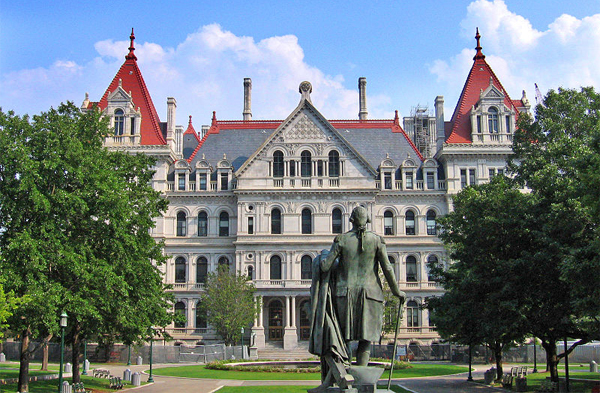

Photo by: iessi

The type of public campaign finance model that Governor Cuomo reportedly supports—a New York City-style, 6-to-1 match of small qualified contributions–will do little to curb the influence of special interest funders in dominating the state Capitol.

The Clean Money Clean Election system of public financing–which provides equal public funding grants for candidates who qualify with a reasonable number of nominal private donations–is much stronger in reducing the role of special interests in buying politicians.

Though the city’s public campaign finance matching model has the support of many advocates, the reality is that after more than four decades of similar reforms being enacted following the Watergate scandal, the role of special interest money is stronger than ever. While the latest round of reforms are invariably hailed by the media and “good government groups” as a major breakthrough, before the ink is even dry the special interests and campaign operatives are figuring out new ways to exploit loopholes. When Congress limits the size of individual donations, the solution for influence peddlers is bundlers, where one donor gets other in the same industry to pony up together to maximize their influence. Or the candidates tells funders how to donate to party committees once they reach the limit for individual candidates. The money continues to flow in ever larger amounts.

Several recent “reform deals” in New York State lowering campaign contribution limits still leave the state’s maximum donation way above federal limits; in reality, for most candidates, the limits are fund raising goals rather than restrictions. In New York, the big rollers are permitted contribute up to $102,300 to each of each party’s state and county committees, who turn around and spend it on their candidates.

While Cuomo failed to advance campaign finance reform over the last year, he has effectively silenced most campaign finance reform advocates from publicly pushing him since they are now his “partners.” With most advocates silenced, Cuomo has done a masterful job of exploiting loopholes in existing campaign finance laws to help his supporters give him massive amounts of donations in violation of the strict letter of the law. According to a report from NYPIRG, since 2010, 142 people or organizations gave Cuomo $8.4 million in donations of $40,000 or more, One real estate developer gave the governor $500,000, through the shell game known as limited-liability corporations; this allowed him to evade the nominal (and scandalously high) limit of $60,800 per donor per statewide race.

We saw a similar pattern a decade ago when Carl McCall (D/WFP) in his race for governor was trumpeted by the same groups as the champion for campaign finance reform while he was drawing national scrutiny for his alleged abuse of pay-to-play (raking in contributions from companies getting contracts from him as State Comptroller).

Supporters of the city’s 6-to-1 matching model point out that the system has increased the diversity of those contributing to candidates, and that smaller, less wealthy donors, can play a greater role, especially in the smaller races for City Council.

In the present mayoral race, the leading fundraiser is City Council Speaker Quinn. The New York Times reports that only about 10 percent of the $6 million she has raised so far qualifies for matching funds, so big money still is playing a big role. One hundred forty nine bundlers, many from the real estate industry, have donated $2.5 million, including a recent spurt of donations from Coke which is worried about the city’s restrictions on soda sales. (Only contributions up to $175 are eligible to be matched 6-to-1 if they come from individual New York City residents.)

The best system of campaign finance reform remains a Clean Money Clean Election system such as Arizona and Maine, where candidates qualify for funding based on raising a certain number of nominal contributions (e.g., $5). The Supreme Court did unfortunately strike down one provision of the Arizona law, which gave the publicly financed candidate more money if their opponent decided to self-finance (e.g., Mike Bloomberg), saying once again that rich people have a first amendment right to buy elections. Still, a Clean Money system can mitigate this decision by providing public funding sufficient to enable candidates to get their message out to the voters in their district.

If New York does decide to enact a NYC-style of campaign financing reform, advocates need to at least demand a much lower threshold for allowing candidates to quality, no discrimination against third party and independent candidates, and much lower limits on campaign contributions and spending limits

The Silver/ Sampson proposed Fair Elections Act in NY that the advocates of the matching funds system are pushing has major problems

1. High qualifying thresholds that make it an incumbent re-election fund. It’s more than twice as hard to get funding for state assembly and senate races than a NYC council races: For City Council districts with populations of 157,025, it takes $5,000 to qualify for public funds. Under the Silver/Sampson bill, assembly candidates (with districts of 129,089 people) would need to raise $10,000 to qualify, while Senate hopefuls (their districts comprise populations of 307,356) face a threshold of $20,000.

2. It still puts private donors in the drivers seat. Candidates who raise more from donors will probably have more to spend, even after matching funds are added in.

3. Publicly funded candidates can receive backdoor private financing from donations from the rich and corporations channeled through party committees. Just last fall, Bloomberg donated $1 million to the state GOP’s “housekeeping” committee.

In contrast, the public funding bill introduced in Congress Fair Elections Now Act (HR 269), is a clean money bill.

As former Supreme Court Justice Brandeis noted, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” Indeed, the elephant in the room of this latest campaign finance debate is the U.S. Supreme Court and their devotion to the concept that the rich and powerful should have the right to buy our government as a exercise in their first speech rights–regardless of whether this means that the rights of the 1 percent trumps the rights of the other 99 percent. Since Watergate, the Supreme Court has repeatedly struck down efforts by Congress and state governments to curb the role of campaign contributions. And with its Citizens United ruling that corporations are people with First Amendment rights to buy elections, the Supreme Court opened up the floodgate to allow special interest to flood into the political system.

Overturning Citizens United is not enough. It would merely takes us back to 2009, when the corporate rich still bought elections. We need a constitutional amendment that really does establish that money is not speech, and that only human beings, not corporations, are entitled to constitutionally protected rights. Amending the U.S. Constitution is a very difficult task. But realistically anything short of such an amendment will be unsuccessful in establishing democracy in our electoral system.

Beyond campaign finance, a more fundamental reform would be for New York – and the U.S. – to finally join the overwhelming majority of the world’s other democracies in moving to a proportional representation system of elections rather than our antiquated and undemocratic winner-take-all system. Proportional representation (parties get seats based on their percentage of votes) creates legislative bodies that much more accurately reflect the political perspectives of the voters than the U.S. system of giving voters the choice between two parties both dominated by special-interest money.

Winner-take-all over-represents majorities and under-represents minorities to make most political districts one-party states. For example, the 6-to-1 advantage of Democratic enrollment over Republican enrollment in NYC gets magnified into a 12-to-1 advantage of 47 Democratic councilmembers to four Republican councilmembers, despite the presence of public matching funds and term limits. With proportional representation, there would no doubt be many third party councilmembers as there were when New York City had it between 1938 and 1945.