Abigail Savitch-Lew

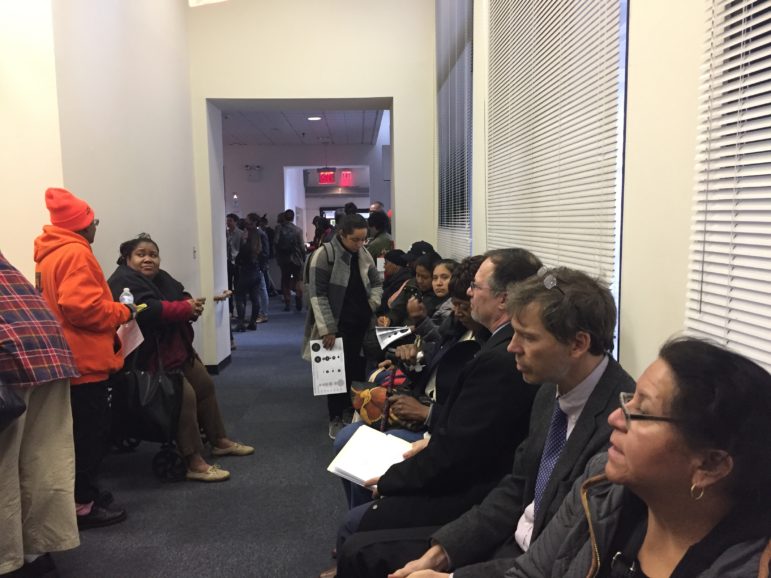

The hallway outside Spector Hall, where the City Planning Commission held its hearing on the Jerome Avenue rezoning on Wednesday. With the hearing room filled to capacity, there was at one point about 40 people standing or sitting in the hallway, many waiting to testify.

On Wednesday morning, the City Planning Commission heard five hours of testimony from the public on the Department of City Planning’s proposed Jerome Avenue rezoning. It’s the latest step in the seven-month process through which the rezoning—the fourth of de Blasio’s neighborhood rezonings to promote housing development, and the first for the Bronx—will be approved or disapproved.

Among those who signed up to speak in favor of the rezoning were city representatives who detailed their agencies’ investments and initiatives in the area and a couple for-profit affordable housing developers. Multiple members of Community Boards 4 and 5, a representative from the Bronx Borough President’s office, a few non-profit affordable housing developers and others expressed support conditioned on a variety of additional initiatives and investments.

But more than half of those who spoke—and others who had to leave for work before their name was called—opposed the plan and expressed deep concerns, mostly about the impact of the rezoning on residential and business displacement and the rent levels of the potential new housing.

Local councilmembers Vanessa Gibson and Fernando Cabrera, who will have the ultimate say on the proposal, expressed optimism about the rezoning while saying there was more to be done. “This plan cannot and must not move forward without community support,” Gibson said, emphasizing that the plan had to benefit existing residents. Yet she also said she was unwilling to give up an opportunity for neighborhood investment and growth: “If we do nothing and sit back, we are not going to get the neighborhood that we rightfully deserve.”

The CPC asked many questions, contributing to a vibrant discussion. Here are a few key takeaways.

•The Poorest New Yorkers…and Poorest Americans— Of the neighborhood rezonings initiated under de Blasio, Jerome Avenue has the greatest share of extremely low-income residents. According to census data pulled by the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development last year, 45 percent of households make less than $20,000 (or roughly below 30 percent Area Median Income). In 2010, this part of the Bronx was also the poorest of all congressional districts in the country. Advocates and residents point out that even the least expensive housing created through the city’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy would not yield units affordable to these residents.

There’s evidence that the market is weak enough that developers in the near-term would need the support of city subsidy, and thus be required to abide by affordability termsheets that require at least 10 percent of apartments to be affordable to such families (and another 10 percent for formerly homeless families in most termsheets). At least that’s what a couple for-profit developers said at the hearing. But some advocates are concerned that there’s no telling how long developers will continue to rely on termsheets. Land prices are already rising, as William Bollinger of JCAL Development Group LLC confirmed.

Several residents who said they made below $20,000 explicitly asked the commissioners to respect their dignity and local expertise. “A lot of us are struggling and a lot of us are disabled,” said Madeline Mendez, who identified herself as a disabled tenant relying on a Section 8 voucher. “You don’t think about us…because you can afford this ‘affordable housing.'”

Michelle Genross, who makes $14,000 a year, told the commission, “We’re human too…we are all doing the very best we can and we need to be recognized. We don’t need to be thrown away like trash.” Some also spoke to the problem as a matter of racial discrimination and “ethnic cleansing.”

The demand for housing for families in the lowest income bands is by far greater than the demand for moderate-income families making 80 percent Area Median Income ($68,720 for a family of three), according to Alexa Sewell of Settlement Housing Fund. Gibson and Highbridge CDC President Monsignor Donald Sakano, however, argued that having a mix of affordability levels was also important; Gibson mentioned the need for housing for those making between 40 percent and 60 percent AMI ($34,360 to $51,540 for a family of three).

•Predatory Equity At Large – There’s already a major problem of landlords, including predatory equity companies, buying rent-stabilized buildings and trying to displace residents through harassment or through Major Capital Improvements (renovations for which landlords can apply for an increase in stabilized rents). Many residents are concerned a rezoning will only exacerbate this trend.

While advocates lauded the soon-to-be-approved certificate of no harassment pilot program (which will require landlords to prove they have not harassed tenants before renovating or demolishing a building), they say further steps are needed to protect tenants. Sheila Garcia, director of the tenant organizing group CASA, called on the city to implement a “no net loss” policy that would involve tracking the number of affordable units that are “lost,” and commit to replacing each such unit at the same rent levels. Others said the new Neighborhood Pillars program, which will invest in nonprofits to buy rent-stabilized buildings, is the right direction for city policy. The need for better enforcement of the state’s rent-regulation laws came up repeatedly.

Some commissioners shared advocates concerns that the city’s environmental review methods don’t take into account the displacement risk faced by tenants in rent-stabilized housing, and both agreed on the need for more analysis of the risk faced by such buildings.

•School seat deficit – Councilmember Gibson, and both proponents and critics of the rezoning said the deficit of school seats was egregious. The rezoning covers two school districts, including many already over-crowded schools, with a predicted deficit of 4,653 seats by 2026 without a rezoning. Development ensuing from the rezoning is predicted to bring another 2,388 students by that year. Community Board District Manager Paul Philipps said that there are some large city-owned sites in the area on which schools could be built but that those sites are “tied up.” He said that without those properties available, it will be necessary to work with private developers; a couple have already offered or are exploring the possibility of siting a school. Community Board 5 District Manager Ken Brown said their board is researching the possibility of expanding existing schools.

Of course, school seats were not the only kind of infrastructure in demand: stakeholders made a call for health services, community centers, increased transit and more.

•Fate of Auto Sector Many advocates voiced concerns about the threats faced by the auto-industry along the Jerome Avenue corridor, which are a source of well-paying blue-collar jobs for many workers. Gibson called for the city to make investments in workers, in technology upgrades, and in incentives to landlords to engage in long-term leases. Others, including the Borough President’s office, the Municipal Art Society, and the Pratt Center for Community Development, spoke about the need to expand the “retention zones” where auto-industry zoning will remain in place. There were many calls for a more substantially developed and funded relocation plan for any displaced auto-workers.

It’s also true that some residents would like to see more diversified retail along the corridor. But Conte said that, given the high wages of the auto-sector relative to the retail sector, it was necessary for the city to think more thoroughly about “what’s the balance we want and how we’re going to strike it—not just say, ‘oh we want a mix.'”

•Development and Jobs – 32BJ signed up to speak in support of the rezoning and asked for guarantees that developers pay prevailing wages and hire locally. In contrast, a few construction workers and labor advocates signed up to speak against the rezoning and hammered home their concern that building contractors were relying on untrained workers, and that the city’s affordable housing projects too often relied on exploitative contractors. “Lives are made dispensable by the fact that you need to build these buildings as cheaply as possible,” said an advocate with the NYC Community Alliance for Workers Justice.

A representative from JobsFirstNYC spoke about the ongoing efforts in the area to start a workforce referral network that will connect local residents to jobs. With her questions, Commissioner Michelle de La Uz suggested the importance of not only building a job referral network, but also providing more seats for workforce training and literacy.

•Conditional support from nonprofit developers – The nonprofit developers Services for the Undeserved, Settlement Housing Fund and Highbridge CDC each testified in support of the rezoning, but also expressed their understanding of the displacement risks involved. Services for the Undeserved described in detail two affordable housing projects they would like to embark on, one located in the expanded version of the rezoning.

Settlement Housing Fund’s Sewall emphasized the importance of investing in preservation and improved state enforcement of rent regulations, among other recommendations. “Markets rise and it’s inevitable with the rezoning or not that these units will come out of regulation,” she argued. She also called for outreach to current property owners—as well as brokers—to help them understand the city affordable housing programs available and prevent them from engaging in speculation, which could take land prices beyond the reach of nonprofit affordable housing developers.

HIghbridge CDC’s Sakano also called for nonprofit ownership, enforcement of existing regulations, a more efficient approval process for housing development, and other measures. He also said he supported many of the Borough President’s recommendations.

Later, commissioners asked a representative from the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development to discuss the proportion of non-profit to for-profit ownership in the area. The HPD representative said the agency had not yet determined the percentage of for-profit and non-profit ownership, but agree it was a “critical piece” in formulating an anti-displacement strategy.