Data from CSS/Chart by City Limits

A new set of threats to affordable housing is looming in New York City, thanks to the Trump administration, the real-estate market and time itself, according to a report released Thursday by the Community Service Society.

The administration’s proposed cuts to the Section 8 program could cost the city tens of thousands of the federal vouchers that make the math of affordable housing work for many low-income families. And the expiration of affordability agreements tied to Low-Income Housing Tax Credits could mean thousands of other units end up on the open market, with the Trump tax cuts making it harder to issue new credits that close the gap.

Those worries add to existing concerns about Mitchell-Lama developments and project-based Section 8 buildings going market rate. Nearly a third of the 119,000 units in those programs shed their affordability restrictions between 1990 and 2008.

The existing problem and the new risk all stem from the way affordable housing programs were structured in the 1970s and 1980s. “Subsidized housing as a concept exists because the government at a certain point decided that it wanted to really subsidize private development of affordable housing as opposed to building housing directly,” says Oksana Mironova, a housing analyst at CSS (City Limits’ former parent organization and a current funder) and an author of the report, Closing the Gap: Subsidized Housing at a Time of Federal Instability. “And to do that most subsidy programs that exist were built kind of with an escape valve, which is that as long as the subsidy is active within a building, it’s affordable, but when the subsidy ends the owner has the option to leave the program. So that means that there’s usually like a 20- or 40- or … with some programs a 60-year period when it’s affordable.”

The timeline gives building owners options but, says Mironova, “We know that sometimes this is really, really bad for tenants.” Losing subsidized units is more than just a financial hit, she notes: Not only are rents more reasonable in such apartments, but “the rights of the tenants are really well-defined.”

The pace of the losses of subsidized housing has slowed since the recession. “What we’re seeing is not as bad by any means as it was in 2005, 2006,” Mironova says. “This administration has been focusing on preservation much more directly than the previous one so we’re not losing as many units—but there are still a couple of buildings that leave every year.”

Some Mitchell-Lama developments whose affordability agreements have recently expired ended up signing new regulatory agreements — preserving the units, though sometimes at a significant cost to the city. That’s prompted questions about whether those deals offer the best bang for the city’s housing-affordability buck, in part because some residents of the city’s 180,000 units of subsidized housing—especially some who live in Mitchell-Lama buildings–would not be considered low-income.

“You end up with different income levels,” in many buildings, Mironova says, because of the mix of subsidy and voucher programs involved. “It gets very messy when you look at individual buildings about whether you are supporting low-income or moderate-income people by preserving the building. But certainly, we need to do both.”

But if the wave of affordability exits that crested before the 2007-2009 recession has ebbed, a new one appears to be building, driven by the expiration of contracts under the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program.

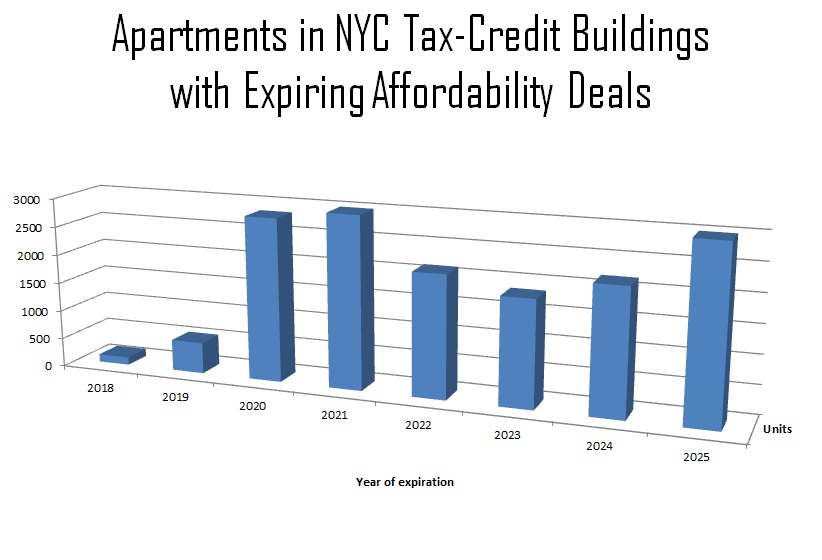

LIHTC allows affordable housing developers to sell tax credits that corporations use to reduce their federal tax bill. The developers use the proceeds from those sales to create housing, and must promise to keep that housing affordable for a set number of years, usually 15 or 30 years depending on when the credits were sold. It’s become the dominant form of affordable-housing construction finance in the city since New York’s first tax-credit building was financed in 1988. The first major waves of expirations will begin in 2020.

“We don’t exactly know what it’s going to look like,” Mironova says. But those time limits will toll at 300 developments encompassing more than 15,000 units in the city over the next seven years, according to CSS.

Recent tax-law changes could make it costly to renew those LIHTC deals. Since the Trump tax cuts reduce corporate taxes, the value of low-income tax credits will likely also be reduced. Cheaper tax credits means less money to spend on housing, whether building it new or renewing expiring affordability deals.

“A response will require unprecedented coordination,” CSS’s report concludes. “Unlike older types of subsidized housing, LIHTC regulation and oversight is dispersed among multiple parties, including syndicators like Enterprise Community Partners and the National Equity Fund, housing finance agencies like [the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development] and [the state Department of Homes and Community Renewal], and the IRS.”

Another complication: Many affordable housing developments combine multiple subsidy programs to build and then operate the housing. LIHTCs on their own cannot create rents affordable to many low-income people—they’re used to build rather than operate the housing, Mironova says—and so must be used in tandem with Section 8 vouchers.

To address the looming threat, CSS recommends bold action by New York State—creating an operating subsidy for affordable housing, establishing a state rental voucher program, strengthening rent regulations and establishing a task force to map out a response to the LIHTC problem. It’s an ambitious ask for a governor and state legislature who, in spite of a profound affordability crisis, have managed only modest improvements to rent regulations.

“There needs to be the political will to make this extensive wish list to happen,” Mironova says. Some sort of new state support for affordable housing, whether a new subsidy to building owners or a new voucher for renters, is a baseline necessity, she says. As for the threats to LIHTC housing, there is little choice but to respond. “Somethings going to happen no matter what, just because we’ve seen how this has played out before with the project-based Section 8 buildings,” she says. “It is something that the agencies that have oversight responsibility need to be thinking about as a whole, and as a problem that will occur very soon.”