Department of City Planning, Brownsfield Opportunity Area Nomination Report

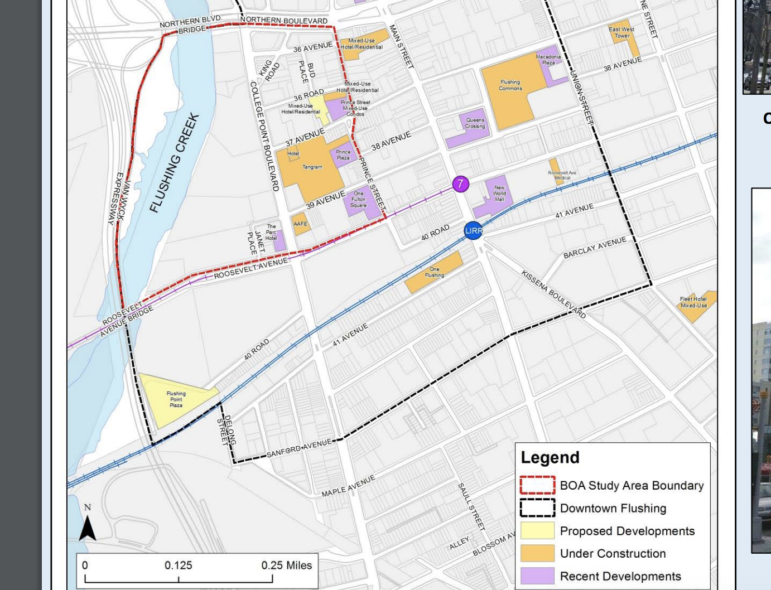

A map of development occurring in the Flushing West area as of March 2017.

Many New Yorkers are already debating the impact of de Blasio’s first neighborhood rezoning in East New York, where income-targeted housing construction is on the rise, but speculation, especially in the market for single-family homes, is a looming cause for concerns. Less attention has been given to the rezoning that was not—or at least not yet: Flushing West.

The Flushing rezoning plan, which was shelved in June of 2016, would have applied to an 11-block area east of Flushing Creek and west of Flushing’s Prince Street. The area includes a mix of vacant, underused and industrial sites, especially close to the waterfront, as well as new high-end commercial and condominium buildings on the eastern side. The rezoning would have increased allowable density while requiring a percentage of income-targeted housing under the city’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy. While it was expected that the area would continue to grow without a rezoning—with another 2,400 market-rate residential units by 2025, by the city’s estimate—with a rezoning, the Department of City Planning (DCP) estimated there would be an additional 267 market-rate units and between 464 and 557 income-targeted units. (The city also predicted that, if the developers applied for waivers from La Guardia airport height limitations, there might be as many as 423 new market-rate apartments and between 515 and 619 income-targeted apartments.)

Local Councilmember Peter Koo, however, requested that the rezoning be withdrawn due to a myriad of concerns, many related to the area’s already overtaxed infrastructure. In turn, DCP had its own concerns about the feasibility of an upzoning as the result of the area’s high water table and height regulations due to the proximity to LaGuardia airport.

The Flushing Rezoning Community Alliance, a coalition of residents, faith leaders and others who were organizing around the plan, had mixed feelings about the rezoning’s withdrawal: While they’d had concerns about the rezoning, and put forth demands for deep affordability and anti-displacement protections, they now feared that they’d lose the benefits of proposed city investments and income-targeted housing altogether. And the alliance still feels this way, as they explained in an e-mail to City Limits this week: “More than a year after the Flushing rezoning has been stopped, there are both good and bad consequences from that decision.”

In the year and a half since the rezoning was dropped, development has continued in Flushing West without a requirement for income-targeted housing, especially on the eastern side. The planning, however, isn’t over: the city has published a report of recommendations to improve the quality of the waterfront area and is encouraging private developers to undertake changes voluntarily, which means substantial changes could still be in the neighborhood’s future, though with less density and with fewer income-targeted units.

As for the community, Flushing has received some, but not all, of the extra investments and initiatives received by other rezoning neighborhoods.

A hot market, without affordability requirements

Flushing as a whole has continued to be one of the city’s hottest neighborhoods. In the third quarter of 2017, three new Flushing apartment buildings were among the top ten best-selling condos in the five boroughs. One was Flushing Commons, where the median sales price for a condo was over $1 million. Asking rents in the area increased from $1,850 in 2015 to $1,950 in 2016—meaning Flushing families are increasingly crunched.

Development is also occurring on some sites of Flushing West under as-of-right zoning without the income-targeted housing requirements. In its 2015 draft scope of work for the rezoning study, DCP identified about 26 sites in the area that were ripe for, or already beginning development. According to an overview conducted by DCP in March, four of those 26 sites were now under construction or had developments proposed on them, all on the east side closer to Prince Street. One of those developments will be the mammoth Tangram project by developer F&T, including a 4D multiplex movie theater, condos and office space. The waterfront area remained a bit quieter, but there’s been some significant sales: one large site, purchased in 2015 for $78 million, was resold last week for $115 million to real estate investor Yuk Ming Yip, The Real Deal reports.

Further study would be necessary to evaluate how the rezoning’s cancellation affected development trends in the area. The answer might depend on which parcel, specifically: a block that the city proposed changing the zoning from a manufacturing designation to a mixed-use designation would have been more affected by the rezoning’s cancellation than a block where the rezoning would have increased density marginally without changing a parcel’s use.

For instance, Joyce Cheng of Prince Property Development, the owner of 134-20 36 Road, is moving ahead with plans to build a hotel and some residential units (none income-targeted). Her site was already zoned for commercial and residential uses, and she told City Limits that the rezoning’s cancellation had not mattered to her and that she might be better off without it.

On the others hand, the nonprofit development organization Asian Americans for Equality owns a site in the area (already zoned for a commercial and residential mix) and had planned, when the rezoning was pending, to build a seven-story building including community-space and below-market office space. Architect Peter Bachmann expressed concerns that because the rezoning, which would have lessened the parking requirements for the site, had not passed, the feasibility of the project was now in question. (In either case, AAFE hadn’t intended to build housing.)

It’s often argued that rezonings add fire to a market by enabling increased building density and also drawing attention to an area—and this certainly was expected to be the case in Flushing. Yet it also may be that for some parcels, developers preferred the cancellation of the rezoning. Koo, in his 2016 letter against the rezoning, said developers had told him that because of the high water table and La Guardia airport flight limitations, the rezoning, by requiring mandatory inclusionary housing, could actually deter development.

“They couldn’t go lower and they couldn’t go higher,” explains Alexandra Rosa of the Flushing Willets Point Corona Local Development Corporation, which has been spearheading revitalization in the area. “They were sandwiched and that sandwich was what created the financial difficulties here.”

While income-targeted housing isn’t required in the Flushing West area, another site a few blocks away recently received approval for an upzoning, which means it will be required to provide a portion of below-market units under the mandatory inclusionary housing policy. 27 of the 93 units in the nine-story building at 135-01 35th Avenue will target households making up to $68,720 for a family of three.

Planning efforts not over

The Department of City Planning did not simply jump ship after the rezoning was shelved. The rezoning proposal had actually emerged out of a study on waterfront revitalization that DCP was under contract to complete on behalf of the Flushing Willets Point Corona Local Development Corporation, which had received a state Brownfield Opportunity Grant to explore how to revitalize the area next to Flushing Creek. The LDC, it’s been noted, has several Flushing property owners among its members.

Because DCP is no longer undertaking a rezoning itself, the city’s report, completed in September, basically functions to provide a voluntary roadmap for private property owners, showing them how they could improve waterfront access and the neighborhood’s desirability in the event they chose to redevelop.

A presentation on the report released in May indicates that in some ways the report echoes the original rezoning plan but is narrower, focusing on the properties closest to the waterfront where there are more challenges to develop. It recommends the creation of a special district with zoning mechanisms that would require additional spaces for public waterfront access, a new, privately maintained street grid, flexibilities in building design regulations to address the obstacles to development like the high water table and height limitations, and a rezoning limited to a small portion of the area that is currently zoned for manufacturing. The city predicts that its recommendations, if undertaken by private property owners, could lead to an additional 222 apartments more than what is expected without a rezoning, which would include between 56 and 67 income-targeted units.

The LDC is using DCP’s report to advocate to the Department of State that the area be officially designated a Brownsfield Opportunity Area, which would allow property owners to get tax breaks for remediating and redeveloping properties according to the city’s plan. And it’s now up to the private property owners to move on those suggestions.

“The property owners have been meeting among themselves and with DCP to advance the development proposal included in the [Brownsfield Opportunity Area] nomination study,” says the LDC’s Rosa. Referring to the real estate investor Yip, she said, “We have to give him time to acquaint himself with the nuances and details of the nomination study and the linkages with the other owners. So our hope is that the owners will continue to meet and to develop the properties in accordance with the nomination study that would open the Flushing waterfront to the community and create planned cohesive development.”

Last December, the Flushing Rezoning Community Alliance expressed concerns to City Limits about a plan that adds value to the waterfront without providing any income-targeted housing (the city says the recommendations in its report would lead to the creation of only about 60 income-targeted units). Still, Koo’s office supports the city’s recommendations: “It is on everybody’s radar and there’s an agreement that that would be a benefit to the neighborhood,” says Sieber, referring to an activated waterfront.

Half of the special treatment

The De Blasio administration has argued that its rezonings are shaped by comprehensive neighborhood planning processes and come with a suite of investments ranging from streetscaping to the creation of new job centers. But many targeted neighborhoods are asking: Do you have to agree to the rezoning to get the investments?

Flushing provides a complicated answer. On the one hand, like other rezoning neighborhoods Flushing has a Tenant Support Unit (which helps connect tenants to legal services), according to the website of the Human Resources Administration. Like other rezoning neighborhoods, it received resources from the Department of Small Business Services to complete a Commercial District Needs Assessment of its commercial corridors, as well as a few million in funding to undertake some of the assessment’s recommendations. And the city has also moved forward with other projects originally promised during the Flushing West rezoning discussions, like sidewalk widening and other improvements to Main Street and the release of a Long-Term Control Plan to mitigate sewage overflows into Flushing Bay (though some have questioned the sufficiency of those plans).

On the other hand, there are also resources that Flushing has not received that at least some other rezoning neighborhoods have. For instance, in May the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) said it was making a special effort to ramp up code enforcement in East Harlem, Jerome Avenue, and Inwood. The new Landlord Ambassador program, which focuses on helping owners apply for HPD financing, is currently being piloted in three areas of the city where rezonings are concentrated: Northern Manhattan, East and Central Brooklyn, and South and Central Bronx. Flushing was not listed, at least initially, in either effort, though both code enforcement and landlord outreach were identified as key needs during the Flushing planning process.

“When Flushing West stopped, a lot of those discussions possibly slowed down a bit, but they’re still happening on a more specific basis…it’s incremental improvement,” explains Scott Sieber, a spokesperson for Koo, speaking about investments in infrastructure and other community needs.

However, bigger problems that Koo felt made a rezoning unwise, like overcrowding on the 7 train, still need to be addressed.

“There are still huge needs around infrastructure and transportation, better parks and open spaces, additional senior centers and senior services, and so much more. At the same time, having less market-rate housing than what was anticipated in the rezoning may have helped to assure that these concerns were not made worse in the short term,” wrote the Flushing Rezoning Community Alliance in their e-mail to City Limits. “However, what is very clear is that the dire need of income-targeted housing for low-income tenants in Flushing has not been met. As development surges forward in Downtown Flushing, there is little to no income-targeted housing being constructed that meets the needs of the largely immigrant families in Flushing that are desperate for truly income-targeted housing.”

The coalition’s Pedro Rodriguez, manager of the pantry at St. George’s Church, says there’s several concrete steps that could be taken to address both the infrastructure and housing problems. He wants to see Municipal Lot 2, a parking lot, redeveloped with income-targeted housing. Koo has said in the past that the lot provides badly needed parking in the neighborhood, but Rodriguez says it would be better to encourage people to park their cars in the large parking lots of Flushing Meadows Park. He’d also like to see a bus depot in Flushing Meadows Park to ease traffic downtown.

Koo is also interested in other planning efforts. He says the Council is funding a Flushing study by the Regional Plan Association that will look more closely at the long-term infrastructure and planning needs of the district, and that he’s also interested in exploring whether the industrial areas north of Flushing West might be appropriate for a rezoning.

Meanwhile, the Flushing Rezoning Community Alliance has turned some of their energy to citywide policy battles. Faith in New York and other members of the alliance held a candidate forum and produced a City Council candidate survey that asked Koo and his challenger in the Democratic primary Alison Tan to articulate their positions on things like the creation of a citywide certificate of no harassment, the creation of a termsheet with deeper affordability requirements, and the passage of the Housing Not Warehousing Act. Koo, who beat Tan and ran unopposed in the general election, said he supported all three.

2 thoughts on “Flushing: the Case of a Rezoning Postponed”

Pingback: Coeur Mining (NYSE:CDE) Given Coverage Optimism Score of 0.07 - StockNewsTimes

Pingback: Coeur Mining (CDE) Getting Somewhat Critical Press Coverage, Analysis Finds - StockNewsTimes