Murphy

Stringer unveils his call for a different housing plan.

Saying Mayor de Blasio’s massive housing strategy has failed to address the city’s accelerating affordable crisis, Comptroller Scott Stringer on Thursday proposed a dramatic shift of the plan toward lower-income families—including the homeless—and called for reform of real-estate taxes to pay for it.

“We have not shifted the housing plan to where the greatest need is and that’s for the people who are the backbone of our city,” Stringer said, pointing to a population of 580,000 living in households that either pay more than half their income in rent, live in severely overcrowded conditions or have recently been in a homeless shelter.

“We need a new approach,” he said, adding that his plan “could be what Stuy-Town and Mitchell-Lama meant to the city decades ago.”

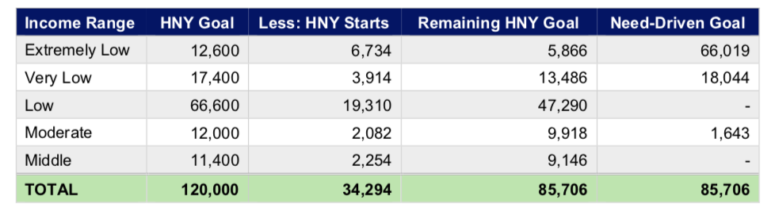

Stringer’s plan would shift the remaining 85,000 units of new construction under the mayor’s plan to serve very low-income and extremely low-income families, and require that 15 percent of all units built in each year be reserved for people leaving homeless shelters.

The cost of $375 million in annual capital money and $125 million a year in operating subsidies to maintain the housing that is created. Stringer’s plan calls for raising the Real Property Transfer Tax rate on high-home sales to generate the needed funds.

While the headlines about the plan will focus on this shift of new construction to lower-income people, the move to include new operating subsidies is also significant, since supporting low rents over time typically requires Section 8 vouchers, which are not limitless in supply. David Jones, president and CEO of the Community Service Society (a City Limits funder), said the Stringer proposal was significant for being the “first serious proposal recognizing the importance of operating subsidies in affordable housing.”

Stringer’s plan would not affect units of housing that are being preserved rather than built anew, which represent the majority of homes covered by the mayor’s plan.

Need versus delivery

In a report issued Thursday, Stringer’s office said the city had added half a million residents since 2009 but only 100,000 new housing units, leading to a rise of average rents by 24 percent. The need is most acute among about 515,000 households that are either rent burdened, overcrowded or have spent time in a shelter and have incomes considered “very low” (less than $46,950 income for a family of three) or “extremely low” (less than $28,170 for a family of three)

Critics have long faulted de Blasio’s Housing New York plan, which was launched as a 200,000-unit, 10-year plan in 2014 and expanded in 2017 to a dozen years and 300,000 units, for targeting moderate- and middle-income families even though statistics illustrate that housing need is most acute for the poorest New Yorkers.

“For decades the city has had the same housing – from Giuliani to Bloomberg to de Blasio. The only thing that changed was the number of units that they built. Every single time, the plans paid no attention to the actual needs of the people of New York City,” said Jonathan Westin, the executive director of New York Communities for Change. “Those plans have all failed.”

While de Blasio did shift the plan in late 2016 to devote a slightly larger share of apartments to lower-income groups, City Hall has defended its general approach of subsidizing apartments for families making as much as $160,000 a year. De Blasio has said there is need up and down the income ladder that the city must address. And housing officials have noted that serving lower-income families, who require larger subsidies, would mean building or preserving fewer units within the plan’s multibillion-dollar budget.

Stringer’s critique dismisses the first point—he gave the mayor credit for putting forward the most ambitious initiative since Mayor Koch’s 10-year plan, but said “the current plan is simply out of line with where we need to build.” He presents an alternative to the second: a new source of revenue that would have the added benefit of correcting inequity within the existing tax system.

Streamlining taxes, Raising revenue

The Stringer proposal calls for a massive increase in the cost of the mayor’s plan—a boost of 60 percent over its remaining years. He wants to pay for this by raising the Real Property Transfer Tax rate on higher-value home purchases. The RPTT is applied to all home purchases.

Office of the Comptroller

The mayor's plan(left) and the proposed Stringer revision (right column).

Stringer also wants to eliminate a second tax, the Mortgage Recording Tax, which only affects purchasers who borrow the money to buy a property. That means richer buyers, who pay cash, don’t pay it. The comptroller reports that in 2016, 90 percent of Manhattan townhouses that changed hands sold for cash.

“This system is patently unfair,” Stringer said. “It’s a penalty on the middle class.”

By eliminating the MRT and making the RPTT more progressive, people buying homes valued at less than $500,000 with a mortgage will go from paying 2.9 percent to 3.2 percent under the current system to 1 percent. Those buying a home valued at $10 million in cash will go from paying 2.8 percent to 8 percent.

Asked whether this new housing revenue source ought to support the beleaguered housing authority instead of new construction, Stringer said new affordable housing was needed to address the tens of thousands on NYCHA’s waiting list. “We have to be able to deal with the affordable housing crisis om multiple fronts,” he said.

The tax changes would require Albany’s assent, something Stringer said would be facilitated by the Democratic takeover of the State Senate in January.

Changing the focus of the mayor’s housing plan would almost certainly require the mayor’s cooperation, something Stringer said he would work to achieve. “We’re going to launch the biggest campaign on this proposal that we’ve every seen,” he said. “The progressive city is just failing the poorest people in the city. I believe we can sell this plan to City Hall.”

Mayor spokesman Jane Meyer told City Limits in a statement: “Our city is in the grips of an affordability crisis, and the mayor is confronting it head on. From creating affordable housing at record levels, to rent freezes and free lawyers for tenants facing eviction, this administration is fighting this crisis with every available tool – not just the housing plan being looked at by the comptroller.”

One thought on “Comptroller Says Housing Plan is Failing, Calls for More Units for Low-Income NYers”

Even with Stringer’s plan this is a bottomless pit that will lead the city into insolvency. Give it up.