Abigail Savitch-Lew and Camille Padilla

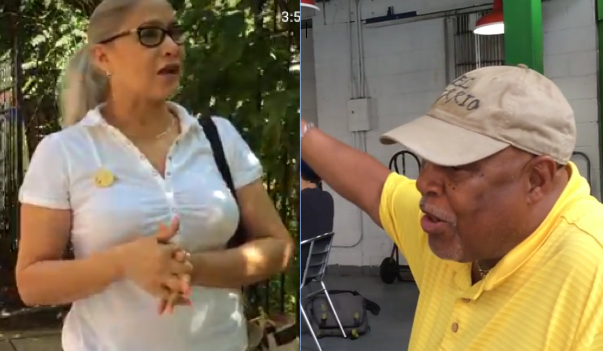

Azilde Plasencio, at left, and Robert Guilbe, at right, talk about the changes they've witnessed in East Harlem.

On Tuesday, the East Harlem Community Board will take a final vote on the city’s controversial rezoning plan for East Harlem.

It’s a crucial, if not decisive step of the multi-phase process through which a zoning plan is rejected or becomes law. In the months to come, Borough President Gale Brewer and the City Planning Commission will weigh in on the plan, followed by a binding vote by City Council.

The rezoning plan, proposed by the de Blasio administration in October, would allow for large increases in the allowable heights of buildings on several neighborhood avenues, encouraging the growth of market-rate housing and mandatory affordable housing, though some critics question whether those units will be sufficiently affordable for neighborhood residents. The plan would do other things as well, such as limit the size of buildings to preserve existing housing on certain blocks, while in other areas require developers to set aside space for transit infrastructure.

The administration says its plan closely mirrors the “East Harlem Neighborhood Plan,” created by local councilwoman Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and a steering committee of community organizations. But members of that steering committee—as well as the board’s Land Use Committee in its vote no with conditions on Friday—have objected that the city’s plan is far denser than the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan and lacks a number of needed strategies to prevent displacement, among other differences. Then there are other groups that don’t want to see any kind of rezoning at all—like the Movement for Justice in El Barrio, which is instead advocating for a 10-point plan to improve code enforcement in the neighborhood.

What’s unclear is how many East Harlem residents—particularly those who are less civically engaged due to family responsibilities, documentation status, and other barriers—actually know about these initiatives.

In a new collaboration between El Diario and City Limits, our reporters hit the streets and conducted about 20 video interviews with pedestrians and small business owners to determine what stakeholders know about the two zoning proposals as well as the Movement’s recommendations. We also conducted about 10 interviews off-camera with people who did not want to be recorded.

It’s too small a sample size to accurately project what the majority of residents know and think. Still, the interviews provide a small window into what East Harlem residents are saying about the plans outside of community meetings. Watch highlights from our interviews, and read our summary below.

A little more than half of the people we spoke to on video said had never heard of “rezoning plans” for El Barrio (and an even greater share of the off-camera interviews).

Of the other half, a few thought we were referring to the 2008 rezoning of 125th Street that is currently transforming that corridor or the administration’s plan to redevelop land owned by NYCHA. Some were vaguely or partially aware of rezoning efforts, and voiced concerns a rezoning would lead to gentrification and displacement.

“I’ve heard something about that,” said 57-year-old William Ortiz as he walked his dog. The 57-year-old Puerto Rican who was raised in El Barrio explained it was hard to follow-up on the details because he’s busy with work, his apartment, a dog, and taking care of his mother.

David, a 66-year-old African-American man who didn’t share his last name, admitted he didn’t know the details of any plans, but still had strong opinions.

“90 percent of the zoning plans for East Harlem are about corrupting the neighborhood,” he said. “Our neighborhood is becoming like an enclave for the rich and slowly but surely, everybody’s going to be pushed out—the poor, no matter what color. Is going to be pushed out, is going to be in the Bronx.”

A couple business owners asked us what kind of “zoning” we were referring to, and when we mentioned zoning that governs building heights, they made clear they were aware their block was being upzoned to allow higher buildings (the required mandatory inclusionary housing component did not come up).

Mohammed Maher, a business owner on a block of four- to five-story buildings on Third Avenue, noted that thanks to a prior rezoning in 2002, his landlord could already choose to demolish their building and build a 12-story building—so now rezoning again to allow 20-story buildings (or even 30 to 35 story buildings, depending on the site) didn’t seem to him like much of a difference.

“What’s approved is approved. If they want to keep El Barrio the same look they should have left everything the same. Not to go high or anything. To keep it unique: Spanish Harlem,” Maher said.

Whether they knew about the rezoning or not, many of the Latino and black residents interviewed feared they were getting kicked out. We were told about a rise of condominiums that were not affordable or sized appropriately for existing residents, about poor conditions in existing buildings, and about a case in which a resident suspected he’d been unable to get an apartment in a new building due to his Spanish last name. A couple residents were glad to see property values rising or the area growing safer, but were still concerned about displacement.

“The essence of El Barrio and Spanish Harlem is being erased because the ethnic groups are changing”, said Victor Cuevas, a 69-year-old Puerto Rican who moved to the neighborhood in 2001. The manager of a music store, Cuevas lives in rent-restricted housing and hadn’t heard of the rezoning plans.

East Harlem became known as Spanish Harlem in the 1930s after a migration from Latin America, especially Puerto Rico. When the area was practically ignored by the city, it was the Puerto Ricans in the area that brought it to life establishing businesses, botánicas (religious goods stores) and cleaning up empty lots to create community gardens that still exist today.

In the late 60’s and 70’s the Young Lords’ activism demanded the city’s attention, most notably, by sweeping the garbage on the sidewalk to the streets of El Barrio, forcing the Department of Sanitation to clean the abandoned area.

It’s true that today, the neighborhood’s demographics are shifting. Since 2000, the share of El Barrio that is white or Asian has grown from 10 percent to nearly 20 percent. Two newcomers to the neighborhood gave high reviews of the neighborhood’s affordability and convenience.

“I actually love the area here. People are really nice, people are nicer here I find, and there’s a lot going on. The bustle is cool, and also the rents are cheaper here,” said 27-year-old Kaleb Jordan from Colorado, who had recently moved from the Upper West Side after his landlord increased the rent. He hadn’t heard of the rezoning efforts, but he noticed that there were already big changes taking place on 125th Street.

“Seems useful that there are more resources coming in,” he said of the neighborhood’s change, adding, “I don’t know how useful they are to the people who actually live here, necessarily.” He said the neighborhood already had pharmacies and groceries, so it wasn’t like the soon-to-open Whole Foods would greatly improve his quality of life.

65-year-old Naiwen Wei had also not heard of the rezoning plans, but said that if the government wanted to allow taller buildings, that could help solve the city’s housing shortage.

Felipe García, an organizer with Movement for Justice in El Barrio, wasn’t surprised to hear that many residents hadn’t heard of the rezoning plans. He explained that the changes aren’t accessible to Spanish speakers because the community board meetings are in English and the city tends to post their plans on the internet, and he said that at the last community board meeting, members were told not to present their testimonies in both Spanish and English, though they eventually did.

(Community Board Chair Diane Collier partially disputed this characterization, saying that while it’s true most board meetings don’t have translation, recently they’ve tried to make an effort to provide translation at full board meetings related to the rezoning. The issue is not willingness, she argues, but cost, and at the last meeting translators were present but city translation equipment wasn’t available to the board because it was already in use elsewhere. Translation equipment will definitely be available at the June 20 vote, she said.)

To create their own 10-point housing plan, which is focused on improving outreach to tenants about their rights and more enforcement against negligent landlords, the Movement for Justice in El Barrio used other methods.

“We didn’t do outreach through social media because we know that’s not how the community acquires information. We knocked on doors, stood at train stations handing out flyers in the mornings and in the afternoon when people came back to work, and posted signs.”

According to Garcia, through their own outreach methods they reached about 8,000 residents. He stated that if the City wanted, they could educate more people with their resources.

“The Department of City Planning has been out in the community on East Harlem since planning began,” wrote Joe Marvilli, a spokesperson for the Department of City Planning, in an e-mail to City Limits. “In addition to attending most of the 40 visioning sessions and steering committee meetings, the Department participated in dozens of public and smaller group meetings on the proposal, before and during the public review process. There was also extensive coverage in dozens of newspaper articles and web posts, both in Spanish and English. We provided materials in English and Spanish as well to facilitate awareness and broader participation.”

“The East Harlem Neighborhood Plan process engaged an unprecedented cross-section of the community, hosting 8 public workshops and town hall meetings, all independently facilitated, with countless smaller subgroups meetings convened around 12 topics,” wrote Dorothy He, a spokesperson for Mark-Viverito. “The extensive community engagement was led by a Steering Committee comprised of 28 local community stakeholders, all with a long history serving the community. Never has a neighborhood planning process involved as many different residents and stakeholders in forming a community based vision for our future. We look forward to continuing that work and ensuring commitments are made that respond to our plan.”

A thank you to Rong Xiaoqing for proofreading Chinese translations.