Adi Talwar

Sixth-grade teachers (clockwise from bottom right) Lalaina Andriananjason, Nancy Dooley, Yesenia Morel and Tariq Hussein, conducting a Grade Team Meeting at CHAH. While not on the Renewal Schools list, CHAH uses many of the techniques that the de Blasio administration wants to apply to failing schools.

It’s 8:30 in the morning on a Thursday in mid-May and five 6th grade teachers and a social work intern are sitting around talking in a classroom in a small public school in Washington Heights. They are not chewing the fat or comparing their plans for the weekend. Instead, they are examining the essays of two students they all share, as a way into discussing how sixth-graders Lawrence and Denise are doing, and what their teachers should be doing with them.

They talk about how to push the high achieving boy past where he is now and how to support the girl, a shy English Language Learner who still struggles with English vocabulary and academic language. The discussion moves around the table from English teacher to science teacher to math teacher to social studies teacher to ESL teacher and back with ease. They have done this often—in fact, every week since September.

Later in the day, two other teachers meet in a quiet office. Rosa Lopez, an 11-year veteran English teacher, is the coach to the other, Michael King, a history teacher. They discuss how he might open up a lesson on the Truman Doctrine and the U.S.’s policy of containment of the Soviet Union. It works well in one class, but less so in the class of second-language students. They sit around King’s laptop, which displays the cartoon, a video clip and a document he plans to use. Why not have the students examine the political cartoon first, give them some time to figure it out, Lopez suggests, and discuss it, then go into the lesson? He explains how this one lesson will be revisited when the class gets to the Korean and Vietnam wars and students will debate the effectiveness of this policy. He says he’ll try her suggestion later that day in his class.

King is not a “newbie,” but someone who has been teaching for six years. Like all the teachers we spoke to at the Community Health Academy of the Heights (CHAH), he is constantly working on his craft.

These are scenes at what the New York State Education Department has called a “failing school,” because its students had low scores on the eighth-grade math and English tests. A small public 6-12 school on W. 158th Street, CHAH has an overwhelmingly Latino student body and nearly a third of its students are English language learners. Nine out of ten students are considered economically disadvantaged, and one in six receives special education services.

It is the kind of school at the center of Mayor Bill de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña’s initiative to turn around low-performing schools. The grade-level teams and the coaching, along with Saturday tutoring, are all pieces of a complex jigsaw puzzle of approaches that CHAH has been using to improve itself. In many ways, it is a model for what Fariña and the Department of Education is rolling out slowly but persistently across the city.

How to fix failing schools has been on the New York City Department of Education’s agenda for 20 years, when an angry op-ed by an activist minister in East New York described educational “dead zones,” where schools in impoverished neighborhoods had been failing generations of students. Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s approach was to close down large failing high schools and open four or five new ones in the same buildings, often with different teachers and students. De Blasio’s approach is to “renew” them, to try to turn them around with some of the down-on-the-ground approaches that are also used at CHAH.

In early June, CHAH was removed from the State’s list of Priority schools. The de Blasio and Fariña DOE is hoping that their individualized plans to remake schools will be more effective than Bloomberg’s approach of shuttering and reopening new schools and will get the results that CHAH has.

De Blasio ran for mayor as the anti-Bloomberg, particularly so in his education policy. He appointed Fariña, a long-time teacher, principal and superintendent to be his schools chancellor, a contrast to Bloomberg’s longest-serving chancellor, the lawyer and corporate executive Joel Klein. Instead of the scores of MBAs and consultants who staffed the Department of Education under Bloomberg, Farina has hired long-term educators like herself to be superintendents and ruled that no one can become a principal unless they have taught for least seven years.

Last November, with some fanfare, de Blasio announced what he called the School Renewal Program, a $150 million initiative to overhaul 94 low performing schools. “We believe in strong public schools for every child,” he said. “Getting there means moving beyond the old playbook and investing the time, energy and resources to partner with communities and turn struggling schools around. We are going to lift up students at nearly one hundred of our most challenged schools. We’ll give them the tools, the leadership and the support they need to succeed and we’ll hold them accountable for delivering higher achievement.”

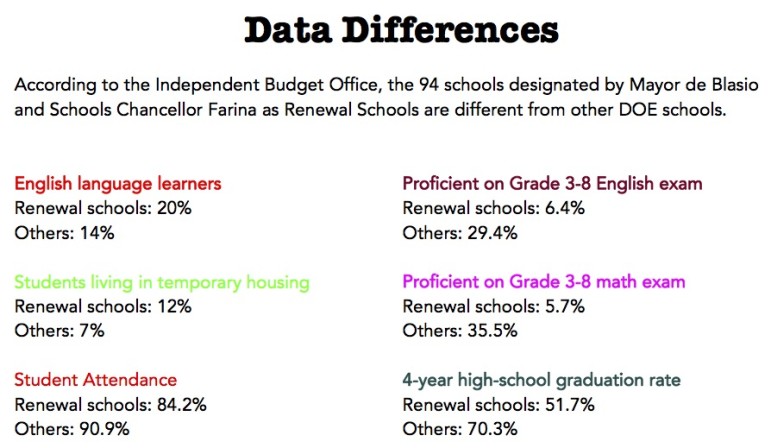

On

As a group, the demographics for the Renewal Schools tell a big part of the story. All principals at Renewal Schools have been provided coaches—long-time successful principals—who give advice on everything from staffing to curriculum to budgeting. Each school will add one hour of learning time each day, an expanded school year and a week of professional development over the summer as well as training during the year in new curricula in literacy and mathematics, how to use a newly established data system, how to integrate the community school model into schools and a variety of other topics.

All Renewal Schools will become “Community Schools”, which means community based organizations will bring in a variety of services including health, dental and mental health services to provide support services for the students. While the New York Times and others have said that community schools—Cincinnati is the best known system to use them—don’t by themselves spur achievement, Fariña and others say that providing schools with these services helps them deal with issues that prevent students from learning, as part of a larger package including reworking curriculum and providing professional development for teachers. At CHAH, which has had an associated health clinic since it opened, when all of its students were given an eye test, 40 percent failed and have been referred for glasses.

Fariña’s DOE has a different world view than infused the DOE during the 12 years of the Bloomberg Administration. Hooking onto the small schools model, which had long been espoused a part of the solution to “factory model high schools,” as the single panacea for long-time failing schools, Bloomberg’s DOE used it as a cudgel to break up neighborhood high schools and expand charter schools. It became a one-size-fits-all solution to a multi-faceted problem. De Blasio and Fariña’s DOE is trying to individualize remedies.

What has happened in the seven months since de Blasio’s speech is a collection of initiatives, some at least partially up and running in some schools, while others are still at the very beginning stages.

The last week of May, the DOE released a new set of benchmarks to be used at each school to assess improvement. Each school will work with the DOE to create an individualized “benchmarks menu” which lays out what is expected of them. Each school has to raise attendance rates. Others, the schools choose. Some of the measures are more qualitative, like effective school leadership, rigorous instruction and strong family-community ties. The schools then select three more data-driven benchmarks like test scores or graduation rate and are given a degree of improvement they must achieve.

Transforming a school is a complicated process because schools are complex organisms. It requires making a school safe, reorienting the students with higher expectations and acclimating them to a “college going culture” and providing support services but also helping to develop teachers as well. Some teachers are new and still have a lot to learn; others have been teaching a long time and need to refresh their craft. Many are used to working on their own, closing the door to their classroom and trying to figure out things by themselves.

It is just some of these issues that the principal and teachers at CHAH are taking on. The school was established 10 years ago with a partnership with a 60-year old community based organization, the Community League of the Heights. It began in two dilapidated buildings in Washington Heights, and a year ago it moved into a $52 million six-story building on west 158th Street. Mark House, mid-sized with a shaved head, a veteran teacher and assistant principal, became principal in 2011.

House, energetic but also endlessly calm, has thought long and hard about teaching. “There’s a notion in charter schools that ‘anyone can do this job.’ That’s not true. My mother was a teacher for 33 years and we saw how hard she worked,” he said. “Then there are these people who feel that good teachers are born. Sure there are certain personality types that help you in teaching. But most of the craft is learned and if it is learned, it takes time.”

Every teacher in the school has a coach who meets with them to discuss their teaching. House himself teaches a 7th grade social studies class. “It keeps me honest,” he says. Teachers have observed and critiqued him.

And yes, he has “counseled out” a couple of teachers, suggesting that this may not be the profession for them. This is an approach he shares with Fariña, who did that when she was a principal. Not everyone can be a teacher.

But this is a very different take on teacher quality than that underlying the current pitched battle over what percentage of the teacher evaluations should consist of their students’ scores on the high stakes tests that have been causing so much fracas in New York State. Currently 40 percent of teachers’ evaluation is based on their students’ tests. Cuomo in his State of the State speech called for it to be increased to 50 percent. Michael Bloomberg, in a speech at MIT said, “If I had the ability to just design the system … you would cut the number of teachers in half and weed out all the bad ones.”

At CHAH, the focus instead is on teacher development. As a group, they read and discuss books, for example, Mindset by Carol Dweck, a Stanford University psychologist. Dweck makes the point that many kids buy into the notion that intelligence is a given—you either have it or you don’t—and that leads to them not put in the work necessary to do well. “If kids feel that their talents are fixed, they have a hard set of attitudes about learning,” says House. “Teachers need to open students’ eyes. We spent some time reading it and thinking about what are the implications for practice.”

For 6th and 7th graders, CHAH has created separate English and writing classes, to give them more time to work on their writing. They have “looped” some grades, keeping students with the same English, social studies or math teachers for two years to maintain continuity. They’ve expanded their Spanish-language offerings for three levels of students (those who are fluent in Spanish in both writing and reading, those who can communicate verbally but are working on becoming literate and those who have almost no Spanish).

Principal Mark House has 'counseled out' a couple of teachers, suggesting that this may not be the profession for them. This is an approach he shares with Fariña, who did that when she was a principal.

But not everything is about helping kids catch up. As a school with an emphasis on health and science, all students take biology, chemistry and physics. The physics teacher, Shira Korn, a tall woman with a dramatic presence, pushes students to deconstruct the problems before they start to solve them. She has found herself marking physics Regents with teachers from Stuyvesant and Bronx Science, two schools with very different reputations and student bodies. The 6th grade students just came back from a three-day camping trip in Massachusetts, many of them away from their families for the first time, where they participated in building houses for the camp, encountered wildlife they had never seen before and debated questions like whether human beings should interfere with nature.

All of these changes are part of what is called “building capacity,” which is at the heart of what Fariña is trying to do on a systemic level, particularly in the Renewal Schools, that over a long period of time have not been working. Michael Fullen, a professor emeritus at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto has written extensively about urban education and district-wide change. “Capacity building is not just knowing what successful schools are doing,” he wrote in Big-City School Reforms: Lessons from New York, Toronto and London, which critiqued the reforms under Bloomberg as well as those in other cities. “You actually have to be helped to develop the competencies individually and as a group.”

He and his co-author Alan Boyle discuss what they call push and pull factors in making school change. Bloomberg got high marks on the push factors, but ignored the pull ones, like reaching out to the school staff to create a common strategy, developing their professional abilities and working on sustainability.

“Bloomberg had a scorched earth policy,” says Fullen, from California where he is working with a number of school systems around the state. “Bad people left and good people too. He killed the grass as well as the weeds.”

Building capacity is not easy. At Richmond Hill High School, a Renewal School in Queens, there has been a bit of push back. In mid-May, an anonymous letter appeared in teachers’ mailboxes and was left in the library for students to see. It was written by a couple of disgruntled teachers angry with some of the changes that Neil Ganesh, the second-year principal, has tried. Chalkbeat interviewed 20 staffers and students and found a “more complicated situation than the one portrayed in the letter … where discipline problems remain…but where new policies are showing promise and a sense of hope for the school’s future is sprouting.”

Flushing High School, also in Queens, is on its 5th principal in five years and he is retiring at the end of the year. But lead English teacher Katie Ottaviani is hopeful. She has taught for 17 years—first in Florida, then in Maryland and now for the last four years at Flushing. She has been working with other teachers–history, science, English and math–in the 9th grade academy around the Writing Through Thinking Through Strategic Inquiry program since February. This is a “writing across the curriculum” program, where each teacher is expected to get students to write in their class, which they then examine as a group. Twice a week, the 9th grade teachers look at student writing on a microscopic level—down to the sentences.

“There was so much pushback in the beginning, even anger,” said Ottaviani. “The teachers felt they had to step back from teaching their own content to teaching writing.” They each worked on teaching students how to take notes on their reading, helping them to absorb the material. And because the teachers were working consistently across all of the students’ classes, students’ writing improved. And by looking at how students expressed their ideas about osmosis or the Sudanese war, it became clear when students were not understanding the subject matter.

Now the initial naysayers are participating. Ottaviani says. “From teaching these writing strategies, it’s like planting a seed,” said Ottaviani. “It’s growing teacher practice and students’ ability.”

This is what growing school capacity—both teachers’ and students’—looks like. This is the nitty gritty of school renewal that de Blasio and Fariña are betting on. It is uncertain that substantial evidence on the value of their approach will emerge in time for Cuomo and the state legislature’s next evaluation of mayoral control, and it’s unknown what the new state commissioner of education thinks is the best approach for saving schools.

Seeds are planted, shoots are coming. Now we wait.

2 thoughts on “De Blasio’s Education Agenda Takes Shape at Renewal Schools”

Great Article that highlights the great work CHAH does every day! For more on CHAH go to CHAH.NYC for “Our Story” or follow us on twitter @ CHAH_NYC

that’s school is so bad , the lunch is terrible they don’t let students have their phones . That’s unsafe what if there’s an emergency and they need to call the parents ! I don’t give a damn if they could call the parents no it’s unsafe 1 star