Talks about a settlement of a lawsuit over NYPD spying on Muslims have included discussion about whether to pull a controversial report on Muslim radicalization off the department’s website, according to the New York Post.

“The groundbreaking, 92-page report, titled ‘Radicalization in the West: The Homegrown Threat,’ angers critics who say it promotes “religious profiling” and discrimination against Muslims. But law-enforcement sources say removing the report now would come at the worst time — after mounting terror attacks by Islamic extremists in Paris, Boston, Sydney and Ottawa,” the Post reports

In 2008, City Limits magazine published a detailed examination of the state of civil liberties in New York City seven years after September 11. One chapter focused on the report—which, according to Time magazine, was “the most sophisticated government analysis of the homegrown terrorism threat to be made public in the United States.” Here’s an excerpt:

Written by NYPD intelligence analysts Mitchell D. Silber and Arvin Bhatt, it examined five foreign terrorist plots—including the London attacks, the 2004 Madrid train bombings and the murder of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh—and concluded that the plots fit a pattern in which radical Islam drove the participants to their deeds.

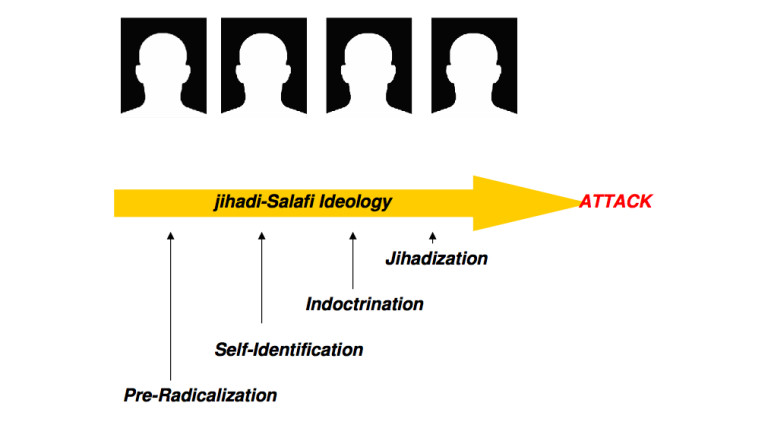

Silber and Bhatt posited a four-stage radicalization process. “Pre-radicalization” is the period before exposure to jihadi- Salafi Islam, a radical interpretation of the Muslim faith. “Self-identification” is what happens when a “cognitive opening or crisis” leads a person to explore radical Islam. “Indoctrination” occurs when the person “wholly adopts jihadi- Salafist ideology” and decides that “action” is required, usually with the help of a “spiritual sanctioner.” Finally, “jihadization” happens when the person decides to become a “holy warrior.”

The report says “there’s no useful profile to assist law enforcement” but also claims that the four-step pattern “provides a tool for predictability.” Not everyone who starts the radicalization process finishes it, of course, but that “does not mean that if one doesn’t become a terrorist, he or she is no longer a threat,” it reads. “Individuals who have become radicalized … may serve as mentors and agents of influence to those who might become the terrorists of tomorrow.”

That means anyone who starts the process is a threat. And that’s where the report really breaks new ground. “Taken in isolation, individual behaviors can be seen as innocuous,” but when seen as part of a process of radicalization, they look more menacing, the report reads. Hence “the need to identify those entering this process at the earliest possible stage.”

The report then applies this framework to six U.S.-based plots (including the 9-11 attacks, which were partly planned in Hamburg) to see how well it matches, and finds at least partial corroboration.

To help with that identification, the report identifies clues that a person has started down the path to radicalization. It names mosques, cafes, cabdriver hangouts, student associations, hookah bars and bookstores as potential “radicalization incubators” and lists “signatures” that someone has adopted Salafism, including “giving up cigarettes, drinking, gambling,” along with “wearing traditional Islamic clothing, growing a beard” and “becoming involved in social activism and community issues.”

Later, the report contends that a hallmark of the indoctrination stage is that “rather than seeking and striving for the more mainstream goals of getting a good job, earning money, and raising a family, the indoctrinated radical’s goals are non-personal and focused on achieving ‘the greater good.'” It also posits that the spread of radicalization in Europe has been exacerbated by the continent’s “generous welfare systems” and “immigration laws that don’t encourage … assimilation.”

New York, it seems, doesn’t suffer from those policy shortcomings, but Silber and Bhatt nonetheless contend that “radicalization continues permeating New York City, especially its Muslim communities.”

Critics of the NYPD’s approach take issue with much of the radicalization report—not just what it says, but what it leaves out. The study only looks at cases of terrorism that involve Muslims; Oklahoma City’s Timothy McVeigh, Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski and Eric Rudolph (who bombed the 1996 Olympics, a health clinic and a nightclub in Atlanta) are recent homegrown terrorists who don’t make the cut, and neither do other terrorists from domestic groups like the Animal Liberation Front or Earth Liberation Front.

What’s more, the report “doesn’t follow the rules of inference, because it doesn’t look to see if the features it sees as connected to violence are present in a broader spectrum of cases in such a way as to make the correlation they are suggesting suspect,” says Aziz Huq, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU. For instance, a concern for the “greater good,” which nonterrorists from Dorothy Day to Jerry Lewis have exhibited, might not be a useful predictor of potential violence.

The report certainly was ahead of its time in identifying “homegrown” terrorists as the predominant threat of the day. While there were homegrown plots to study in 2007, the last several years have seen a multitude of such plots, from the 2009 Fort Hood shooting, the 2010 Times Square car-bomb attempt and the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing to last year’s hatchet attack on NYPD officers and the Charlie Hedbo massacre this month. Of course, it’s not clear that the perpetrators in these attacks tracked the radicalization process as laid out in the NYPD report: The brothers who slew 12 at Charlie Hedbo, for instance, apparently eschewed beards or traditional dress. And one wonders if we can overlook creeps like Anders Breivik, the right-wing gunman behind the massacre in Norway in 2011 who was motivated in part by Islamophobia.

The bigger issue is this: Developing a matrix for identifying radicalization in process is one thing when it occurs in an academic context. It’s more complicated when applied to intelligence work, where it can be used to justify intrusion and surveillance on people who haven’t done anything wrong, including many who will likely never do anything wrong. It gets even trickier when the intelligence apparatus in question is connected to a law-enforcement agency, as is the case in the NYPD.

While Silber and Bhatt stress that “there’s no useful profile to assist law enforcement,” the fact is law enforcement is not simply going to wait and watch when it encounters someone it thinks is on the path to violent radicalization. And when you have cases like the 2004 Herald Square bombing plot—in which an NYPD-paid confidential informant clearly played a role in cultivating the plot for which two men were ultimately convicted and sent to prison—a statistically justifiable suspicion can become a frightening thing to a community that has been surveilled and infiltrated for more than a decade.