City Planning

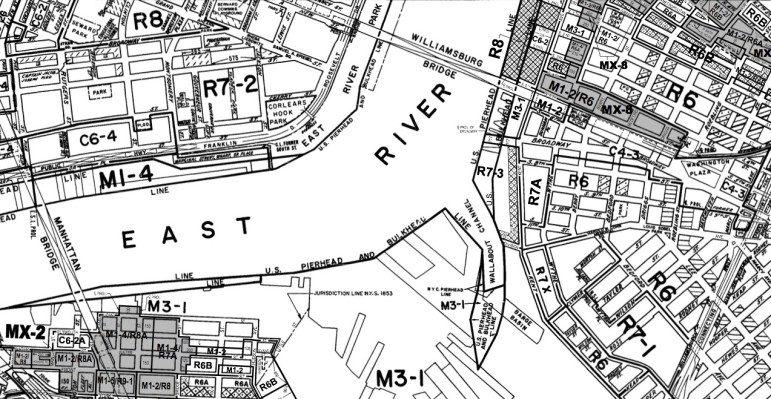

A section of the city’s zoning map. De Blasio’s Department of City Planning has said it’s focused on more than zoning. But doing truly holistic planning takes time, resources and political commitment.

This story first appeared on City & State, with which City Limits is partnering to cover crucial housing policy stories in 2015.

A report published in 2009 and reprinted in 2011 by the New York Department of State makes some interesting observations about zoning and its role in urban planning. For one, “zoning should be adopted in accordance with a comprehensive plan,” which should form its “back bone.” Zoning, the report made clear, should be driven by a concern for “public health, safety, morals or general welfare.”

Under Mayor Bloomberg, there was clearly a disconnect between zoning and planning. The mayor rezoned much of the city, when zoning was rarely part of anything comprehensive, and often involved scant community input.

Mayor de Blasio promises to follow up on campaign promises and bring planning closer to the community. The new chair of the powerful City Planning Commission, Carl Weisbrod, chosen back in February 2014, pledges “ground up” and “comprehensive” planning.

With that in mind, Weisbrod’s DCP has hired more staff, leafleted neighborhoods about contemplated rezonings and held “visioning sessions” at town-hall events where community members are asked for their input.

The former head of Trinity Church’s real-estate arm pledges deep dialogue with local communities, including low-income neighborhoods. That’s what DCP says it is doing in a 73-block area along Jerome Avenue in the Bronx.

But urban planners who spoke with City Limits aren’t exactly convinced. And a number of voices in the south Bronx community and in other neighborhoods such as East New York are also skeptical. That’s partly because the conversations in these areas begin with the de Blasio team earmarking them for development, leading some to feel the die’s been cast. But City Planning also labors under a thick blanket of distrust because of what occurred on Bloomberg’s watch.

Planners we spoke with noted these five ways community planning might be a tough thing for New York City to actually deliver.

1. Comprehensive community planning takes a lot of time

True planning, says Tom Angotti, a professor of urban affairs and planning at Hunter College, is a long and tedious task that can take years. Portland, Ore., recently completed a comprehensive, inclusive planning process; it took three years. So a truly comprehensive planning effort could be a difficult fit with the mayor’s 10-year timeline to build 80,000 units of affordable housing. Ronald Shiffman, a veteran urban planner and a professor of planning at the Pratt Institute’s Graduate Center, feels the mayor should not have imposed a specific timeline to achieve his achieve his affordable housing goals.

2. Comprehensive community planning takes resources

In 1986, around the time the city was ramping up to fulfill Mayor Koch’s 10-year housing plan, the Department of City Planning had a staff of 397. Today, in a city that is a million people larger, it has a headcount of 265.

The lack of funding affects not just City Planning but also the community boards that are supposed to represent neighborhood interests in the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Process, or ULURP. The city charter says City Planning is supposed to “provide community boards with such staff assistance and other professional and technical assistance as may be necessary to permit such boards to perform their planning duties and responsibilities” but that’s rarely the case.

3. Comprehensive community planning takes more than zoning.

Weisbrod’s office tweeted that “Rezoning is a tool, not a goal, for quality, ground-up neighborhood development.” DCP argues that it is now treating rezoning as a means, not an end, to improving neighborhoods.

But Shiffman is skeptical that City Planning has moved on from the single-minded focus on rezoning that characterized its performance over decades and which, he says, “grows out the Department’s unchecked responsiveness to private sector initiated development and their avoidance of community-based planning.”

At an October summit at the Municipal Art Society titled “Building a City for All New Yorkers,” Weisbrod tried to allay community fears, promising a planning approach that involves more than just more community input and increased density. One key feature of the new regime is closer coordination between Planning’s work and the city’s capital budget—which in theory means that the necessary schools, roads, parks and other infrastructure will be in place when neighborhoods begin to get more dense under the mayor’s housing agenda.

“For the city, this is a significant departure from decades of what have been, essentially, bilateral negotiations between OMB and the city’s capital agencies, with limited coordination among them as to where investments are being made,” Weisbrod told the MAS crowd.

That’s “all very good,” according to Angotti, who notes that “DCP once played a central role in the budget process and this was taken away during the fiscal crisis” of the 1970s. “But,” Angotti warns, “this doesn’t necessarily translate to greater access by communities. What’s really needed is to unpack the inordinate power wielded by the bean-counters in the OMB — a power which the mayors bow to.”

4. Comprehensive community planning begins in the community

Eve Baron, an expert in community development, advise taking a wait-and-see approach to the new administration. But she notes that a salient feature of a true community-based plan is that it’s “first and foremost one that originates in the community, not government meeting the community but the community reaching out,” she says. “The community knows its proprieties,” she adds.

The de Blasio administration’s designation of target neighborhoods for development mean the impetus for the discussions around Jerome Avenue, in East New York, in Flushing and elsewhere came from City Hall, not the neighborhoods themselves.

Everything you need to know about comprehensive planning in New York (but were afraid to ask): City Limits magazine, January 2011: City Without a Plan

City planners, Shiffman said, “need to step back and engage community boards and the rich number of community development organizations,” he said. “I don’t believe that’s going on anywhere yet.”

A truly community-based plan, he says, looks at issues crucial to community preservation, such maintaining local housing stock and engaging all members of the community in face to face dialogue.

In its Jerome Avenue study, DCP has said it “intends for the neighborhood study to reflect the community’s vision for the neighborhood, and the agency will strive for local ownership of the study’s goals and vision in partnership with city agencies.”

City Councilmember for the area in Jerome Avenue, Vanessa Gibson, told City Limits she will ask that the City Council to reject the rezoning if that is the community’s wishes.

But Angotti believes communities will be placed in a position where they can’t really say no: “They say ‘Well, look development is going to happen anyway. If we revised the rezoning, you will be able to have some say in how it occurs, where it occurs and by the way, you will be able to get affordable housing through inclusionary zoning.”

5. Community planning hasn’t delivered in New York City in the past.

Angotti said that the city has a “tradition of community-based planning” and even has a legal mechanism to permit it: the 197-a plan.

The 197-a tool was created by a revision of the City Charter to give communities greater input in the planning process. Over a dozen 197-a plans have been adopted since 1992, the last one in 2009, to develop the Sunset Park waterfront.

But the mechanism has its flaws. For one thing, final approval for whatever draft emerges rests with the City Council, where Shiffman says real-estate developers may wield power.

What’s more, Angotti adds, “Not many people do them anymore because the City Planning Commission doesn’t really recognize them and dismisses them as advisory.”

The 2002 Greenpoint 197-a plan was hailed as a success by City Planning, but was “drastically modified as part of the mayor’s plan to rezone areas,” in 2005 says Shiffman.

City Planning is aware of the tremendous distrust it faces, and has taken steps to address it. When residents near Jerome Avenue raised an eyebrow at Planning’s decision to dub the area “Cromwell-Jerome,” a designation that locals had never heard of, Planning scrapped the name. The department has held a Spanish-language info session in East New York—a modest step, but a novel one—and hosted walking tours in the Jerome Avenue area. Planning says it is working with community boards to make their Annual Statement of Needs documents more effective. The planning process, says one Planning official, will be “something that gets designed to meet the needs of each community.” He adds: “We’re not beginning the project with a preconceived sense of the outcome.”

City Planning’s challenge is, amid all the distrust left over from Bloomberg, to somehow balance community desires with the citywide desire for more housing. “We really do have to both of those. We are responsible for the well-being of the city and the city has a housing need. Everybody has to do their part,” the Planning officials adds.

Given those stakes, when Planning and a community sit down and talk frankly, “It’s not like ‘Kumbaya,'” the official says. “It’s really a meaningful exchange.”

From our partners at

“Changes in the city’s zoning laws proposed last month by Mayor Bill de Blasio will affect the entire city and Councilman Kallos believes the community boards may not necessarily have the expertise required to deal with them.”

City Limits coverage of the Bronx is supported by the New York Community Trust.

2 thoughts on “5 Challenges to De Blasio’s Promise of Inclusive Planning”

In 2005 most of the east and south shores of Staten Island were

downzoned to halt over-building. This was done at the request of the

communities involved. Our councilmembers were on board from day-1. They

work for us, and should be held accountable. Don’t like proposed zoning

changes, then make sure your councilmember hears that – loud and clear.

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/10/nyregion/10density.html?pagewanted=all

http://www.silive.com/news/index.ssf/2013/12/parks_to_property_taxes_bloomb.html

Carl Weisbord: in bed with big real estate because he is big real estate.