Office of the State Comptroller

Tom DiNapoli, the Democratic incumbent running for re-election as state comptroller, has staked out a position as an advocate for environmental standards in how the pension fund invests. But he has stopped well short of supporting divestment from fossil-fuel stocks.

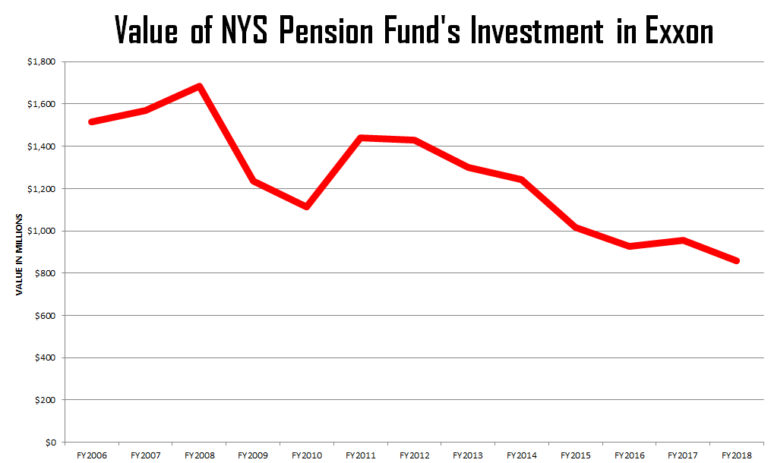

Over the past dozen years, as warnings about climate change have become more dire and dozens of institutional investors have shunned stocks associated with the fossil fuel industry, New York State’s public-employee pension fund has shed more than half a billion dollars of its holdings in ExxonMobil.

But as of July, ExxonMobil was still the 10th largest investment in the $209 billion Common Retirement Fund overseen by state Comptroller Tom DiNapoli, with New York controlling more than 11 million shares of Exxon stock, a stake worth close to $900 million.

Exxon also figured prominently in the comptroller’s most recent rundown of annual “shareholder activism”—the efforts the fund makes to force change at the companies in which it has an ownership stake. The highlight of that work in 2017 was a 62.3 percent vote among Exxon shareholders at their May meeting on a motion related to climate change that was sponsored by the New York State pension funds and the Church of England. Exxon eventually agreed to abide by the resolution. It was hailed as a victory for DiNapoli.

The motion didn’t call for Exxon to change its business, however. It didn’t stop one barrel of oil from coming out of the ground or one gallon of gas from flowing into a fuel tank. It merely required a report on how climate change risks might affect Exxon’s business.

The saga of its dealings with Exxon embodies the tensions inherent in the job of comptroller, to which DiNapoli is seeking a third full term in the November 6 election. As custodian of one of the largest pension funds in the country, the comptroller wields enormous financial power, and must choose how to wield it.

Does he merely pursue the largest possible return on investments, to ensure retirees get paid without putting taxpayers on the hook? Or does he align the pension investments with broader public-policy principles, to make sure the state isn’t creating problems with one hand that it will have to solve with another?

An example of the latter came recently. Just last week, the state attorney general sued Exxon. Her allegation was that Exxon had, by failing to truthfully report the impact of climate change on its business outlook, defrauded investors—including the New York State pension fund.

Sell, baby, sell

The scale and impact of the state’s $208 billion pension fund is hard to overstate. Most of its 471,000 retirees are located in New York State, where the $9.8 billion paid out last year is a significant economic force. But the fund has a still broader footprint: Last year, it paid just shy of a billion dollars to Florida residents and sent more than $100 million each into the states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and South Carolina. Twenty beneficiaries of the state pension fund spent their money in Alaska. Two people in Guam received pension checks from DiNapoli’s office.

The fund combines stocks in some 4,700 individual firms with holdings of bonds, mortgages, real-estate and hedge-fund investments. Its fossil-fuel industry dealings go well beyond Exxon—from its $600 million stake in Chevron to the $6,601 of holdings in the Westmoreland Coal Company. Both foreign and domestic firms are in that mix. Some sell fossil fuel, others explore for it, and a few drill it out of the ground.

In a statement released after Attorney General Barbara Underwood announced her suit against Exxon, Green Party candidate Mark Dunlea contended, “Until the pension fund divests, our state is in the odd position of investing in the same business it is suing for fraud. This defies logic and is an absurd investment strategy.”

Well behind in fundraising and the polls, Dunlea is unlikely to make much of a dent in the race for comptroller. But he expresses a growing sentiment on the left about how the state should behave as an investor. His argument for divestment is primarily a moral one—as his platform puts it, “Climate change is the greatest threat to humanity”—but he also makes a financial case: that “investing in fossil fuels is a risky financial decision” because of the likelihood that, faced with the climate emergency, governments will eventually impose severe and costly regulations on oil companies, eroding their profits and the value of their stock.

As of March 31, 2018

| Company | Value |

| APPLE INC | $2,366,665,587 |

| MICROSOFT CORP | $2,095,285,846 |

| AMAZON.COM INC | $1,649,581,160 |

| JPMORGAN CHASE & COMPANY | $1,122,672,073 |

| BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC – CLASS B | $1,111,488,796 |

| FACEBOOK INC | $1,082,399,563 |

| JOHNSON & JOHNSON | $993,270,659 |

| ALPHABET INC (CLASS C) | $987,813,047 |

| ALPHABET INC (CLASS A) | $938,166,767 |

| EXXON MOBIL CORP | $857,464,527 |

Given the approach the Trump administration is taking to climate change, it might be optimistic to think that a government crackdown on carbon is inevitable. But Dunlea’s financial argument for divestment tracks with the established language of “socially responsible investing,” which major public pensions funds and private investment funds have engaged in for decades.

A key notion in socially responsible investing is “materiality,” or the idea that social concerns matter in the investment world when they reflect a potential financial risk—something “material” to the business. Take tobacco stocks. You can think owning those stocks is morally wrong because cigarettes are addictive products with deadly health effects. But you can also or instead think owning those stocks is financially unwise because, given the problems with cigarettes, intrusive and costly government regulation seems inevitable.

It’s the latter consideration that is supposed to matter to public pension funds and the people (like the comptroller) who oversee them. Their chief duty is to manage the fund’s investments to limit risk and improve rate of return so that retirees get the benefits they’re owed and taxpayers don’t have to foot the bill if there’s a shortfall. A risky investment is something they are supposed to be careful about.

Once a risk has been identified, however, the question is what to do about it. Divestment or divestiture—selling the stocks you have and foreswearing new ones—is one approach. Around the world, some 900 institutions have committed to divesting from fossil-fuel stocks, according to Fossil Free, an organization promoting divestment. The list includes the U.S. cities of Minneapolis, Oakland, Portland and San Francisco, as well as the state of Berlin, the cities of Sydney, Paris and Copenhagen and the country of Ireland.

To divest, or demur?

Divestment is not new. In the 1980s, it was a critical part of the boycott of apartheid South Africa. But interest in the approach is growing. According to a report issued this week by the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, the amount of money in funds that have in some way divested from fossil-fuel companies soared from $14 billion in 2014 to $680 billion this year. Fossil fuels aren’t the only target of divestment pressure: firearms, military materiel, tobacco and pornography are other products that some investors have foresworn, and companies that do business in Iran and Sudan often get the cold shoulder because those countries are identified as state sponsors of terrorism.

Friends of Mark Dunlea

Mark Dunlea, Green Party nominee for Comptroller

Since at least 2004, when the state retirement funds signed on to the Carbon Disclosure Project pushing major companies to make public their climate change impact, the New York pension funds have taken action related to carbon pollution. The pension fund was a founding signatory of the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investment in 2006, and in 2008 implemented a Green Strategic Investment Program that “committed $500 million over three years to environmentally focused investment strategies,” according to the comptroller’s office.

But the comptroller has resisted calls to divest from fossil-fuel stocks. In a 24-page report released last year that laid out the fund’s approach to environmentally responsible investing, the word “divestment” was not even mentioned. Throughout that report, DiNapoli makes clear that the environmental assessment of investments was only part of the picture. “As with any other factor, the results of the Environmental, Social and Governance Risk Assessment will be considered in the investment process alongside other factors material to financial performance, consistent with our fiduciary duty,” reads the report.

DiNapoli’s position has earned him the ire of some climate change activists. When WNYC reported this summer that Vicki Fuller, the comptroller’s chief investment officer, who had overseen the fund’s purchase of stakes in the Williams Companies—a natural gas supplier—became a member of Williams’ board of directors the same week she left her state job, calls for divestment grew. Lindsay Meiman, the communications director at 350.org, said the Fuller episode was further proof that, “We need to get dirty oil and gas money out of our politics, out of New York’s energy mix, and out of our pension funds.”

Getting out is hard to do

Within the New York pension funds’ large and shifting mix of stocks, there are signs the comptroller has moved away from at least some of the firms targeted by public scorn.

In 2010, the fund owned $14 million of British American Tobacco stock; now it holds $12 million. From 2017 to 2018, the fund’s holdings in Vista Outdoor—a firm that encompasses several brands of firearms—shrunk from $7.5 million to $999,000. In 2013, the pension fund had 45,000 shares in the gun giant Sturm, Ruger. Last year, it had none.

But there’s no explicit divestment policy guiding these moves. According to the comptroller’s office, the only industry from which the funds are officially divesting is private prisons: in July, DiNapoli announced that the pension funds had pulled out of private prison stocks.

CalPERS, the massive California public pension fund to which New York’s pension system is often compared, has a larger list of no-go areas for its investments. According to a spokesman for CalPERS, that fund has divested from “primary tobacco companies” and “companies that manufacture and make available to private persons assault-style weapons illegal for sale in California” and is subject to state laws that it aim to divest from thermal coal mining companies and firms with a significant presence in Iran or Sudan. But CalPERS hasn’t embraced full-fledged fossil-fuel divestment.

New York City’s five pension funds have. Earlier this year, Mayor Bill de Blasio and Comptroller Scott Stringer—whose office handles day-to-day management of the five separate city pension funds, each of which is overseen by an independent board of directors—committed to “a goal to divest City funds from fossil fuel reserve owners within five years, which would make New York City the first major U.S. pension plan to do so.”

Right now, the city’s pensions funds are still investors in “fossil-fuel reserve owners”—that’s the specific language of de Blasio and Stringer’s commitment—and they might be for many years, because divesting from fossil-fuel firms is not simple.

Some of the five city funds have divested from gun manufacturers and retailers and from thermal coal companies. All five have gotten out of stocks associated with the private-prison industry. But the holdings in those industries are peanuts compared with the bets the pensions have placed on oil and gas companies.

It takes time just to identify which firms are in the targeted “fossil-fuel reserve owners” class, and that’s a potentially fluid picture if oil and gas companies begin to shift significantly toward producing other forms of energy. Then the fund must figure out if it can shed those holdings without changing the mix of earnings and risks that keep the pension system stable, keeping in mind that selling or buying stocks is not free; there are transaction costs that have to be figured in.

To manage this effort, the city in April issued a request for information “to gather input and recommendations from a wide range of experts to determine a prudent strategy to divest from fossil fuel owners within five years.” The results from that inquiry will, in turn, shape a request for proposals to find someone to actually craft the process for divesting. It won’t be quick.

Engagement and alternatives

Adi Talwar

Jonathan Trichter, the Republican nominee for comptroller, has criticized DiNapoli approach to climate-related investing, and claims he'd run a 'politically neutral' pension fund.

Some argue against divestment on strategic grounds: Sell a stake in a company, they say, and you give up your chance to influence corporate behavior as a shareholder. In 2017, New York’s pension funds filed 52 shareholder proposals. Three of the proposals gained majority votes among stockholders, and 22 firms agreed to meet New York’s demands.

On environment issues, Under Armor and PayPal agreed at New York’s behest to improve their sustainability reporting, while Duke Energy, PPL Corporation and Pioneer Natural Resources promised to evaluate their ability to take steps consistent with the 2-degree temperature-rise scenario envisioned by the Paris climate agreement. Other New York shareholder proposals dealt with board diversity, executive compensation, political spending, labor standards and the use of pharmaceutical company products in lethal-injection executions.

Only seven of those proposals garnered more than 40 percent of the vote, and in a few cases, the targeted company got a green light from the Securities and Exchange Commission to dismiss the proposal for interfering with its “ordinary business operations.”

Defenders of shareholder activism say it’s a long-term effort, requiring several years of attempts before companies agree to change. But advocates have lost patience with the tactic. “DiNapoli’s repeated attempts to engage with the likes of Exxon is a failure of his fiduciary duty to New Yorkers,” says 350.org’s Meiman.

DiNapoli has taken an additional step: He had Goldman Sachs create a custom stock index—a mix of stocks meant to track the broader market—that excluded or reduced the presence of fossil-fuel companies in the mix.

“We’ve successfully shifted significant holdings to lower carbon companies without losing value,” DiNapoli said in January when announcing that he was doubling the investment in that fund to $4 billion. “Our state pension fund is at the forefront of the worldwide effort to build a lower carbon economy. Our investment decisions and our shareholder engagements are a caution to corporations: if they’re not helping build a decarbonized future, they may get left behind. Our strategy for sustainable, lower carbon investing is working and will continue to expand.”

But DiNapoli’s Republican challenger, Jonathan Trichter, says the low-carbon fund, which Goldman was paid at least $600,000 to create, is nothing but a fig leaf. “The hypocrisy is he’s paying Goldman with tax money for the privilege of having this public relations veneer to be some kind of environmental steward and to hoodwink environmental activists who believe in him and believe he’s doing something positive while continuing to invest in oil and gas companies and carbon emitters up the wazoo,” Trichter told the WBAI Max & Murphy Show on Oct. 3.

“That’s one of the problems that occurs when you try to play politics with the investment approach of the fund,” Trichter continued. “I would as sole trustee of the fund invest the money to maximize returns for individual retirees and if they want to then donate their annuities to Sierra Club then I’d like to give them the financial freedom to do that. But I’d run a politically neutral investment fund and I would invest the equity portion of the fund in passive indices that mirror the [broader markets] but I would not pick winners and losers; nor would I pick winning and losing industries.”

The fourth candidate for comptroller, Libertarian Cruger Gallaudet, told this week’s Max & Murphy show that, “I think in general the pension should be invested to get the best returns.”

Getting pressure, and applying it

What constitutes “politically neutral” is, of course, in the eye of the beholder. To some, investing in a passive stock index that you know is putting money into deeply problematic companies would seem a form of arm’s length complicity, not neutrality. The decision to focus solely on investment returns might be politically neutral in intent, but not in impact.

Trichter’s complaints about DiNapoli’s environmental record echo his larger critique of the incumbent: Trichter believes the pension fund should spend less money managing individual investments by putting money into “low-cost” index funds run by outside firms.

DiNapoli is likely to survive that critique. He leads the Republican in the polls and in fundraising. But if reelected, the comptroller will feel more pressure to take stronger action on carbon-producing companies. Last December, Gov. Andrew Cuomo urged the state pension funds to divest from fossil-fuel companies. State Sen. Liz Krueger and Assemblyman Felix Ortiz introduced in 2015 a bill to force the comptroller to, within five years, divest the pension funds from the “two hundred largest publicly traded fossil fuel companies, as established by carbon content in the companies’ proven oil, gas and coal reserves.” In the most recent session, the Senate bill had 19 co-sponsors and the Assembly version 27. It didn’t get a hearing in either house. But a shift in Senate control from Republican to Democrat could change its prospects.

As for Exxon, it has denied the claims made by the attorney general, with a spokesman telling Bloomberg News, “These baseless allegations are a product of closed-door lobbying by special interests, political opportunism and the attorney general’s inability to admit that a three-year investigation has uncovered no wrongdoing.” DiNapoli has praised the AG’s lawsuit.

Then there’s that report on climate risks that DiNapoli and the Church of England managed to get Exxon to promise. It was issued earlier this year. A state pension official welcomed the gesture, but said the company “offers too many generalizations and too few specifics on how it plans to participate in a low carbon economy” and relies on “optimistic assumptions of undiminished growth in demand for fossil fuels in certain economic sectors.” New York pension officials sent follow-up questions to Exxon. The company responded. As Exxon shareholders prepared to gather again this May, DiNapoli issued a statement saying, “the company’s response has been underwhelming.”

“Next steps are in planning,” a spokesman for the comptroller tells City Limits.

Editor’s Note: The pension fund’s embrace of restrictions is more extensive than was reported. DiNapoli divested in 2009 from companies doing business in Iran and Sudan. Then-Comptroller Carl McCall froze (meaning barred the purchase of new shares of) tobacco stocks in 1996 and DiNapoli froze holdings of firearms companies in 2013; a spokesman for the comptroller notes it “currently [has] no holdings in any company that gets significant portion of its revenue from commercial sale of firearms.”

City Limits is a nonprofit.

Support from readers like you allows us to report more.

One thought on “To Divest or Dig In: Candidates Spar Over Where to Park Pension Billions Amid Climate Threats”

Here are some important recent analyses of divestment’s financial implications, which ought to he mentioned in any discussion of the subject:

http://ieefa.org/ieefa-update-divestment-101/

http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/news/the-mythical-peril-of-divesting-from-fossil-fuels/