Michael Vadon

Sen. Sanders' results at the polls in Tuesday's primary seemed to fall short of what his huge crowds predicted. Was that because of a voter-list purge, or because NY's laws are poorly suited to accept latecomers into the process?

The controversial removal of names from the voter rolls in Brooklyn before Tuesday’s presidential primary cut across party lines and was far larger than the changes seen in other boroughs, a City Limits review of enrollment data finds.

While larger shifts—both gains and losses—in registration numbers have been seen over the past eight years than occurred in Brooklyn in 2016, the net result of changes to the Brooklyn rolls during the past two annual cycles has been to erase the huge registration gains seen in the last presidential and mayoral races.

Both the state attorney general and the city comptroller have said they will investigate the changes in the voter rolls. It is not uncommon for the Board of Elections to periodically remove duplicate names and other invalid registrations from the voter list. But the size of the reduction in Brooklyn’s numbers, in a presidential election year, has raised questions.

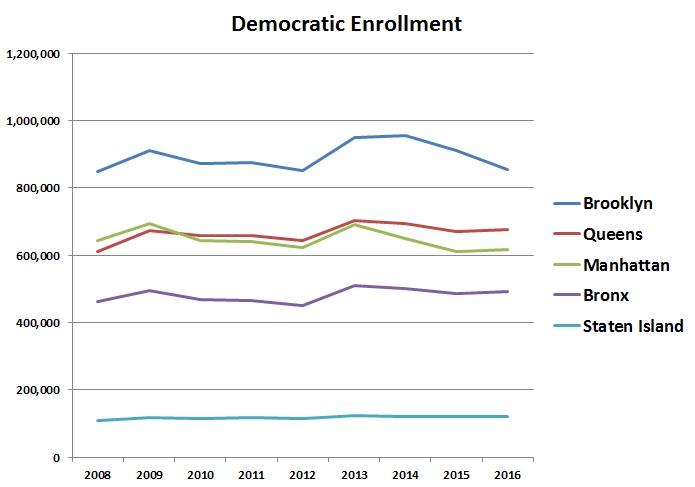

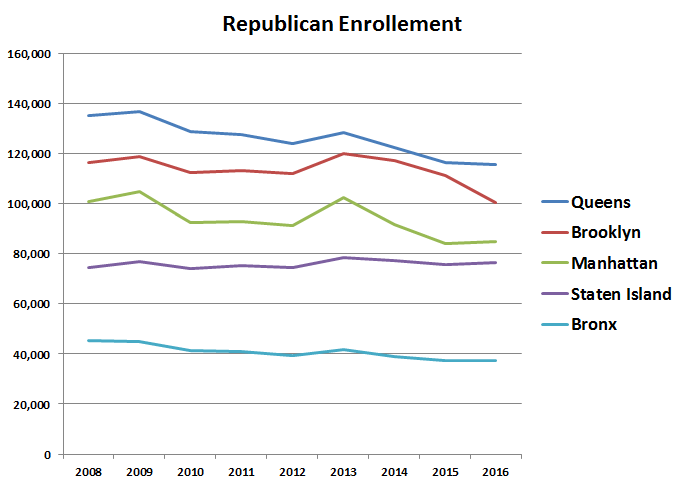

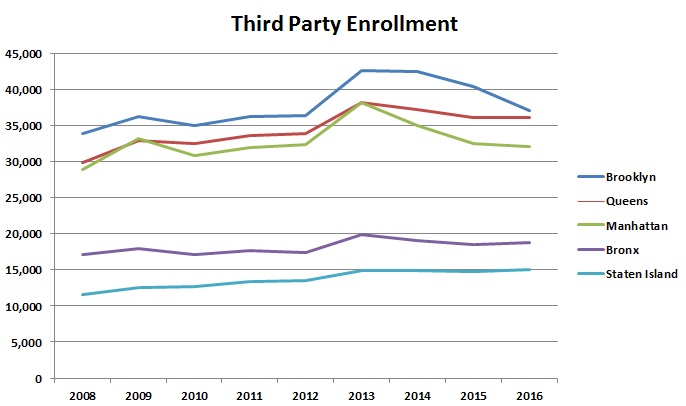

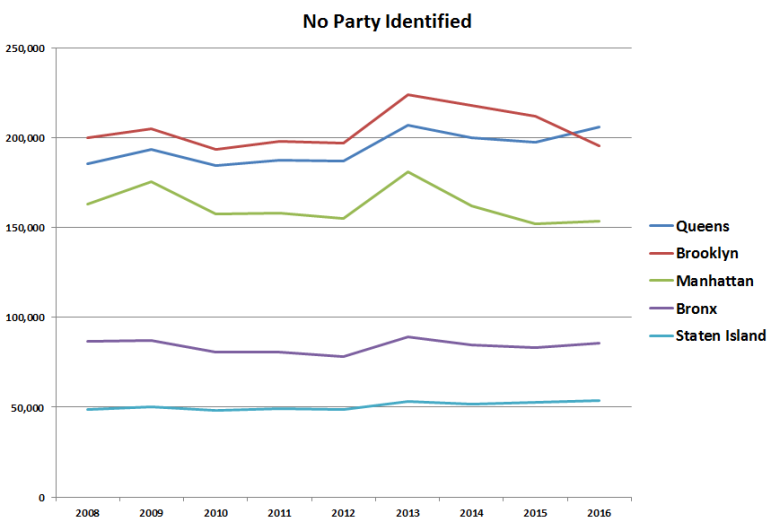

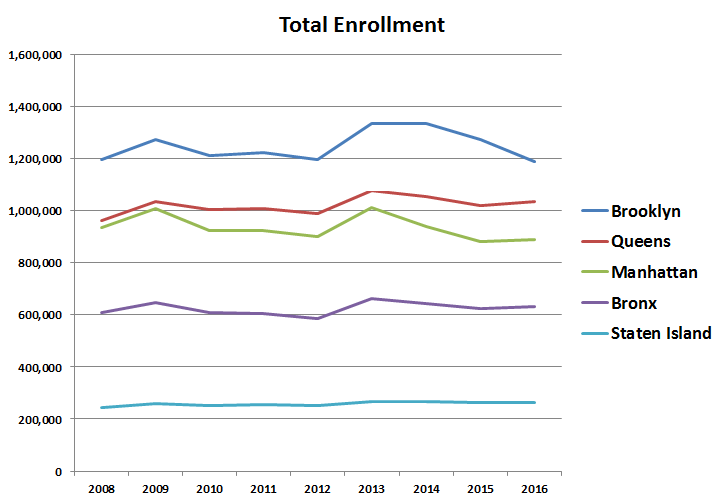

The New York State Board of Elections releases updates to its enrollment counts twice a year, in November and in either March or April. Looking at the March or April tallies of active voters from 2008 through this year, one sees a logical pattern: Registration numbers rise from 2008 to 2009—likely because of the presidential election—and then slip, before rising again in the next presidential cycle in 2012. In each borough, the numbers then start to fall.

What’s surprising is the size of the fall-off in two boroughs. Across 2014 and 2015, Manhattan shaved more than 12 percent off its rolls. In Brooklyn, the change from 2015 to 2016 was multi-partisan: Democratic enrollment fell 6 percent, Republican registration more than 9 percent. The number of Brooklyn voters registered with third parties dropped 8.5 percent, and the number of Brooklynites registered with no party affiliation slipped 7.8 percent.

The net result is that from 2012 to 2016, total voter enrollment in Manhattan actually shrunk by 1.34 percent: In other words, all the increase from 2012 was reversed, and then some. Brooklyn’s active voting population is 0.89 percent lower than it was in 2012.

But enrollment in Queens grew 4.6 percent, Staten Island’s increased by 5.4 percent and the Bronx saw 8.3 percent growth. One consequence of these changes: Brooklyn’s voter pool is now a slightly smaller share of the overall city electorate—29.6 percent in 2016 versus 31.4 percent in 2015.