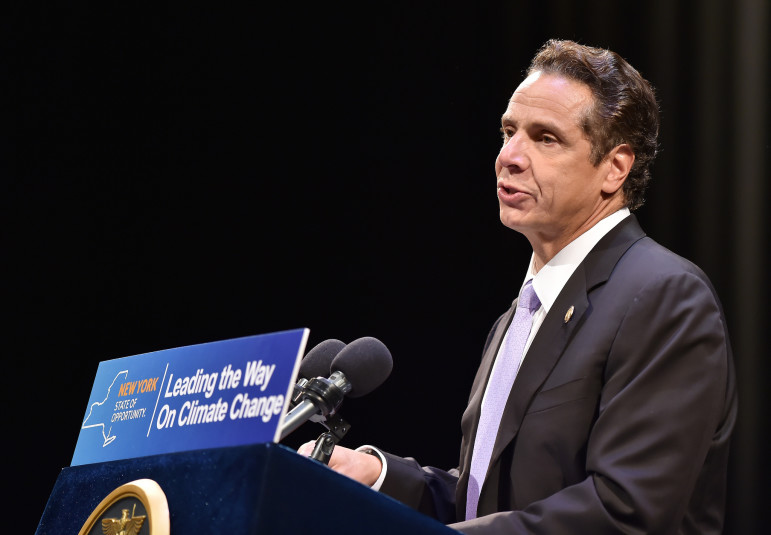

Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of the Governor

Gov. Cuomo has set ambitious environmental goals and launched a broad remake of state energy policy to achieve them. But it's not yet clear how the costs and benefits of the moves will affect low-income households.

After months of discussion, state energy officials last week approved a new fund for clean-energy projects in New York—part of an ambitious effort by the Cuomo administration to remake the way power is generated, distributed and paid for.

Even if it has eluded much coverage in the mainstream press, insiders have noticed the breadth and boldness of Gov. Cuomo’s energy plans. An energy industry blog has said that “New York is arguably taking the most ambitious, comprehensive approach to utility market reform,” and GreenTechMedia.com once called it “the country’s most ambitious statewide grid-edge reform.”

Some advocates, however, worry that the brave new future of electricity in the Empire State could leave low-income New Yorkers behind.

Earlier this week, a City Limits investigation of an earlier clean-energy program found that it had fallen well short of expectations. Launched during the administration of Gov. David Paterson, Green Jobs/Green New York aimed to retrofit tens of thousands of homes, create thousands of jobs and help low-income households participate in large numbers, but its performance didn’t match initial hopes.

Cuomo launched his own initiative, called Reforming the Energy Vision, in 2014. It dovetails with the governor’s goals for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions and increasing the role of renewable energy in New York. REV is supposed to help businesses and households reach those environmental targets while also creating jobs and reducing the state’s high electricity rates.

New world, old grid

The idea behind REV is that the challenge of climate change and innovations in how power is generated are a bad fit for the way New Yorkers pay for electricity. Nowadays, customers with solar panels may sell energy back to a grid designed to send power in the other direction. Reduced electricity usage, while a boon to the environment, poses a problem for utility companies whose revenue comes from usage fees. And much of the high cost of electricity in New York is blamed on a big gap between the average need for power and peak demand, because the costly infrastructure needed to meet peak demand has to be supported even though it’s usually not needed. There’s probably a technological solution to that, but the market for such a fix has yet to develop.

“It is calling into question the old utility model,” Anthony Giancatarino, the director of policy and strategy at the Center for Social Inclusion, says of REV .”Can we really get carbon emissions down, can we really get affordability, can we really be investing in renewable energy with an antiquated system?”

REV is supposed to make it easier for utilities, customers, investors, inventors and others to react to those challenges. One part of the vision involves rewriting regulations for utilities. Another aims to reduce demand by customers of the New York Power Authority, which generates power used by public entities like the MTA, Port Authority and NYCHA.

The final piece is the Clean Energy Fund, which was okayed last week by the state’s Public Service Commission. CEF aims to develop a market to support the changes the state’s energy system needs. It includes NY-Sun, which offers solar-energy investments, and the NY Green Bank, which is supposed to leverage private investment in clean energy. There’s also a market development fund and a pool of money for innovation and research. All told, the fund is supposed to spend $5 billion over 10 years. According to the governor’s office, it should save consumers $39 billion over that period.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority will oversee the Clean Energy Fund, which takes over most of the work that was part of the Green Jobs/Green New York Program. Back in 2009, predictions were that the initiative would create 14,000 jobs and lead to retrofits a million homes, but it appears just over 1,000 jobs and around 30,000 retrofits were generated.

Green Jobs was credited with achieving savings for some customers and pioneering new financing mechanisms for clean power. City Limits found, however, that underwriting criteria made it hard for some low-income households to qualify for loans under Green Jobs/Green New York. A complex application process, disparities in the cost of living, fundamental repair needs in some homes, and the way the program sized up costs and benefits also slowed the program down.

The biggest barrier, advocates for low-income people said, was that poor people were reluctant to take on new debt to pay for retrofits.

Lessons learned?

NYSERDA did not make a representative available for an interview, so it’s not clear whether the agency believes the Green Jobs experience offered any lessons for designing the Clean Energy Fund. But there are signals that the authority now better grasps the unique challenges of serving poorer New Yorkers. “[Low- and moderate-income] residents are financially stressed, and lack the capital or willingness to take on debt to cover energy efficiency and distributed generation investments, despite the attractive economic value of these investments,” NYSERDA wrote in documents during the approval process for the Fund. In announcing the Fund last week, the governor’s office noted that “At least $234.5 million must be invested in initiatives that benefit low-to-moderate income New Yorkers during the first three years.”

Advocates had pushed for a larger share to be earmarked for lower-income households, but feel they achieved a victory in getting nearly $80 million a year set aside through 2018.

Exactly what that help will look like is uncertain, however, because NYSERDA is still drafting several parts of the plan, including the one pertaining to low- and moderate-income households.

The concern, says Jessica Azulay, program director at Alliance for a Green Economy, is that for all its interest in innovation, the Clean Energy Fund still relies primarily on the market to deliver cheaper, cleaner power to New Yorkers.

“I’m very skeptical of that,” she says. “The markets tend to favor people with money. They tend to favor businesses that already have advantages. What will the opportunity really be for low- and moderate-income people in New York? If the opportunity is being able to be an energy producer yourself, or better manage your demand [through use of technology], people who can’t afford those are potentially going to be left behind.”

REV will probably generate great ideas, Azulay says—like devices that, without any help from the consumer, get his washing machine and dryer to run at times of day when power demand is low—but in a market environment, those tools will come with a price-tag that could be beyond some consumers’ means.

And that’s just for the selling that’s legit. There’s also the threat of scams that prey on the poor. “Without really strong market protect there’s an opportunity for predatory marketing,” Azulay says.

Given how important REV and the Clean Energy Fund will be to the state’s environmental and economic future, the lack of public awareness is a problem. The obscurity is partly a result, no doubt, of how technically complex the topic can get. But Giancatarino believes state government has failed to keep New Yorkers informed and involved: “They need to do a better job engaging the public.”

It’s a discussion, he adds, that should be about not just electric power, but social power as well. Given gaping inequality in New York, “We can’t talk about changing the grid and not have vastly different social outcomes,” he says. “This is transformative and you’re missing an opportunity to really think about economics.”

One thought on “Will New Cuomo Energy Fund Help or Hinder Low-Income New Yorkers?”

So who exactly is this alliance you used as a source Jarrett? Because city limits as you might recall wrote jibberish on the Rockaway pipeline draft eis because your reporter used bad sources.

Just the groups twitter feed alone makes me question the validity of information they provide. https://mobile.twitter.com/agreenewyork