Brooklyn DA

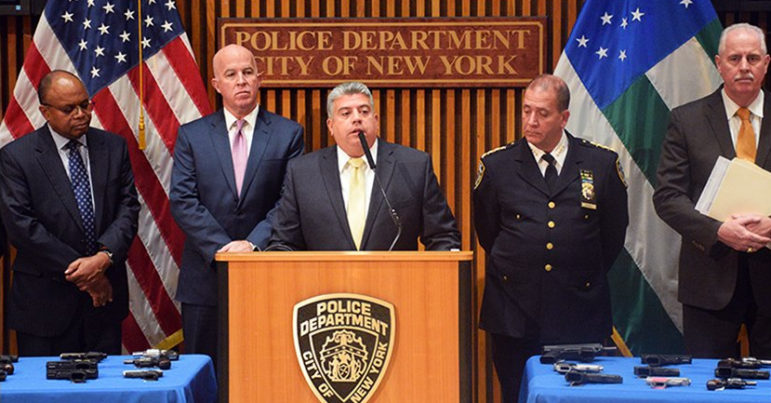

In October, Acting Brooklyn DA Eric Gonzalez and NYPD Commissioner James O’Neill announced indictments related to a plot to smuggle 40 guns to Brooklyn from South Carolina.

A&K Firearms in Midlothian, Va., just 20 minutes off I-95, isn’t shy about advertising what it does, which is sell guns. Back in December, the store’s Facebook page nudged customers: “Time is running out until Christmas Eve. Still looking for the right gift for that special someone? Hit us up.” It suggested as stocking-stuffers a .223-caliber rifle for $545, an EAA 9mm handgun with charcoal grey finish for $299 or a Springfield pistol that comes with not one but two magazines for just $399.

According to data released by New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman last fall, Virginia was the leading state of origin for crime guns recovered in the Bronx from 2010 through 2015. Ninety-one percent of the 6,197 guns recovered in the Bronx over that period for which trace data was available came from states other than New York; about one in nine of those Bronx guns came from Virginia. Pennsylvania ranked No. 2, just ahead of New York State guns. Florida, North Carolina and Georgia rounded out the top six states.

Only Brooklyn saw more guns recovered over the 2010-2015 span (9,447) than the Bronx but no other borough saw as high a share of its weaponry come from out of state. In a single Bronx ZIP code—10457, which covers Belmont and parts of Claremont Village—492 guns were recovered, 50 of them from Virginia, according to the AG’s numbers.

Data shrouded by law

Curious about what gun sellers thought about the complaints in New York about out-of-state firearms, City Limits contacted five high-profile gun stores in each of the top five sources of out-of-state guns in the Bronx. A&K was the only one to get on the phone. “Hey man,” the man who picked up there said, “I don’t feel comfortable answering none of your f—in’ questions” and quickly terminated the phone call.

One important note: There’s absolutely no available evidence to suggest that even a single gun from A&K has ever ended up in New York City—because there’s no public evidence, period, when it comes to the exact origin of crime guns.

Under an amendment to Justice Department spending bills that Republican Kansas Congressman Todd Tiahrt authored beginning in 2003, the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives is, according to the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, prohibited “from releasing firearm trace data for use by cities, states, researchers, litigants and members of the public.”

That trace data is imperfect — not all recovered guns are actually used in crimes or submitted for tracing, and not all guns can be fully traced. Of the 53,000 trace reports the NYAG studied, the date of first purchase was unattainable in 42 percent of cases.

But accuracy might not have been the gun lobby’s chief reason for backing the Tiahrt Amendment. The Natonal Rifle Association celebrates the now permanent Tiahrt rule on its website by bemoaning the bad old days when “cities and anti-gun organizations sought access to confidential law enforcement data on firearms traces, both for use in lawsuits against the firearms industry and for use in questionable studies used to support their goals.”

Sure enough, asked if the New York attorney general’s office could tell us more about where the guns that ended up in the Bronx came from, a spokeswoman there wrote: “Federal restrictions on data prevent that level of detail from being made public, unfortunately.”

Gun trafficking: Origins are murky

But federal restrictions aren’t the only reasons why, despite the increasing emphasis on gun trafficking as a law enforcement priority, there seems less discussion nowadays about points of origin for guns that threaten or hurt New Yorkers.

In 2006, Mayor Bloomberg sent undercover investigators to stores in five states and gathered evidence the he said demonstrated that 27 of those firms had turned a blind eye to obvious straw buyers—people who buy a gun for someone who can’t because he or she might not pass the background check. The mayor sued the stores and settled with many of them, winning promises of reform. The mayor later targeted gun shows for a similar probe.

More recently, gun sellers have not been subjected to that harsh spotlight. Even when New York prosecutors go after an alleged gun trafficker for smuggling firearms to New York, little is said about the businesses where these guns originate.

In December, Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance announced the arrest of men involved in an alleged Virginia-to-New York smuggling ring. The leader allegedly bought 86 guns from two co-conspirators in Virginia who, the DA’s press release said, “purchased the weapons from local firearms dealers – at times using straw purchasers.” The release didn’t name the stores, however, and a spokeswoman for the DA told City Limits last week that because the name of those stores hadn’t been mentioned in any filings associated with the case, she could not disclose it.

Asked about an alleged smuggling ring busted in July, the Bronx district attorney didn’t respond to questions about where in Pennsylvania and Texas the guns that were part of that plot allegedly came from.

Meanwhile, the Brooklyn DA has prosecuted at least three separate sets of alleged gun traffickers over the past 18 months. One involved a man who planned to run 40 guns from South Carolina to the five boroughs. In a second case, Delta Airlines employees were involved in allegedly smuggling 153 guns from Georgia. Yet another case alleged that eight people conspired to smuggle guns purchased in the Atlanta and Pittsburg areas to the city.

Asked if prosecutors had information in any of the three cases about where the guns originated, a spokesman said the information wasn’t in the indictments and was unavailable.

Press coverage from a separate federal trial related to the Pittsburg case indicates that some of the guns were allegedly purchased at Gander Mountain—a national sporting goods chain—and Anthony Arms, a gun shop located just a mile from one of the Gander stores in the Pittsburgh area. Evidence presented in the Pittsburgh case suggests the defendant paid straw buyers to purchase the guns that he then trafficked to New York City. There’s no suggestion of any complicity by the stores involved in that case.

Information on where guns come from isn’t the only gun data that’s become harder to get. New York State also now permits gun owners to shield themselves from freedom of information laws. “Most public records ought to be open,” Ken Bunting, executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition, said in 2013, when that FOIL exemption was authorized. “Unfortunately, most open government laws have restrictions and are ill advised, and I suspect this is another one.”

This article was reported by members of the City Limits Fall 2016 Bronx Investigative Internship Program. Click here to see other journalism produced by that initiative.