Adi Talwar

Lincoln Medical Center at 149th Street and Morris Avenue in the Bronx, one of the H+H facilities facing a multifaceted crisis.

Call it the seven-year itch.

Upending a standing state-city agreement to support the state’s largest public hospital system, Gov. Andrew Cuomo kept a much needed $380 million in matching federal money out of reach of NYC H+H for months this summer and into the fall, while he seemed to go out of his way to dispense his largesse elsewhere –money, personnel and disaster relief to hurricane-devastated Puerto Rico; $25 million in biotech innovation for Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Center in Long Island; appearing on Staten Island to announce new measures to crack down on fentanyl abuse (part of a $200 million state investment in prevention, treatment and recovery) — all the while, loudly criticizing President Donald Trump for his efforts to undermine and dismantle the benefits of the Affordable Care Act.

Last week, the dramatics seemed to end after outgoing head of the NYC H+H Stanley Brezenoff threatened a lawsuit to force the governor to relinquish the money. Late Friday afternoon, state Medicaid Director Jason Helgerson released a letter to the press announcing that the city hospital system would receive $360 million for its annual allocation.

Never mind what happened to the millions that appeared to be deleted from the accounting, the larger question remains: what does this mean for the future?

Seven years ago, when the New York City Health and Hospital Corporation – now known as NYC H+H – was facing a projected deficit of $1.2 billion, then HHC president Alan Aviles worked out a deal: if the state and city were willing to provide matching funds to help the hospital system continue operations, HHC would hire an outside consultant to guide the hospital system through a reorganization.

Under the agreement, the state would provide $300 million in disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments – money the federal government gives the states each year to help cover the costs of serving the uninsured – if the city would provide an equal amount. The idea of the plan was to find an additional source of revenue for the hospital system and carry out an internal reorganization to move the hospital system out of the red.

Hearing the Call to Help, Closing the Gap on Health

A Bronx church is both a place of worship and a community center that draws people of different religions and cultures in by providing resources that are inaccessible to them in traditional clinical facilities.

Read more.

* * * *

Flash forward to the present and NYC H+H is in even greater financial straits than in 2010. Today, the hospital system, which serves more than one million patients a year, 400,000 of whom are uninsured, has a current deficit of $1.2 billion, projected to rise to $1.8 billion by 2020, despite the increase in the annual level of support from the city: from $1.3 billion in 2013 to $1.8 billion this year and to a planned $1.9 billion in 2020.

While H+H has cut its 43,000 workforce by 10 percent, closed clinics and shuttered Goldwater hospital (shifting patients to Harlem hospital), it struggles to attract patients with commercial insurance and to hire doctors and nurses to fill the ranks of those who have left. It also has struggled with updating an aging system whose physical infrastructure belies a level of care that matches or in some instance excels that of five of the largest private voluntary hospitals in the city, according to the Leapfrog Group, a national hospital industry quality measure organization, which rates hospitals on a set range of patient safety metrics.

In an October 2017 report funded by the New York State Nurses Association, “On Restructuring the NYC Health +Hospitals Corporation,” Barbara Caress and James Parrott argue that much of NYC H+H’s problems can be laid squarely at the feet of Albany and the private voluntary hospital system in New York City, the latter for its tendency to offload its more expensive and less remunerative patients onto the public health care system.

“The fact of the matter is that NYCH+H increasingly picks up the cost of a wide range of services and populations that private sector providers can avoid precisely because NYCH+H is there to assume this load,” the writers maintain. Six of the 11 NYC H+H hospitals have Level 1 trauma centers, reducing the pressure on private, voluntary hospitals to provide that kind of emergency care. The public hospitals treat more patients, treat more uninsured and under insured patients and treat patients with highly complicated—but not necessarily well reimbursed—care. H+H is also the largest provider of addiction and psychiatric services in the city.

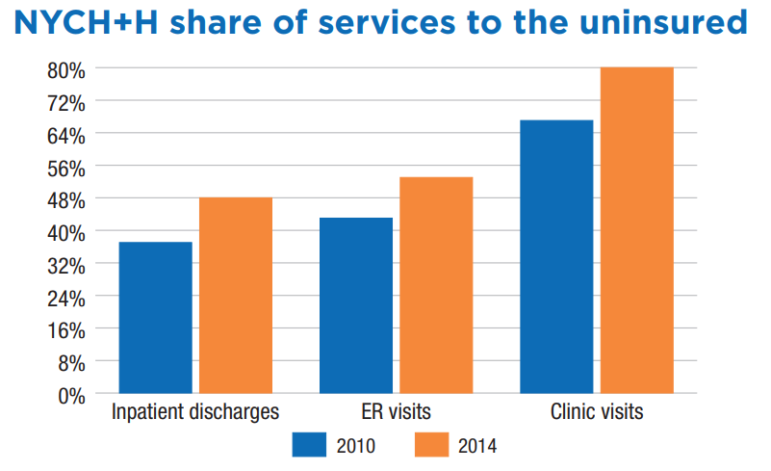

This chart, from a recent New York State Nurses Association Report, illustrates the growing role H+H is playing in the indigent care universe.

In March of this year, the eight-member Commission on Health Care For Our Neighborhoods, made up of health care representatives and community advocates from the New York Academy of Medicine, the United Hospital Fund, Community Service Society and Make the Road, which was convened at the request of Mayor Bill de Blasio, released its “Recommendations on NYC H+H’s Transformation,” an update to the mayor’s 2016 H+H rescue plan. In its report, the commission noted that the public hospital system handled nearly half of all uninsured hospital stays and emergency room visits, and 80 percent of nonemergency hospital visits. At the same time, “the system is projected to experience a decline of nearly $1.2 billion in traditional safety net funding through 2020. This is primary because of federal DSH cuts statewide,” the report writers noted.

(This year, under a timetable set by the Affordable Care Act, federal disproportionate share hospital money will decrease to states, as the ACA drafters assumed that with more people enrolling in insurance plans under the ACA, less federal DSH dollars were needed to cover the cost of uninsured care. While Congress voted to delay the institution of the reduction since 2014, this past Oct. 1, Congress allowed the timetable to go into effect.)

Meanwhile, with its accounting so deeply in the red, the public hospital system has few resources left over to compete with five of the city’s largest private hospitals — NY-Presbyterian Weill Cornell, NYU Langone, Montefiore, Mt. Sinai, Northwell — all of which have the money to make new investments in expanding their campuses, invest in new technology, and build out public affairs/development departments nimble enough to pepper the city with catchy billboards trumpeting their care all the while remembering to send out cheery “how did we do?” emails after discharges.

According to the NYSNA October report, in 2016, the five hospitals reported net operating revenues of $877 million, while the public hospital system is facing a deficit of more than one billion dollars.

So, what’s the future for NYC H+H?

While neither the public hospital system nor the mayor’s office wanted to comment on the state’s announcement last week of the belated payment of H+H’s federal hospital funding, the NYSNA report laid out some alternatives for sharing the responsibility for caring for New York city’s poor and working class families.

Among the suggestions: The state could reframe the guidelines for the state’s Indigent Care Pool to award dollars based on the percentage of charity care given by the hospitals receiving the money, and/or increase the Medicaid dollars to the public hospital system by reimbursing care at H+H at higher rates. It could institute a process by which private hospitals are required to invest in the public hospital system as a condition for receiving tax-exempt bonds for growth and expansion. Another option: Create a funding pool for Level 1 trauma centers supported by those hospitals that don’t offer the same and depend on H+H and other hospitals to maintain those costly operations.

While these may seem like pie-in-the sky suggestions, the NYSNA report points out where those steps have been taken nationwide. Take, for instance, California, where after San Francisco passed the Charity Care Ordinance of 2001, tying local approval of construction permits to demonstrative provisions of charity care, Sutter’s California Pacific Medical Center “had to promise $1.1 billion in concessions before the city would issue the required permits.” Among Sutter’s promises “were a freeze on prices charged to city employee’s insurance plans, operation of nearby safety net hospital, affordable housing investments and upgrading of nearby transit facilities and sidewalks.”

At the other end of the carrot-versus-stick spectrum, in 2015 a Morristown, New Jersey, judge revoked a local hospital’s nonprofit status – finding that the hospital behaved not like a charity, but like a business, the NYSNA report noted.

For its part, NYC H+H has already adopted more stringent measures, reducing staff, cutting new hires to 25 percent of open positions, eliminating redundant positions and closing facilities. With 70 percent of the system’s budget going to personnel costs, there is only so much retrenchment the hospital system can do without it affecting care, noted its administrators.

“As you are aware, New York City Health + Hospitals – the largest public health care provider in New York State” relies “significantly” on DSH and supplemental Medical payments, outgoing H+H CEO Stanley Brezenoff wrote on Sept. 29 to state Health Commissioner Howard Zucker, publicly requesting the release of the $380 million in matching federal-city dollars.

With one third of its operating budget supported by federal DSH payments and supplemental Medicaid dollars, any interruption in the flow of federal dollars would be disastrous for the state’s largest public hospital system, Brezenoff warned, adding: “The fact that the state has no financial stake in these payments only adds to the mystery of these delayed payments.”

3 thoughts on “Understanding New York’s Public Hospitals Crisis”

I work in the Lincoln ED. For lack of gauze I one used a SANITARY NAPKIN (Maxi Pad) to soak up blood from an oozing wound… the lack of supplies was dismissed by the administration saying, we routinely supply the ED with essential supplies. If gauze is not an essential supply in the ED, then either I’m an absolute moron, or someone is deeply misinformed? So I contacted our central supply coordinator, “the allotted gauze for the the week was supplied two days ago.” My response, “it’s not here. I have checked and others who stock our supply room have checked and there are no further supplies in our storage room. Can we please have some large 4×4 gauze?” I was told, “no there is NONE FOR US TO SUPPLY YOU WITH. “

Pingback: What Drives NYC’s Health Disparities? Health infrastructure in NYC – Hostos First Year Seminar

Pingback: Should Healthcare Be Considered a Basic Right in the United States? | The Candor