Adi Talwar

The Walton Campus located at 2756 Reservoir Avenue in the Bronx hosts seven schools. The International School for Liberal Arts serves lunch from 9:42 A.M. to 11:30 A.M.

While Ridgewood residents rushed by Grover Cleveland High School on their way to work Thursday morning, several of the students inside were already counting down the minutes until lunch.

Cleveland, a 1,700-student school located in Ridgewood, begins serving the mid-day meal at 9:05 a.m., according to school lunch data in the Office of Food and Nutrition Services’ searchable database. It’s one of at least 100 schools that begin “lunch” before 10 a.m., when many adults are just punching their timecards or scanning their morning emails.

“I heard about that. That’s kind of crazy,” said Brandon, a Cleveland sophomore, as he walked the last four blocks to school a little after 8:30 a.m. Brandon has the opposite problem, he says. His lunch period doesn’t start until 1:38 p.m.

“I don’t eat,” he says. “There’s not even a point. I can just go home and eat.”

His friends Joon, Peter and Jaden also begin lunch late — 12:48 p.m.

“We have gym right before so we’re already really hungry,” Joon says.

They’re not alone. Students at hundreds of New York City schools are heading to the cafeteria at extremely early or late lunch periods, based on a comprehensive review of school lunchtime data by City Limits. Schools generally start classes around 8 a.m. and end around 3 p.m., with some beginning even earlier. First bell rings at Cleveland at 7:42 a.m. most days.

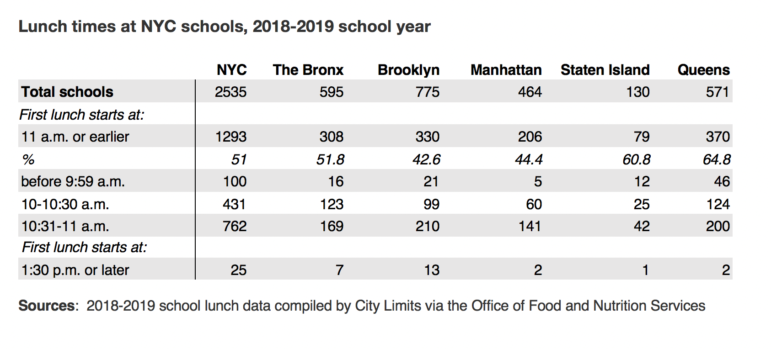

A total of 100 New York City schools (3.9 percent) start serving lunch before 10 a.m. Another 431 schools (17 percent) begin lunch between 10 a.m. and 10:30 a.m., while 762 schools (30 percent) begin lunch between 10:31 and 11 a.m.

In total, students at 51 percent of schools citywide head to the lunchroom at 11:00 a.m. or earlier.

At least 25 other schools begin the first lunch period at 1:30 p.m. or later.

City Limits logged the lunchtime data for all 2,535 schools in the OFNS School Food’s searchable website. The total number of schools includes the roughly 1,800 New York City public schools and 235 charter schools, as well as several Pre-K programs, private religious institutions and Young Adult Borough Center schools for over-aged and under-credited students.

In February, City Limits revisited 2014 lunchtime data published by WNYC and the Daily News and found that 41 of the 75 public schools that began serving lunch before 10 a.m. in 2014 still do five years later. Another 21 still serve before 11 a.m.

This article provides a comprehensive database of lunchtimes at nearly every school in New York City, organized by school name, borough, lunchtime and specific address. The dataset enables readers to consider lunchtime patterns, such as the early lunchtimes at co-located schools, which share the same address, or the preponderance of early lunchtimes at schools in overcrowded districts.

The extreme lunchtimes illustrate the scheduling complications among co-located schools and the consequences of chronic overcrowding, advocates and lawmakers say.

“It’s absurd. As a father, I’ve never called a 9:00 or 9:30 meal ‘lunch,'” says Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. “I don’t think any parent has done that, so why are we treating our students like that?”

“It’s beyond outrageous,” he added.

Just over 51.8 percent of schools (308 of 595) in the Bronx start lunch at 11 a.m. or earlier. About 42.6 percent in Brooklyn (330 of 775), 44.4 percent (206 of 464) in Manhattan and about 60.8 percent (79 of 130) in Staten Island at 11 a.m. or earlier.

But nowhere is the lunchtime situation worse than in Queens, where 64.8 percent of schools (370 of 571) begin lunch at 11 a.m. or earlier.

Adi Talwar

M.S. 280 in the Bronx servers lunch to its students from 9:55 A.M. to 12:10 P.M.

Crowded schools, extreme lunchtimes

As the four friends from Grover Cleveland High School in Ridgewood can attest, Queens has some serious school lunch time issues. Their school is located in District 24, one of the most overcrowded in the city.

There are 45 other schools in Queens that begin serving lunch before 10 a.m.

Councilmember Mark Treyger, chair of the Council’s Committee on Education and a former Brooklyn high school teacher, attributes the pattern of extreme lunchtimes to significant overcrowding in Queens schools.

“Queens has some of the most serious overcrowding in our system,” says Treyger, who represents part of South Brooklyn. “It’s a very, very big issue.”

A 2018 City Council report found that Queens schools have the highest average “utilization rate” — the Department of Education’s term for capacity and overcrowding — of any of the five boroughs, at 108 percent.

District 25, which includes College Point, Whitestone and Flushing; and District 26 — Oakland Gardens, Fresh Meadows, Bayside and Auburndale — are both at 121 percent capacity, according to the report. District 24 — Corona, Lefrak City, Elmhurst, Maspeth and part of Ridgewood and Glendale — is at 115 percent capacity.

Francis Lewis High School in Fresh Meadows — located in District 26 — is at 200 percent capacity, according to the School Construction Authority. The school begins serving lunch at 9:32 a.m. and the cafeteria finally closes after the last shift of students at 2:04 p.m.

The school recently broke ground on a new 555-seat annex to alleviate the crowded classrooms, but it is unclear how that will affect lunchroom usage.

John Bowne High School, in District 25, serves lunch from 9:30 a.m. to 2:27 p.m. Benjamin Cardozo High School, in District 26, serves lunch from 9:37 a.m. to 2:15 p.m.

A December 2018 report by the organization Class Size Matters determined that New York City public schools “are critically overcrowded.” Roughly 575,000 students — more than half of the city’s total — attending schools that are at or above 100 percent capacity, according to the DOE’s most recent data from the 2016-2017 school year.

About 43 percent of all schools, including 60 percent of elementary schools, were at or above capacity, Class Size Matters reported.

Adi Talwar

P469X, the Bronx School for Continuous Learners, serves lunch to students during the normal range: 12:00 P.M. to 12:40 P.M.

Co-location compromises and consequences

The city closed Walton High School in Kingsbridge in 2008, amid an effort to shutter large “low-performing” schools and open various smaller schools in the same building. The building formerly known as Walton High at 2756 Reservoir Ave. now hosts seven schools.

As with co-located schools across the city, the new arrangement necessitates compromise among the different principals whose students all depend on the same cafeteria, gym and classrooms.

The International School for Liberal Arts begins serving lunch at 9:42 a.m. and ends at 11:30 a.m. Two hours later, its the High School for Teaching and the Profession’s turn. Their students are served in shifts from 1:57 p.m. to 2:42 p.m.

The four schools inside the old Jamaica High School, which closed in 2014, face the same dilemma.

“[Early lunches are] not the particular case for my school, which shares the Jamaica Campus with three other schools, but it is very common and a terrible problem,” High School for Community Leadership Principal Carlos Borrero told City Limits in February. “In our case … we are extremely lucky.”

Jamaica Gateway to the Sciences is not. They begin serving lunch at 9:06 a.m. and the last shift ends at 2:09 p.m.

“There complaints from co-located schools and campuses are that they’re forced to make choices about who goes first and who goes next,” Treyger says. “Let’s not treat each school in silo.”

“Maybe more than one school can share space. Maybe multiple schools can find way to share the cafeteria,” he adds.

Social, emotional and physical health consequences

Early lunchtimes leave students starving at the end of the day. Students told City Limits in February that they typically head to the bodega or vending machine for a quick fix when the last bell rings.

A lack of food throughout the day aggravates the normal hunger that kids experience during their teenage growth spurts, says journalist Andrea Strong, founder of the parent-led advocacy group The NYC Healthy School Food Alliance. After school, they’re more likely to fill up on honey buns and candy bars because they crave food quickly.

“The link between food and learning is really strong and children need to eat whole, nutrient-dense foods for lunch,” Strong told City Limits in February. “It leads to obesity when kids leave school hungry. They go for what’s easy and think, ‘I need snacks, I need snacks.’ So they get a candy bar because it’s quick to fill you up.”

Liz Accles, executive director of Community Food Advocates, says the issue is about “educational equity” because it has a disproportionate impact on low-income students who may depend on school food for their only meals of the day.

“Lunch is as integral to their educational wellbeing as their time in the classroom,” Accles says. “For kids who don’t have many other options for their meals throughout the day, it’s that much more essential.”

A total of 114,569 New York City students — one in 10 kids — were identified as homeless during the last school year, Advocates for Children of New York reported in October 2018. Accles says appropriately spaced nutrition affects school performance, mood and life outside school — especially for the tens of thousands of children who are unstably housed.

“Kids whose families are struggling financially and really rely on the meals, how are they getting through the day?” she says.

Adi Talwar

Back at the Walton Campus, the High School for Teaching and the Profession’s serves their students lunch from 1:57 P.M. to 2:42 P.M.

Demanding a ‘message from the top’

The February City Limits story about extreme school lunchtimes, as well as a similar March report by the Daily News, prompted responses from Mayor Bill de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza and even made it into

“That has to change. It’s unacceptable,” de Blasio said at a March press conference reported by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “I am a parent, and I can say parents don’t want to see that for their kids.”

“Lunch should be lunch,” Carranza added.

“That being said, there are a lot of moving parts, especially in schools where you have a lot of co-located schools,” he said.

As this school year comes to an end, it remains unclear what action the DOE and OFNS will take before school resumes on Sept. 5

Department of Education spokesperson Miranda Barbot rephrased a statement that DOE gave City Limits in February.

“Students shouldn’t eat lunch before 11am, and we’re working with each school serving lunch before that time to make adjustments if possible for the 2019-20 school year,” Barbot says. “We provide free, healthy breakfast and lunch for all students, and work with schools serving an early lunch to offer students food later in the day.”

The DOE did not respond to questions about how the crowded or co-located schools will adjust their schedules. OFNS now reports directly to the DOE.

Treyger says the problem of extreme lunchtime demands creative solutions, as well as a clear commitment from Carranza that appropriate lunch times are a priority.

“We need a message from the top that reaches the superintendents, reaches schools and that says, ‘This is how you can ensure that schools will have lunch at a reasonable hour,'” Treyger says. “There are creative ways to address this, but you need a message from the top.”

He used to teach at New Utrecht High School in Brooklyn — which starts serving lunch at 9:04 a.m. — and said the school was able to accomodate teachers’ demands for longer prep periods by shortening some classes.

“We found creative ways to create planning time,” he says. “There are ways to adjust periods in a school day.”

Treyger says the Council should begin requiring the DOE to report on lunchtimes and schools’ progress toward ensuring appropriate meal times.

Accles, of the Community Food Advocates, also called on Carranza and DOE leadership to prioritize “harmful” lunch times.

“It’s a systemic problem and it needs a systemic answer,” Accles says. “It directly impacts how kids experience the school day, and how everyone else in the school experiences them

CityPlate, City Limits’ series on food policy, is supported by the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund. City Limits is solely responsible for the content.

One thought on “See Which NYC Schools Eat Lunch Before 10 a.m.”

Pingback: Rise & Shine: Advocates press de Blasio to reduce class sizes – AbZorb