization program in its ten-year Plan 2.0 last December. Its PACT program envisions the conversion of 62,000 units—over a third of NYCHA’s housing—to private ownership and management. It is the major source of new capital, $10 to 12 billion, for improving failing infrastructure. In addition, the INFILL program—mixed-income residential construction on NYCHA land—is expected to yield $1 to 2 billion.

The process through which PACT and INFILL program decisions are made needs serious reconsideration. These decisions are made unilaterally by NYCHA. It preselects developments and proposes a plan on which it is determined to move forward, well before residents are engaged. The lead time between engagement and the preparation of a Request for Proposals is short, from 6 months to a year, not enough time to educate resident leaders so they can assess preservation options. At best, residents might change the NYCHA plan at the margins when they meet the selected development team. There is little time to develop consensus.

Resident fears of privatization and gentrification are widespread. The new Chair—already dubbed “the czar of privatization”—may make his mark by democratizing the planning process, along a model innovated in London and the UK.

A timeline of developments considered candidates for preservation should be prepared openly, in coordination with resident leaders. At each candidate development, a joint planning council should be formed—elected residents, community stakeholders, and NYCHA planning staff, with an independent facilitator—to explore preservation options and try to reach consensus on a plan. Approval by a resident majority, using a systematic ballot, should be required before NYCHA can move forward. Elected residents could be offered a seat in the ownership entity to open channels of communication with residents after conversion takes place. This process may take much more time than the rushed RFP process, it may be worth the effort.

2. Strengthen and Streamline NYCHA’s Organization

NYCHA’s organizational structure has been under scrutiny for some time. In 2010, the Boston Consulting Group completed a $10 million study. Recommendations included simplifying its three-tiered bureaucracy—central headquarters, borough management, and over 300 developments—and granting more autonomy to on-site managers. Under the HUD agreement, the federal monitor just commissioned management consultant KPMG to “examine NYCHA’s systems, policies, procedures, and management and personnel structures, and make recommendations.”

There will be a wealth of relevant material relevant to guide potential reform of the bureaucracy. But two areas need immediate attention:

Property Management: Serious lapses—mishandling inspections for toxic lead paint, widespread heating outages during a harsh winter, and chronic problems of accelerating deterioration—have brought NYCHA to this critical point. NYCHA’s ongoing repair program needs to be evaluated, reformed, and accelerated, even in the absence of major capital improvements. Demonstration programs innovated by the previous administration—decentralized management and extended management shifts—should be expanded to all developments. Success on this front may improve the morale of a dispirited management and resident body.

Strengthen NYCHA’s Capacity to Execute Capital Projects: The authority’s reputation is already tarred by the lengthy amount of time it takes to transform capital into tangible improvements, even when it has funding. Next year it stands to receive over a billion dollars for infrastructure improvements—$500 million from the city, $230 million in federal subsidies, and $550 million promised by the state since 2015. Using it effectively will be a crucial test for the authority.

Even when a capital project is completed, residents often complain about the poor quality of work conducted by the outside contractors NYCHA hires. The authority is not effectively monitoring the work done by contractors. This needs to be dealt with as soon as possible.

3. Press for Increased Government Capital Commitments

Even if NYCHA Plan 2.0 succeeds, there will still be a capital gap estimated at $8 billion. The new chair must make the case for increased funding at all government levels.

Russ is in a good position to do that at the federal level, given his experience in the industry. He also needs to make the case to HUD for supplemental funding to support the monitoring agreement, and to Congress for passage of an infrastructure package that includes public housing. (Democrats are pressing for $70 billion for public housing; NYCHA would stand to receive $20 billion.) The city has agreed to $2.5 billion over the next five years, but clearly more is needed. The state may be hardest to deal with—it is unclear how much of its $650 million commitment to NYCHA since 2015 has been allocated. Governor Cuomo promised to release the funds once the federal monitor was appointed. Russ will have to make sure the promise is fulfilled and press the state for more.

In summary, Russ will be at the helm of the NYCHA mothership as it tries to steer a course through uncharted, troubled waters. Concerned New Yorkers should wish him well in charting the future of NYCHA and its residents.

Vic Bach is a senior housing policy analyst at the Community Service Society of New York. CSS is a funder of City Limits.

Opinion: Incoming NYCHA Chairman Should Focus on These Priorities

By Vic Bach.

Words of wisdom at the Red Hook Houses, one of more than 300 NYCHA developments that must be operated and maintained on a shrinking budget of federal aid.

Gregory Russ, the appointed chair of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), should be given as warm a welcome as the city can manage. He joins the nation’s largest housing authority during a crucial period of change as it faces a $32 billion capital backlog over the next ten years. To complicate matters, NYCHA is also being overseen by a federal monitor, Bart Schwartz, to bring it into compliance with federal living standards and guide reform of the bureaucracy. Russ must also face a justifiably distrustful resident constituency, fueled by decades of neglect and wary of the privatization Russ spearheaded in Minneapolis and Cambridge. His high salary is controversial, but not surprising—he is taking on a challenge most public housing pros would bypass.

Chair Russ will have to choose his priorities. Here is a suggested starter list:

1. Make Residents an Integral Part of the Planning Process from the Start

NYCHA has already embarked on a major privatization program in its ten-year Plan 2.0 last December. Its PACT program envisions the conversion of 62,000 units—over a third of NYCHA’s housing—to private ownership and management. It is the major source of new capital, $10 to 12 billion, for improving failing infrastructure. In addition, the INFILL program—mixed-income residential construction on NYCHA land—is expected to yield $1 to 2 billion.

The process through which PACT and INFILL program decisions are made needs serious reconsideration. These decisions are made unilaterally by NYCHA. It preselects developments and proposes a plan on which it is determined to move forward, well before residents are engaged. The lead time between engagement and the preparation of a Request for Proposals is short, from 6 months to a year, not enough time to educate resident leaders so they can assess preservation options. At best, residents might change the NYCHA plan at the margins when they meet the selected development team. There is little time to develop consensus.

Resident fears of privatization and gentrification are widespread. The new Chair—already dubbed “the czar of privatization”—may make his mark by democratizing the planning process, along a model innovated in London and the UK.

A timeline of developments considered candidates for preservation should be prepared openly, in coordination with resident leaders. At each candidate development, a joint planning council should be formed—elected residents, community stakeholders, and NYCHA planning staff, with an independent facilitator—to explore preservation options and try to reach consensus on a plan. Approval by a resident majority, using a systematic ballot, should be required before NYCHA can move forward. Elected residents could be offered a seat in the ownership entity to open channels of communication with residents after conversion takes place. This process may take much more time than the rushed RFP process, it may be worth the effort.

2. Strengthen and Streamline NYCHA’s Organization

NYCHA’s organizational structure has been under scrutiny for some time. In 2010, the Boston Consulting Group completed a $10 million study. Recommendations included simplifying its three-tiered bureaucracy—central headquarters, borough management, and over 300 developments—and granting more autonomy to on-site managers. Under the HUD agreement, the federal monitor just commissioned management consultant KPMG to “examine NYCHA’s systems, policies, procedures, and management and personnel structures, and make recommendations.”

There will be a wealth of relevant material relevant to guide potential reform of the bureaucracy. But two areas need immediate attention:

Property Management: Serious lapses—mishandling inspections for toxic lead paint, widespread heating outages during a harsh winter, and chronic problems of accelerating deterioration—have brought NYCHA to this critical point. NYCHA’s ongoing repair program needs to be evaluated, reformed, and accelerated, even in the absence of major capital improvements. Demonstration programs innovated by the previous administration—decentralized management and extended management shifts—should be expanded to all developments. Success on this front may improve the morale of a dispirited management and resident body.

Strengthen NYCHA’s Capacity to Execute Capital Projects: The authority’s reputation is already tarred by the lengthy amount of time it takes to transform capital into tangible improvements, even when it has funding. Next year it stands to receive over a billion dollars for infrastructure improvements—$500 million from the city, $230 million in federal subsidies, and $550 million promised by the state since 2015. Using it effectively will be a crucial test for the authority.

Even when a capital project is completed, residents often complain about the poor quality of work conducted by the outside contractors NYCHA hires. The authority is not effectively monitoring the work done by contractors. This needs to be dealt with as soon as possible.

3. Press for Increased Government Capital Commitments

Even if NYCHA Plan 2.0 succeeds, there will still be a capital gap estimated at $8 billion. The new chair must make the case for increased funding at all government levels.

Russ is in a good position to do that at the federal level, given his experience in the industry. He also needs to make the case to HUD for supplemental funding to support the monitoring agreement, and to Congress for passage of an infrastructure package that includes public housing. (Democrats are pressing for $70 billion for public housing; NYCHA would stand to receive $20 billion.) The city has agreed to $2.5 billion over the next five years, but clearly more is needed. The state may be hardest to deal with—it is unclear how much of its $650 million commitment to NYCHA since 2015 has been allocated. Governor Cuomo promised to release the funds once the federal monitor was appointed. Russ will have to make sure the promise is fulfilled and press the state for more.

In summary, Russ will be at the helm of the NYCHA mothership as it tries to steer a course through uncharted, troubled waters. Concerned New Yorkers should wish him well in charting the future of NYCHA and its residents.

Vic Bach is a senior housing policy analyst at the Community Service Society of New York. CSS is a funder of City Limits.

Latest articles

¿Qué significa la Ley Laken Riley para los inmigrantes neoyorquinos?

By Daniel Parra

Opinion: Trump is Wrong—Congestion Pricing is Working

By Cody Lyon

Why Is It So Hard To Eradicate Mold at NYCHA?

By Tatyana Turner

Bill Would Make it Easier for Places Outside NYC to Adopt Rent Stabilization

By Jeanmarie Evelly

Opinion: Don’t Let City Charter Changes Silence Your Voice on Land Use

By Graham Ciraulo

more stories:

Opinion: Trump is Wrong—Congestion Pricing is Working

By Cody Lyon

Opinion: Don’t Let City Charter Changes Silence Your Voice on Land Use

By Graham Ciraulo

Opinion: It’s Time For a Late Checkout on NYC’s Airbnb Ban

By Adam Kovacevich

Add Unit