Michael Appleton/ Mayoral Photography Office

The mayor has consistently highlighted the crime statistics, as did predecessors Giuliani and Bloomberg.

Assemblywoman and Republican mayoral nominee Nicole Malliotakis came out on Friday with another television ad—a skillfully crafted piece of propaganda that revolves around a dark fantasy of what life in the city is like under Mayor de Blasio. There is no doubt the ad’s loose logic and broad-brush imagery will be effective among some New Yorkers. The only question is whether those who take it to heart will line up to vote for Malliotakis on Tuesday, or pack up the family and pets tonight and get out of town before the rats and the homeless people join forces to kill us all.

In the ad and throughout her campaign, Malliotakis unfortunately bases much of her offense around the tired Republican playbook of blaming progressives for fiscal disaster and urban mayhem. Concerns about rising crime are usually part of that rhetoric. They’ve never had much logical basis but there used to at least be some statistical evidence to allow a rough correlation between Democrats in City Hall and rising violence.

Since taking office in 1994, however, de Blasio has severed that linkage: Crime is down and keeps going down despite significant decreases stops, frisks, arrests and incarcerations. Rather than acknowledging this fact or just not talking about it, Malliotakis has cherry-picked a few crime categories whose numbers have run counter to the citywide trend in a lame attempt to create a more convenient narrative.

One thing she’s honed in on is the category of “felony sex crimes,” a category that—as City Limits (and others) have pointed out—contains sexual offenses other than rape, because rape is included with the other six “major felonies.” Crimes like sexual abuse, course of sexual conduct against a child, obscenity, incest, and disseminating indecent materials to minors are in this category. They’re pretty rare: There were 1,300 such crimes reported in 2016, compared with 21,000 felony assaults.

In the past few days, an odd dispute has broken out over this small piece of territory in the city’s crime map. It began on Wednesday in the final mayoral debate when CBS2’s Maurice DuBois asked Malliotakis where she was getting all this crazy “felony sex crimes” stuff, because the NYPD says it’s not true. Malliotakis was flabbergasted, and she wasn’t alone. De Blasio piled on, indicating he had no idea where she was getting her numbers. It came up again on Friday on WNYC’s Brian Lehrer asked the mayor about Malliotakis’ contention that “sex crimes are up.” The mayor replied:

“First of all, as the moderator of the debate had trouble understanding where the assemblymember was getting her statistics from and I’ve talked to the folks who are the key statistical analysts at the NYPD—no one quite understands where she’s getting these numbers. But we do know that we’ve seen some real challenges with sexual assaults. NYPD is shifting, consistently, more resources to address the problem. Now I will say, most importantly, we have seen a decline—thank God—in rape from last year to this and we want to keep driving that decline.”

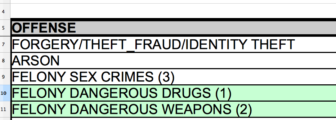

But the mystery of where Malliotakis gets the numbers is fairly easy to solve. It’s right there in the spreadsheet called “non-seven-major felonies” that launches off the NYPD’s “historical crime statistics” page. That is where, if you squint really hard, you will see this (green highlighting in the original):

At the mayor’s crime statistics press conference on Friday afternoon, the police department’s top statistical guy, Chief Dermot Shea, addressed the matter. “There’s a category, it’s not ‘felony sex crimes’, it’s ‘felony sex crimes other than index crimes.’ That’s probably where the confusion lies,” he said. Of course, that’s not actually what the category is called. But it’s what the category means. Right?

Right. So the labeling can be misleading and Malliotakis has exploited that. But there’s no mystery where her numbers or her nomenclature came from—right from the same NYPD statistics that de Blasio so often boasts about.

The problem with the term “felony sex crimes” is, as Shea indicated, that it sounds like it should include all sex felonies, when it doesn’t include rape. If we did look at all felony sex crimes—rapes and the other ones reported in the category Malliotakis has focused on—they’d be up about 13 percent from 2013 to 2016. The NYPD says rape is down so far this year, but didn’t indicate on Friday what the numbers for the other felony sex crimes look like in 2017.

| YEAR | RAPE | ‘FELONY SEX CRIMES’ | TOTAL |

| 2000 | 2,068 | 1,839 | 3,907 |

| 2001 | 1,981 | 1,831 | 3,812 |

| 2002 | 2,144 | 1,513 | 3,657 |

| 2003 | 2,070 | 1,295 | 3,365 |

| 2004 | 1,905 | 1,263 | 3,168 |

| 2005 | 1,858 | 1,162 | 3,020 |

| 2006 | 1,525 | 1,096 | 2,621 |

| 2007 | 1,351 | 1,031 | 2,382 |

| 2008 | 1,299 | 909 | 2,208 |

| 2009 | 1,205 | 914 | 2,119 |

| 2010 | 1,373 | 1,053 | 2,426 |

| 2011 | 1,420 | 1,028 | 2,448 |

| 2012 | 1,445 | 1,380 | 2,825 |

| 2013 | 1,378 | 1,073 | 2,451 |

| 2014 | 1,352 | 1,135 | 2,487 |

| 2015 | 1,438 | 1,152 | 2,590 |

| 2016 | 1,438 | 1,336 | 2,774 |

| Change 2013-2016 | 4.35% | 24.51% | 13.18% |

There is a bigger problem here than a poorly named row on an NYPD spreadsheets, or the mayor’s suggesting his opponent is making something up when she’s not, or Malliotakis deliberately missing the forest for one lonely tree.

Shea indirectly illuminated this larger problem when talking earlier during Friday’s press conference about a slight rise in reported rapes in October. Looking at all the rapes reported last month, several were incidents that allegedly took place years ago, but the victim only came forward now. Relatively few were alleged “stranger” rapes. A third of the cases involved husbands allegedly raping their wives. And 55 percent were in a category that would once have been called “date rape” — boyfriends allegedly attacking girlfriends, that sort of thing.

The point is that the rape number goes up or down based on multiple independent factors. Some of those factors are more affected by crime suppression efforts than others. But the NYPD crime statistics are treated like a monthly stat-sheet on how well the NYPD is doing at suppressing crime. When the numbers go down, the police and their political leaders are praised. When they go up, the leadership is criticized.

But that was never the intention when the NYPD moved in the early 1990s to elevate the use of data. The stats are meant to inform decisions about crime-fighting strategies—for instance, as Shea said, the spousal rape numbers make clear the importance of the city’s broader efforts to combat domestic violence. The crime numbers aren’t supposed to be a month-to-month barometer of how well the mayor and police commissioner are doing. Yet that is what they have become.

This off-label use of the crime stats as political messaging has for the most part proven convenient for mayors. It created Rudy Giuliani’s national reputation, allowed Mike Bloomberg to justify letting Ray Kelly run the PD with very little mayoral oversight and let de Blasio counter the suspicion that New York would turn into a war zone during his tenure.

But this sex-crimes episode has made clear why the prominence placed on the stats is problematic: It leads us into a discussion that really has nothing to do with the broader thrust of crime and justice in the city.

However much he or his opponent spin and counter-spin the data, the low and sinking crime numbers will likely help de Blasio get a second term. If he wins, maybe the month to month City Hall focus on crime stats is something that can end. With crime this low and the neighborhood policing model taking hold, the stats on reported crime will have less and less to do with what the NYPD does day to day or what law and order really looks like in the city.