Marc Bussanich

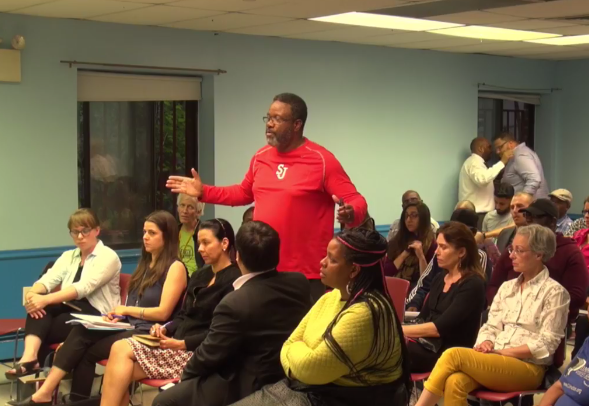

Leon Bligen, a local homeowner who said that despite the fact that he owns, he is concerned about the fate of his neighbors in East Harlem.

On Friday night, the East Harlem Community 11 Board Land Use Committee voted no to the city’s proposed rezoning of East Harlem unless the city agreed to satisfy a list of stipulations drafted by the board’s rezoning task force. That vote potentially sets the tone for the full board vote that will take place on Tuesday June 20.

It’s the first step in a longer process that will ultimately determine whether the city adopts the de Blasio administration’s proposal for East Harlem, which is one of about a dozen rezoning proposals or studies under consideration as part of the mayor’s affordable housing plan. East Harlem is the third neighborhood rezoning to enter the public review process so far: East New York was approved in 2016, and Far Rockaway is halfway through the process.

The committee’s stipulations in many ways echoed, and in other ways exceeded, the recommendations of the 2016 East Harlem Neighborhood Plan (ENHP) crafted by local councilmember Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, the community board and a team of community organizations.

The stipulations require any upzoning to follow the ENHP’s outline and be kept to the minimum needed to trigger the city’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy; the task force strongly objects to the higher densities in the city’s plan.

Highlights:

3:44 presentation by land-use consultant

25:34 questions from the public

59:00 presentation by the rezoning task force

1:20:00 committee begins formal consideration

1:27:45 roll-call vote

In addition, however, the task force says they won’t accept the current mandatory inclusionary housing policy requiring 20 to 30 percent of units be affordable. Rather, the task force says 50 percent of the housing on private land should be affordable, with 20 percent for families of three making no more than $25,770, and the other 30 percent for families of middle incomes making above $25,770 up to $103,080.

The stipulations also called for the adoption of some of the recommendations in the Movement for Justice In El Barrio’s ten-point plan.* Those include improved outreach to inform tenants of their rights and better enforcement of the housing code by improving inspection response times, promptly fining landlords, providing adequate follow-up to repair problems, and other recommendations.

The rezoning task force also called for a certification of no harassment program, adequate funding for workforce development, that when the city seeks to redevelop public land it works with nonprofits and commits to 100 percent rent-restricted housing, that NYCHA residents be able to sign off on any potential redevelopments of NYCHA land, and many other recommendations. The land use committee added another recommendation—the promotion of affordable homeownership opportunities—before adopting the stipulations.

The vote of seven disapprovals and two abstentions followed impassioned pleas from many members of the attending public to scrap the city’s rezoning efforts.

“My proposal to the board is to shut it all down,” said Leon Bligen, a local homeowner who said that despite the fact that he owns, he is concerned about the fate of his neighbors in East Harlem. “The affordable housing that is going to be put in place is only a small percent of the total apartments.”

“I keep asking, where the hell do I fit in?” asked Cecelia Grant, explaining that she is street homeless and has lived in El Barrio since the 1970s. “How many people are going to be displaced, and how many homeless people are you going to place?”

“You don’t have to say yes with conditions—you can say no,” said East Harlem Preservation’s Marina Ortiz.

A representative from the New York Academy of Medicine shared the organization’s conclusion that the city’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) makes a “significant underestimation” of the potential impacts of the rezoning on neighborhood health, mainly because the plan underestimates the potential for displacement, which can itself have a variety of health consequences. (The DEIS predicts only 27 residents will be directly displaced by demolition, and argues that the rezoning will not exacerbate indirect displacement associated with rising rents.)

After the committee’s vote, there were shouts of relief from the audience and, in stark contrast to the protests that have ended so many recent meetings, warm exchanges of goodnight between rezoning critics and members of the community board.

“I’m really pleased and pleasantly surprised,” said Ortiz, but she added that East Harlem should be entitled to anti-displacement strategies with or without a rezoning, and was concerned the city would promise investments—without any legal, binding mechanisms—as “tradeoff” in exchange for a zoning that lead to gentrification. She has long opposed a rezoning of any kind.

What exactly the de Blasio administration will offer East Harlem in order to get its rezoning approved—and what Mark-Viverito will be willing to accept—remain to be seen.

The full community board will hold a public hearing and vote on Tuesday June 20, 6:30 pm at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Goldwurm Auditorium, 1425 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10029. Capacity is limited to 200 people, so the board instructs the public to arrive early.

Next, Borough President Gale Brewer will hold a hearing, likely to be held on Thursday July 13, 6:30 pm at the Silberman School of Social Work, 2180 3rd Avenue, New York, NY 10035.

*Clarification: Some, but not all, of the Movement for Justice in El Barrio’s demands were incorporated into the rezoning task force’s recommendations.

2 thoughts on “East Harlem Committee Rejects Current de Blasio Rezoning Plan”

Just let us live in peace.. This is just a ploy to sneak in families who are in a higher income bracket .. Who in the long run will kick the lower income people out that live in El Barrio (this us) / East Harlem, either buying us out… Then where does that leave us that have been in this neighborhood all our lives? It is hard now trying to find a good place to live which we can afford. LEAVE US ALONE!

Pingback: How Harlem residents found a unique way to fight gentrification