Photo by: Alex Morfin

In 1980, a promotion policy was put forward by Mayor Ed Koch, who wanted to be known as the education mayor and judged by student test performance. He championed a promotion/retention effort built around results obtained on the citywide test. He talked about returning to tough standards. He received favorable press for this bold initiative.

Decisions on promoting children would be based on their performance on the city’s annual reading and math tests. Score a year or more behind and you’d be retained in fourth and seventh grade, the so-called Promotional Gates.

Koch’s chosen chancellor held obligatory hearings, where mothers and fathers raised rational arguments against the policy: unreliable data; not enough highly-skilled teachers to reach kids in a way the schools had been unable to before; the harmful, disruptive impact keeping kids back would have (the specter of “bearded 7th graders”); the lack of an appeal process; and the likelihood of insufficient funding to support the program.

The school system didn’t listen to parents. But it did listen to its bean counters. An arbitrary cutoff score was initially set for each Gates grade to separate students who met the promotion criteria from others who would be eligible for retention. Based on preliminary data, the budget office projected how very high the cost would be for the instructional services needed by so many low scorers, including money for prescribed summer school. No problem, the administration effectively said. The cut-off points for holding kids back were immediately lowered—literally, a new bottom line—and a more affordable plan adopted. So much for standards.

The chancellor then asked the city’s 32 school districts to tell him what practices worked best in reaching the holdbacks. Clearly, this was a policy in search of a program. The mayor and chancellor, having rejected input from the public and not thought out the consequences, lurched ahead.

Three or four years later, five independent studies came out concluding the program had come up short largely because of the very problems parents had warned about. The Board of Education stuck by its own statistics and hailed the program’s success, distorting test data to show an exaggerated rate of promotion after summer school. However, by 1984, the city had quietly begun phasing out the program. In short, Gates (no relation to Bill) was a failure.

The episode should have served as an historical object lesson for the current administration. Instead, Mayor Bloomberg has recited the “let’s end social promotion” mantra in every grade. He took credit when the number of holdbacks almost vanished in 2009. Their near-disappearance was because the cut-off scores needed to reach “Level 2,” the threshold of promotion, had been set so low that kids could advance to the next grade by guessing. The mayor was too busy to acknowledge this fact as he ran for re-election to a third term.

In 2009, Albany was finally forced to admit its exams lacked rigor and that tough standards had to be imposed. So, the state and its test publisher increased the number of items required to pass in 2010. Many more students wound up in Level 1, the lowest performance category, making them eligible for additional services. Upon that news, the Board of Regents approved a waiver: Districts wouldn’t have to provide such costly help. As had happened under the Koch administration, which scaled back its own standards in the face of fiscal constraints, city students who needed extra support did not receive the services to the extent they should have. Once again, budget trumped need.

But the Bloomberg administration has done more than echo the Koch administration’s mistakes on the use of standardized tests to govern promotion. It has expanded on them. High-stakes test data have become the basis for denying tenure to teachers and rating their effectiveness via complicated value-added formulas that give major weight to how well their students do on statewide exams whose scoring in recent years has been anything but reliable. And flimsy test results have been overextended to generate school report cards, identifying and justifying which will be closed, restructured, turned around, etc.

All but invisible amid these furies, the troubled promotion program has been relegated to secondary or tertiary status, an ironic outcome, perhaps—one showing how education has devolved from focusing on the children to a preoccupation with administrative and organizational matters.

But the voices of parents that were long ago ignored never died. Unaddressed concerns have grown louder about how testing and its misapplied results have damaged education. A spectrum of resistance is emerging now among parents who question and conscientiously object to putting their sons and daughters through the testing wringer. The proposals range from advocating that informed parental consent be a pre-condition for testing, to more boldly opting out of a program some see as inimical to learning, to flat-out calling for a boycott of next months’ test.

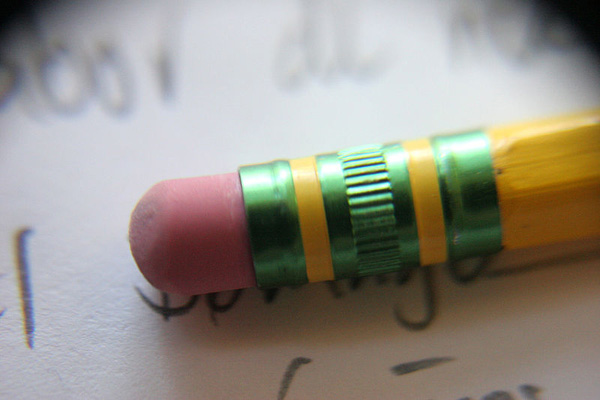

We shouldn’t forget that our current raging debates started in the classroom. Somehow I feel a mixture of ambivalence and perverse consolation in knowing that children hold in their hands the most potent weapon in education today: the No.2 pencil. Armed with this, they fill in circles on answer sheets that control the fate of teachers and schools, as well as their own.