Yale Rosen

A TB patient's X-ray.

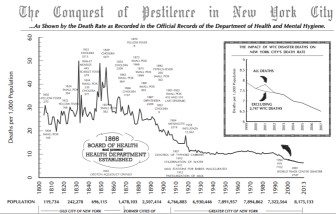

One of the best charts in the city is the one that graces the cover of the health department’s annual compendium of vital statistics. Grandly titled “The Conquest of Pestilence in New York City,” it maps the city’s general trend away from mass death due from preventable causes. Small pox, cholera and typhoid fever all did their damage but then faded—thanks to many factors, government action chief among them. It’s a helpful graphic to keep in mind when debate breaks out, whether about vaccines or circumcision rituals, pitting individual rights against sound public-health policy.

DOHMH

Some aspects of that ongoing public-vs.-private tension over health policy get little attention. One of them is Section 11.47 of the New York City Health Code which, according to the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, “authorizes the Commissioner of Health to exercise a range of compulsory options to control TB.” These include issuing an “isolation” order to forcibly detain infected people for several months so they can finish the prescribed course of medication. According to DOHMH, “There are currently three tuberculosis patients under an isolation order at Bellevue Hospital Center.”

TB is not a disease most New Yorkers think much about. It’s a highly contagious—according to the National Institutes of Health, “a person with an active case of TB will infect between 10 and 15 people a year”—bacterial infection that attacks the lungs but can spread to other parts of the body. It usually can be cured, but only with a tough regimen of meds.

As recently as 1977, there were 30,000 cases and nearly 3,000 deaths from TB every year in the U.S. In 2011, there were 10,000 cases and fewer than 600 deaths. In 1910, there were 30,000 cases of TB in New York City, and 10,000 people died from it. Last year there were 585 cases and 30 deaths. But those overall trends mask a bump in the latter part of the 20th century. As NIH puts it:

Around 1985, cases of TB began to rise in the United States. Several interrelated forces drove the resurgence, including increases in prison populations, homelessness, injection drug use, crowded housing, and increases in populations in long-term care facilities. Along with increased immigration of people from countries where TB is endemic, these forces provided ideal conditions for TB transmission. Adding the most fuel to the fire, however, were the HIV/AIDS epidemic and increases in multidrug-resistant TB.

Worldwide, it’s estimated that one in three people carry the TB bacteria, although most don’t actually get sick from it. Every second, someone gets infected with TB somewhere on the globe. Nine million new cases occurred in 2013, according to the World Health Organization, a third of them in India or China. And 1.5 million people died that year from TB, about a quarter of them HIV-positive. The World Health Organization estimates that 37 million TB deaths were prevented so far in the 21st century through better diagnosis and treatment, but in its annual report on TB WHO argues that”given that most deaths from TB are preventable, the death toll from the disease is still unacceptably high and efforts to combat it must be accelerated.”

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, in 2013, New York State had the fifth-highest rate of TB infections (with 872 cases) behind Alaska, Hawaii, California and Texas. While New York City’s level of deaths and infections has dropped dramatically still, DOHMH says the local infection rate is more than twice the national average. Some neighborhoods have infection rates that are extremely high, like Sunset Park, where the TB rate is more than three times the citywide average. Poverty is one factor in the prevalence of TB in the city, but so is New York’s role as a destination city: 85 percent of people diagnosed with TB are foreign-born, according to DOHMH.

The city employs a range of TB controls, including operating four “chest centers” that offer sophisticated testing and treatment. Service at the centers is free if you’ve symptoms or a positive test for TB.

And then there’s Section 11.47. It permits the city’s health commissioner to issue orders forcing a patient to be tested for TB, compelling an infected person to take medication, requiring someone to take their meds under direct observation, or detaining a patient in a hospital because they are likely to infect others or refuse to take their drugs. This last step “should generally be considered a measure of last resort,” the department’s TB handbook says.

A patient can challenge the commissioner’s order in court, and they get a city-appointed lawyer if they need one. Even if the patient doesn’t challenge the commissioner’s order, it’s only good for 60 days; after that, a court order is required, and it must be renewed every 90 days. To convince the court, DOHMH says it “must provide clear and convincing evidence that the continued presence in the community of the individual with active TB presents a danger to the public health and that there is no measure short of detention that can be reasonably applied.”

The justification for detaining someone to get TB medication is to make sure that person is treated and to prevent them from infecting others, DOHMH says, but also to “prevent the development of an epidemic of acquired drug resistance among TB patients who are unwilling or unable to adhere to an interrupted course of treatment.”

Some 12 to 15 isolation orders are issued every year in New York City, and most of those patients will be held for several months—although DOHMH says it releases them early if it can.

City Limits contacted leading civil liberties organizations to see if they’d mounted any challenges to detention orders in recent years, and no one said they had. According to DOHMH, “Most patients who are not adherent to treatment have significant substance abuse issues or mental health problems that are not being addressed,” so each isolated patient is provided with a social worker to try to address those deeper issues. When a lung disease that’s killed people since the days of ancient Egypt isn’t your biggest problem, perhaps a few months under constant medical supervision isn’t the worst thing.

One thought on “UrbaNERD: A No-Nonsense Tool in the Fight Against Tuberculosis”

Pingback: Tuberculosis: UrbaNERD A No-Nonsense Tool in the Fight Against Tuberculosis | Bread Of Life