Charles Edward Russell

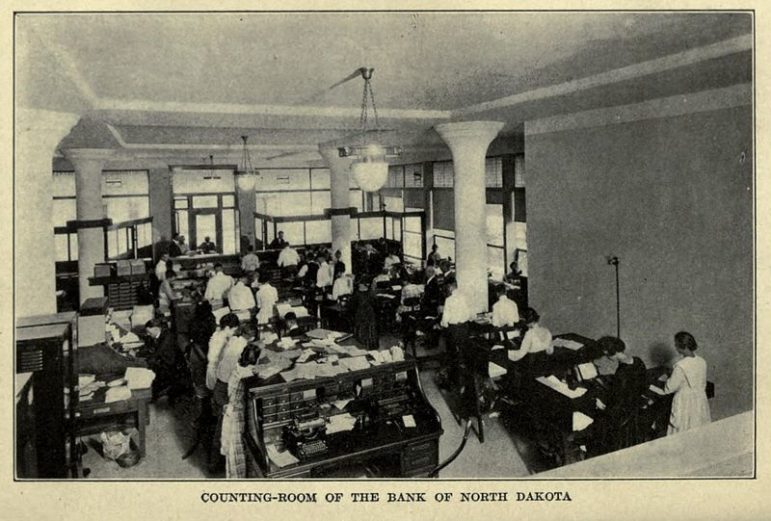

The counting room of the Bank of North Dakota, circa 1920. It remains the only public bank in the United States.

A coalition has begun calling for a municipal public bank in New York City. While the issue has attracted modest attention or support so far locally, it has gained some traction in other U.S. states. Here’s what you need to know about it:

What is a public bank?

A public bank is a bank in which a state, municipality or other public entity is the owner, unlike a private bank, where the owners are usually private shareholders. Current major public banking models include the Bank of North Dakota and the German Public Bank System as well as many nations postal bank systems.

What is the historical context of public banks?

They proliferated globally in the early 20th century as part of industrialization in both capitalist and socialist countries. The only public bank that exists in the United States now is the Bank of North Dakota. Formed by revolutionary populists in the 19th century, the bank still plays an integral role in the state’s agricultural economic development.

Where are public banks under consideration now?

State lawmakers in California, Oregon and Illinois are considering bills advocating for the establishment of public banks, and those proposals appear to have considerable support.

What’s different about a public bank?

Because they do not serve shareholders, public banks can use their financial power to further the public interest. Proponents say a public bank wouldn’t charge fees solely to generate profits, and would refrain from investing its deposits in industries like fossil fuels, instead harnessing its financial strength to build infrastructure and offer banking services more widely.

Are banks really a city issue?

Federal and state regulators oversee private banks, so the city has no power as a regulator. But public-bank proponents say the city wields power as a depositor and an investor – it deposits billions in tax revenue into banks before spending it, and it controls multibillion-dollar pension funds. Some of that money could instead capitalize a public bank.

What’s in it for the city?

Proponents of public banks say the city could save on fees and better leverage its savings to pursue its broader policy goals (for economic development, environmental protection and more) if it banked through a public mechanism.

What are the possible downsides of a public bank?

Starting and running a public bank would require some amount of public spending. A public bank’s lending decisions could be dominated by political considerations, causing the bank to make bad bets with poor financial outcomes. Or there could be outright corrupt decision-making—though private banks are not immune from either problem. Extracting the city from long-standing relationships with private banks could be messy, and possibly involve litigation.

Who is pushing for it here?

Groups like the New Economy Project, Chhaya CDC, the Public Bank NYC coalition, and Freedom to Thrive.

Where does the campaign stand?

It’s in its early stages of building a coalition, with an emphasis on community-based and constituent-led organizations for leadership. Because of the nature of the fundamental shift this would present, the proponents expect a multi-year campaign.