This is a pivotal time for the future of the rental housing market in New York City; the state’s rent stabilization law, which protects about a million households, comes up for renewal in a little over a month.

There are a currently nine bills in the Senate and the Assembly which will not only close the destructive loopholes that have been eroding the rent stabilization system for the last 25 years, but also expand protections to up to 600,000 unregulated tenant households in New York City that are vulnerable to unjust evictions. If the legislature fails to take action on these bills, the city I love will continue to slip away.

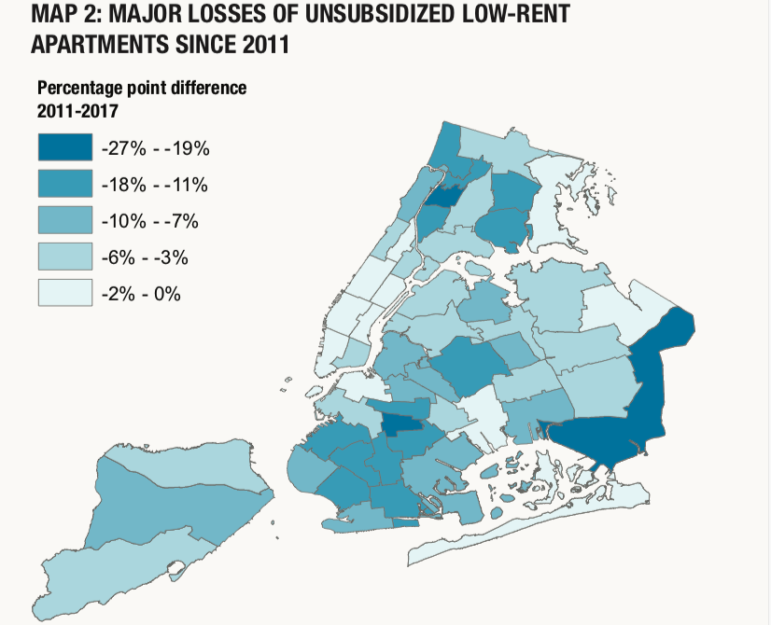

New York is rapidly losing its low-rent apartments, creating a housing market where many tenants are squeezed between a rock and a hard place: severe rent burdens at home and no affordable alternatives on the market. In our newly released report, Where Have all the Affordable Rentals Gone? we found that city-wide, the share of unassisted low-rent apartments (those with rents of approximately $900 in 2011 and $990 in 2017) fell from 21 percent to 14 percent between 2011 and 2017, from 445,000 to 300,000 units.

Major losses in low-rent apartments in NYC

Low-rent apartments are disappearing because of the loss of unregulated low-rent units in low-density neighborhoods of Queens, Staten Island, and outer Brooklyn. Unregulated tenants do not have a right to a lease renewal. If a landlord wants to hike up the rent or to kick the tenant out as reprisal for asking for repairs, they can.

The loss of low-rent units is also driven by the destructive impact of rent law loopholes–vacancy bonuses, Major Capital Improvements (MCI), Individual Apartment Improvements (IAIs), preferential rents, and vacancy decontrol–on rental submarkets in the Bronx, upper Manhattan, and central Brooklyn. While they may seem like reasonable provisions for ensuring the maintenance of the city’s housing stock, these loopholes all work in tandem to push out low-income tenants and undermine neighborhood-level stability.

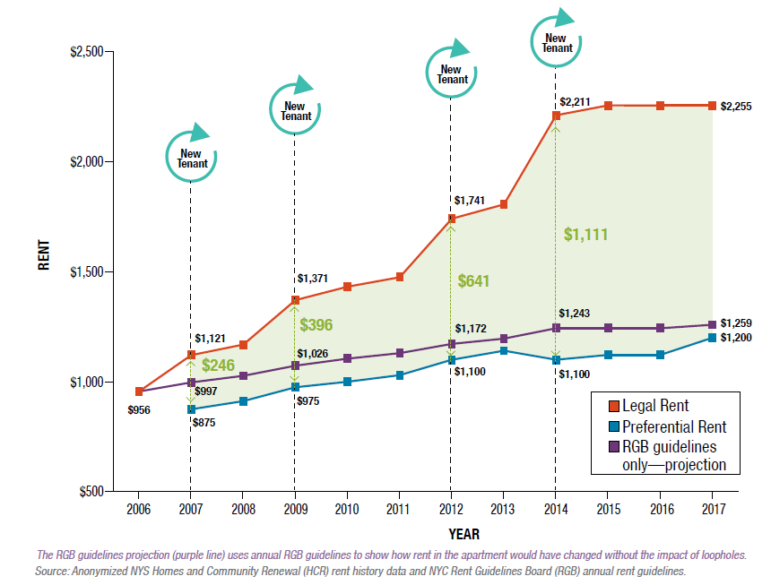

Rent law loopholes work in tandem

Here’s an example: the chart above shows a real rental history for a one-bedroom apartment in Pelham Parkway in the Bronx. It illustrates how vacancy bonuses and preferential rents work together to functionally destroy renter protections. Since 2007, the landlord was able to claim four vacancy bonuses in a row, creating a $1,111 gap between the preferential and legal rent. Because the preferential rent is revocable, the tenant is effectively not protected by rent stabilization laws. If the landlord decides they want the tenant out, they can hike the rent by $1,111 when the lease is up (see more rental histories in CSS’s new report, Closing the Loopholes: What six rental histories tell us about fixing rent regulation).

Where the share of high-rent apartments grew

At the same time, New York City’s high-priced rental market is expanding from the Manhattan core, Northern Brooklyn, and Northwestern Queens further into the outer boroughs. The share of high-rent units (more than $2260 in 2011 and $2470 in 2017) grew from 8 percent to 13 percent between 2011 and 2017, increasing from 170,000 to 280,000 units.

The end result of the loss of low-rent units and the focus on high-rent unit production is a rental market heavily skewed toward high-income earners. High-end vacancy was nine percent in 2017, while low-rent vacancy was under two percent.

The production of high-rent units does not ease the pressure on the low-rent submarket, because of housing market segmentation. If rents in Long Island City’s or Chelsea’s new towers drop because there are too many ultra-luxury rentals, there may be a leveling impact on the adjacent rental submarket of slightly cheaper, but still high-rent units across the city. However, this impact will not filter down to a moderate or low-rent apartment in Kingsbridge or on an unregulated basement apartment in Queens Village.

The nine bills in the Assembly and Senate are a step toward mitigating the loss of low-rent units and the ubiquitous sense of housing insecurity among low-income New Yorkers in the city and beyond.

Oksana Mironova is a housing policy analyst for the Community Service Society.

CSS is a former owner of and currently provides some funding to City Limits.

5 thoughts on “Opinion: Why NYC is Rapidly Losing Low-Rent Apartments”

New 2-family homes on S.I. have asking prices in the $1M range. So the rental units in homes like that are going to be asking for around $2200/month rent for a 3BR apartment. Resale 2-family homes are now going for the high $800s, same situation with the rental unit there, maybe around $1900/month for a 3BR based on my own neighborhood. There are only about 900 3-family homes on S.I. and they tend to be in the older run down parts of the island.

SI 1,2 & 3 family homes:

3-FAMILY 888

2-FAMILY 29961

1-FAMILY 77052

Why was there no mention of the impact of increasing property taxes and accelerated housing acquisition costs on rental costs?

And the cost of everything else going up.

But of course rent is only supposed to go up 1% or 0% every year while infation, property taxes, water/electric/gas bills and maintenance cost rises.

The city politicians and lazy renters want private landlords to subsidize and theoratically be charities so everyone has somewhere cheap to live regardless of circumstances. Honestly, mind blowing.

FYI, here’s a breakdown of all 1, 2 and 3-family homes by borough:

Bronx 1-FAMILY 21868

Bronx 2-FAMILY 29638

Bronx 3+FAMILY 11322

Brooklyn 1-FAMILY 61000

Brooklyn 2-FAMILY 95058

Brooklyn 3+FAMILY 35362

Manhattan 1-FAMILY 2207

Manhattan 2-FAMILY 1838

Manhattan 3+FAMILY 1467

Queens 1-FAMILY 152727

Queens 2-FAMILY 93627

Queens 3+FAMILY 24028

Staten Island 1-FAMILY 77052

Staten Island 2-FAMILY 29961

Staten Island 3+FAMILY 888

NYC total = 638043

Everything in this article has to do with laws. Laws can’t help you, the entire rest of the united states is almost completely unregulated and yet their rents are rock-bottom in comparison to NYC ($1000/2br, $1200-$1300/3br, etc, in most the US). The fact is the city government has more fun trying to ‘fake’ low rent prices but not actually allowing supply to meet demand. There is literally just not enough houses to provide for all of the people who want to live here. No one will ever accept being homeless, so rents will go astronomically high until you just give up and move out, which is really hard because all of the jobs are here. NYC needs to fix this office : residential ratio, no one can live here without a job. So if you want to fix the housing crisis, turn office space into residential space. Rent will drop like a rock, the landlords will be unable to fill their vacancies because no one can live here without getting a job.