Sadef Ali Kully

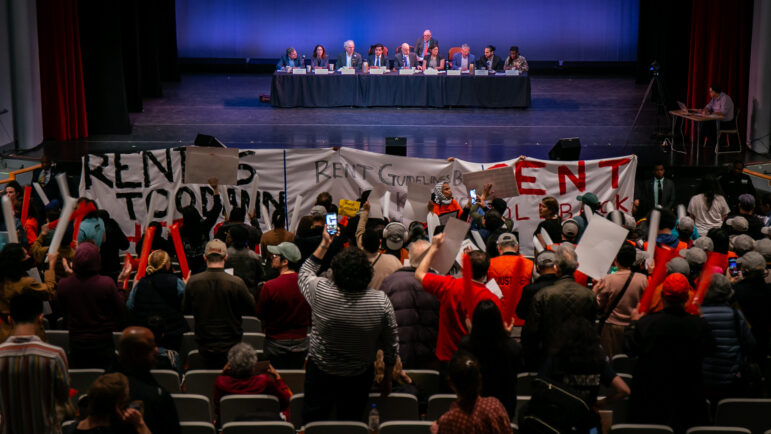

Members of the coalition supporting the inclusion of racial-impact assessment in the environmental review process, including State Sen. Julia Salazar (at far right) and Assemblywoman Maritza Davila (in grey coat) rally on Sunday.

Bushwick resident and Community Board 4 chairman Robert Camacho has watched long-time neighbors disappear and local businesses close up shop in his neighborhood while new residential developments with market-rate housing units have gone up. That’s why he wants the city’s environmental impact process to include an analysis of the impact of land-use changes on racial groups.

“People I have known for years are gone. My grandmother who lived here most of her life would not recognize this place. We do need an impact study but the people living here already know what the study is going to show, because our people are no longer there. Our people are being pushed out,” said Camacho.

Churches United for Fair Housing (CUFFH) was joined by community leaders and elected officials Sunday outside of St. John the Evangelist Church across from NYCHA’s Williamsburg Houses in a call for the city to include a racial impact study component in the environmental review the city conducts before neighborhood rezonings. This would require the city to change the text amendment in the technical guide for the City Environmental Quality Review.

CUFFH said the history of rezonings, especially the 2005 Williamsburg waterfront rezoning, which have led to increased harassment, evictions, displacement and ultimately, racial segregation, illustrates why it is vital for the city to acknowledge the problem and take the right steps to solve the problem, “[The mayor] can do this with a swipe of a pen,” said Alex Fennell, CUFFH Network Director.

For CUFFH, concern about the racial impact of land-use actions goes back at least a decade. The Broadway Triangle case was a fight between the Bloomberg administration and the community in 2009. The city had proposed to rezone 31-acre triangular industrial site between Union and Flushing Avenues bounded by Broadway for the development of hundreds of affordable housing units. The area was heavily segregated: Latino, Blacks and the Hasidic community each had their own neighborhood blocks.

The Broadway Triangle Community Coalition said the city’s method to choose who qualified for the affordable housing units would have given a preference to the Hasidic community. A lawsuit halted the development. Later on, the de Blasio administration in conjunction with the coalition came to an agreement to have 375 affordable apartments set aside for a larger swath of low-income Broadway Triangle residents.

“The city failed to meet the Fair Housing Act obligations,” Fennell said of the Broadway Triangle episode. “The city is still failing. We want the racial impact study [provision] to be included in all new rezonings.”

The environmental impact study (EIS) is supposed to identify any potential adverse environmental effects from proposed actions, assess their significance, and propose measures to eliminate or mitigate significant impacts, according to the Department of City Planning.

State Assemblymember Maritza Davila, who said her office has been inundated daily with people who are being displaced in their communities, wonders why an EIS that explores so many facets of a neighborhood—its workforce, open space, traffic, housing market and even shadows—cannot also look at racial impacts.”We can monitor the environment, we can monitor the pipes that go down the street, but who’s monitoring us? No one. It’s an injustice I believe can be dealt with through the racial impact study. We need to study people, not buildings.”

State Senator Julia Salazar linked the fight in Albany for fairer rent laws, which are set to expire in June, with the push for a racial impact-study mandate as part of a fairer housing plan for New Yorkers.

“While we have a responsibility as state legislators to fight for stronger rent laws this year — that finally work for tenants instead of landlords and developers — we also have a responsibility to fight for accountability in the zoning process. A racial impact study in the rezoning process is a critical way for us to hold the city accountable for the impact we know is happening to our communities,” said Salazar

At Sunday’s announcement, residents, including teenagers, told stories of how their neighborhoods have changed and wondered whether they would recognize the places they grew up 10 or 20 years from now. Emely Rodriguez, a CUFFH youth leader, said she has watched her family-owned dry-cleaners go out of business. Camacho said if the city needed proof that neighborhoods were changing in dramatic ways, they just had to come to Bushwick: “Tell them to come see me and I will show them around.”

Advocates say Bushwick has been shaped by the ripple effects from rezonings elsewhere in Brooklyn. According to the Furman Center, the median rent in Community District 4 shot from $1,600 in 2010 to $2,600 in 2016 (before easing slightly to $2,530 in 2017). During that 2010-2016 period, the area’s Black population share fell by a fifth and its Latino population share by more than 10 percent; the White share nearly quintupled from 3.1 percent to 14.8 percent.

The city has chosen Bushwick for a neighborhood rezoning as part of the de Blasio administration housing plan slated to create and preserve an estimated 300,000 housing units across the city. The administration has released a draft rezoning framework. The next step would be for the city to present its plan, followed by community engagement meetings before a final neighborhood plan is released from the city and then a draft environmental impact statement is prepared.

Hoping to avoid mistakes like the Bloomberg-era rezoning of Williamsburg, councilmembers Antonio Reynoso and Rafael Espinal in 2014 launched a community planning process for the rezoning of the Bushwick area. The Bushwick Steering Committee for the rezoning, with over 200 members from Bushwick residents to community organizations, released its own plan in September.

Pastor Jason Taber from St. John the Evangelist Church said he had seen his congregation disappear over the last decade and the impact was lasting on those left behind. “We have seen 50 percent of our congregation forced out. As a city, as a community we can do better.”

Councilmember and Public Advocate candidate Jumaane Williams said the impact if displacement for communities of color was one of the reasons why he voted against the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program in 2016 and the rezonings the de Blasio administration had announced in 2014.

“I am disgusted to even have to be here but we have to be here. I want to disavow some of the people who say, ‘They are always playing the race card.’ Don’t do that—don’t diminish the experiences of people with more melanin in their skin. What is happening with all the rezonings is that the Black and Latino communities are getting the short end of the stick,” said Williams.

According to Race Forward, the Center for Racial Justice Innovation, a racial impact study could take a look at several factors such as identifying and engaging racial/ethnic groups being adversely affected in the area, gathering quantitative and qualitative evidence of inequality, mapping potential impacts of the land-use action and determining ways to measure what actually transpires.

“We need to know how each rezoning will affect our communities, five, 10, 20 years down the road,” said Julio Salazar from Congresswoman Nydia’s Velazquez office.