NYPD

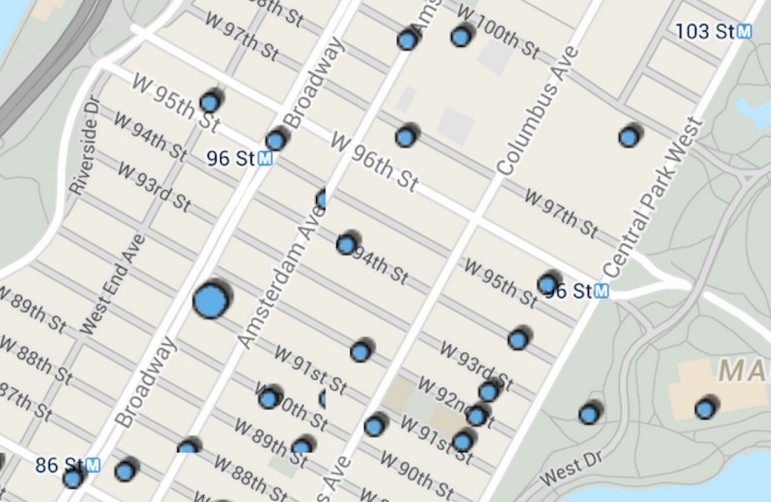

A screenshot of the NYPD Crime Map shows recent offense reports on the Upper West Side.

Shirley’s usual pre-work routine was interrupted when an uninvited man joined her in the shower. This intrusion took place last month not at the Bates Motel, but an even seedier establishment on West 95th Street in Manhattan once known as The Pennington, but now home to “Freedom House,” a 200-person homeless shelter imposed slap dash on a legacy rent stabilized SRO (single room occupancy) population.

Jesse Coburn’s piece, “After the Shouting” covers a great deal of territory, but unfortunately relies too heavily on broad brushstroke studies that have little relation to what is happening on the street or in the shelters themselves. Poorly run facilities not only scar residential neighborhoods, they leave a sad legacy of not helping the people on the inside—the homeless and legacy SRO tenants like Shirley who are held captive by the city’s scattered site and scattered brain policies. If only Mr. Coburn had dug deeper, he’d have found that the story of the human capital squandered in shelters is worthy of an Upton Sinclair expose.

On August 6, 2012, the Bloomberg Administration, with little fanfare and even less warning to the public opened “Freedom House,” moving 400 homeless clients into two rundown SRO hotels, The Pennington and The Continental on West 95th Street. A few weeks later, Ed, a tall, broad shouldered man pulled me over at a demonstration. “You people have no idea, with your charts and figures how much the tenants are suffering, how much our lives have been changed by the shelter tenants. I have been to several doctors and they can’t tell me what is causing my skin condition. I have to share a shower with them. I can’t sleep no more. This ain’t right.” His description sounded like scabies. He said he’d never had any other health issues in his ten years of SRO living.

Another SRO tenant in the building found his path to his room blocked, “by a man twice my age and twice my size,” who threatened to kill him.

Shirley described other situations she and other tenants encountered daily: “I try to sleep through the drug deals in the hallway, and fear that I might emerge from my room at the wrong moment, when a deal is going down.” For SRO tenants who must share common bathrooms in a common corridor with a homeless population of greatly varying needs and classifications, answering the call of nature is sometimes a danger to negotiate, since the opening of Freedom House in their building.

While it is good that Coburn drew attention to problems with the city’s failure to comply with its own charter, which requires it to notify communities and give them input in the siting of shelters and similar facilities, the article falls into a trap. Coburn quotes studies and statements by city agencies as if they are the holy Gospel. Our experience has been that it would be easier to trust the word of Vladimir Putin. Allow us to count the ways this blind faith distorts reality:

1) The article claims there are four shelters on the Upper West Side, when in reality there are 17 facilities in 18 square blocks in the West 90s that house DHS (Department of Homeless Services) clients, including others run by sister city agencies HRA (Human Resources Administration) and HPD (Housing Preservation and Development), as well as a few homeless shelters in major houses of worship.

Having failed to perform a city charter-obligated “Fair Share Survey” prior to siting its latest shelter on the Upper West Side, DHS consistently under-represents the number of local facilities housing residents taken directly from its own homeless pool. Its disregard of the city’s law and reality is so craven, that DHS ignored a property in an HPD program housing 82 homeless clients that abuts the Freedom House property! It is misleading to use the narrow definition of a DHS-run shelter, when similar populations are being housed by other city agencies are housed nearby.

For example, 400 feet east on the same West 95th Street, the Camden, an HRA facility where HRA client murdered an assistant manager, was classified by the 24th Precinct as the “second most dangerous building” on the Upper West Side. Too bad the city didn’t count this in their shelter tally. The murderer was a recent transfer from yet another uncounted city facility, The Yale just two blocks away on West 97th Street. He was moved because he was out of control with a meth addiction. So he was sent packing to another nearby facility where after the killing spree, he was subdued with a baseball bat and a tub of scalding water.

Just two blocks away, the Narragansett, an SRO in an HPD-DHS program, was the scene, a week to the day after the Camden murder of a new transferee murdering a long time HRA client.

Had Coburn spent more on the ground research, he could learn more about the dangers boiling below the City’s statistical Potemkin Village. The fact is a small portion of the Upper West Side has a stunning concentration of facilities that by sheer number and a failure to provide appropriate treatment, tear at the community’s social fabric and first responder resources. This concentration has led to a very significant percentage of murders on the Upper West Side in recent years having occurred in facilities for DHS clients in the West 90s. We would be glad to supply a more complete list.

2) The concerns of Neighborhood in the Nineties are not those of stereotypical NIMBY activists who have no experience with shelters, but instead with the ‘tipping point’ effect on our neighborhood -and with the welfare both of homeless residents and the previous residents whom unscrupulous landlords have sought to push out. Neighborhood in the 90s has consistently criticized badly managed shelters, oversaturation, corruption and waste (Roughly $3,700/month for 8×10′ rooms at Freedom House, which is run by an organization that the comptroller’s office found to have bilked the city out of roughly $1 million, and found sorely lacking in a later audit), and the pushing out of stable low-income clients who then become more vulnerable to homelessness. The New York Times and Capital New York have documented extensively the despicable practices of the owners of the Freedom House buildings and of the shelter operators.

3) While Coburn quotes the Urban Institute follow-up study whose “researchers determined that, on average, crime rates were not higher near supportive housing compared to similar areas with no such development, except for disorderly conduct charges within 500 feet of facilities.” Does the author realize that in densely populated Manhattan, 500 feet encompasses several blocks in different directions, meaning disruption of an entire neighborhood ecosystem comprising thousands of residents, plus schools and stores? N90s has documented a dramatic increase, since the shelter opened, of petty crime, including “smash-n-grab” auto larcenies (many of which are documented with photos on our Facebook page). A chill settled over the neighborhood in late 2014 after the stabbing of a neighborhood building superintendent by a guest of a Freedom House shelter resident; the “knockout game” attack in front of the shelter; the increase in knifepoint robberies; the increase of intrusions into neighborhood buildings and thefts (including in my own building); the increase in drug dealing witnessed by many neighbors; the increase in encampments and sleeping in the park; the increase in public urination and number of strung-out drunks and junkies on the streets; and the rise in aggressive panhandling and harassment of residents and local store employees.

Buildings adjoining the shelter are treated to all night screaming and other noise from shelter residents. Perhaps that’s why the community activists are “shouting.” We need to be heard above the primal screams of shelter residents and through the fog of city and institutional cover-ups. The shelter system is in screaming need of reform, and nothing will be solved if we pretend the problems aren’t grave.

(All names of SRO tenants quoted here have been changed to protect them)

A. Biller

Editor’s response: Jesse Coburn’s article doesn’t paint in the broad-brush fashion Aaron Biller suggests. Jesse spoke to residents in several neighborhoods affected by shelters and supportive housing facilities, including people who live near and/or had protested against facilities; most said that the facilities had had no detrimental effect. Jesse also was very careful to note the limitations in the research he cited, especially the dearth of research on the effect homeless shelters—as distinct from supportive housing facilities—have on a neighborhood.

As Biller acknowledges, Jesse did note that the city has sometimes fallen short on notifying and listening to communities before siting shelters. It is worth remembering, however, that the city charter’s Fair Share provisions only apply to public shelters—not some of the private ones Biller complains about—and do not apply in emergencies, something the city’s homelessness situation certainly could be considered. Jesse didn’t, in fact, report that there are “four shelters” on the Upper West Side as Biller indicates; instead, the article notes that there were four city-run shelters for families and adults at the time of a 2013 comptroller’s report on the topic.

A final note: Biller’s contention that new shelters have led to “a very significant percentage of murders on the Upper West Side in recent years having occurred in facilities for DHS clients in the West 90s” requires context: He cites two murders at separate facilities in 2012, and another at a third facility in 2013, which comprise half the six murders in the precinct over that two-year stretch. -Jarrett Murphy

4 thoughts on “Op-Ed: UWS Straining Under Homeless Shelters”

You ‘progressives’ on the UWS must have the worst councilperson(s) representing you. My councilman would have a lot of explaining if our neighborhood was treated this way.

Helen Rosental is failing miserably on his issue.

Then it’s up to voters in your neighborhood to confront her on this serious issue. We can’t let our elected officials be unaccountable. Either that or ‘fire’ her in 2017.

Thanks for writing this Aaron. You have accurately described what’s going on in the 90’s and the detrimental impact the shelters are having on all our lives who live here. Mr. Coburn has no idea what’s going on in this neighborhood.