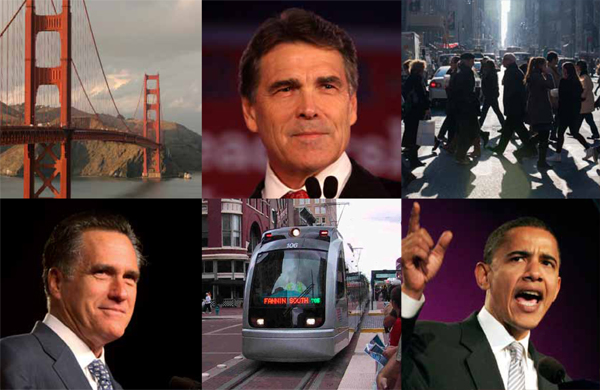

Photo by: Steven Pavlov, Gage Skidmore, WhisperToMe and Marc Fader

Urban policy has—not surprisingly—not been a hot topic at presidential debates this year. But like every president since FDR, the next occupant of the White House will have an impact on America’s cities.

Shortly after lunchtime on the day of the 2004 New Hampshire primary, Joe Lieberman’s bus pulled up to an elementary school on the east side of Manchester. Waiting there for him were three men who clearly had been sleeping on the street before they, briefly, became part of the Connecticut senator’s campaign. On a cue from a campaign staffer, as Lieberman descended from his coach with the assembled media watching, the three men began waving signs and energetically shouting, “Go Joe! Go Joe! … Joe-mentum! Joe-mentum!” Lieberman greeted a few voters, told reporters a somewhat sad anecdote about his lucky tie and got back on the bus to more cheers from his three biggest fans. When the votes were tallied that evening, Joe-mentum placed fifth.

This month New Hampshire will again occupy center stage in an American presidential race, and Manchester will be the backdrop of some of the wall-to-wall coverage. But except for those who get a few bucks and a free lunch in return for playing campaign scenery, the city’s significant homeless population will be invisible in that narrative. So will the other issues facing the largest city in the Granite State, like a poverty rate 37 percent higher than the state average, a wave of layoffs this summer at a local hospital and a brewing debate over its designation as a “sanctuary city” for immigrants—none of it the stuff of gauzy campaign commercials.

“New Hampshire—even though it’s more of a historically industrial state—it has a sort of pastoral image. Where they’re campaigning or doing publicity in New Hampshire, it’s in a barn or in a little town hall … whereas Manchester or Portsmouth or smaller cities are more representative of the state,” says Michael Bellefeuille, a Manchester native who runs a blog for an organization called Livable MHT (the acronym is a reference to the city’s airport). “The image that they’re portraying, it doesn’t necessarily address the city.”

But this is no surprise. U.S. presidential campaigns are built around appeals to the American heartland, a mythical place of farm families and simple wood-framed houses amid acres of wheat and corn. “They taught me values straight from the Kansas heartland, where they grew up: accountability and self-reliance,” a certain Illinois senator said in a 2008 campaign commercial, “love of country, working hard without making excuses, treating your neighbor as you’d like to be treated.” Sarah Palin got heat for referring to the “real America” but Barack Obama got a free pass for suggesting that loyalty and work ethic are somehow unique to the rural U.S.

Some of his predecessors were far more explicit. “The mobs of great cities add just so much to support of pure government as sores do to the strength of the human body,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1781’s Notes on the State of Virginia, and in a 1787 letter to James Madison, he added, “I think our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries as long as they are chiefly agricultural; and this will be as long as there shall be vacant lands in any part of America. When they get plied upon one another in large cities, as in Europe, they will become corrupt as in Europe.”

These weren’t just idle words, noted planner Leonardo Vazquez in a 2006 Planetizen commentary: “Jefferson was able to hardwire an anti-urban bias into the culture of the United States” in denying any powers to cities and towns in the U.S. Constitution and organizing land purchases in a way that discouraged dense population. And these disparities only deepened over time. “I do think that overall, over the years, there is a consistent sort of anti-urban animus in Washington,” says Roger Biles, a history professor at Illinois State University. “And historically a lot of that simply owed to the fact that a lot of the people who were elected to Congress and went there came from gerrymandered states where they were disproportionately representing the interests of rural people. Even as the nation became more and more urban, that wasn’t reflected in the composition of Congress.”

Today, some 87 million Americans—more than the population of Germany, France or the U.K.—live in cities with populations of 100,000 or more. Nearly a third of the U.S. population dwells in central cities; only a fifth lives in a rural setting. America’s cities have built-in advantages for addressing some of the country’s deepest problems, offering energy-efficient living, mechanisms for integrating immigrants, economies of scale for health programs and more. At the same time, metropolitan America faces tremendous problems: a $35 billion to $64 billion tab over the next 20 years just to preserve the current mass transit system, massive municipal pension obligations and in some cases stunning population losses, persistent foreclosure crises and dangerously high unemployment. The potential in America’s cities, and the risks they face, matter beyond their borders. “Nations do well when their cities do well,” says Hank Savitch, an urban-policy expert at the University of Louisville. “Cities are capital-intensive, labor-intensive territories that promote and catapult nations economically.”

But don’t expect America’s cities—their problems or their potential—to be on the radar this campaign season. The 2012 race, like almost every prior one, will be about something else.

In 1988, The New York Times’ Sam Roberts wrote about the neglect of urban issues during the Michael Dukakis–George H.W. Bush presidential race, offering that their treatment was best described by an editorial cartoon he’d seen. “Sir, do you have an urban agenda?” the cartoon had a reporter asking a candidate. “Four panels of the cartoon follow, in which the candidate remains mute,” Roberts wrote. “Finally, the reporter asks, ‘Can you be more specific?’ ” Two decades later, the Times editorial board detected a similar failing in the early stages of the ’08 race. “The cities have been the hardest hit as federal policies have failed or gone missing in education, housing, health care, jobs, transportation and environment, to name a few,” the Times opined, “yet urban issues have gotten scant attention in this campaign.”

This near silence reflects two political realities. The first is that Democrats, not Republicans, win cities: Obama bested Republican nominee John McCain by 2-to-1 margins in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Philadelphia and New York (all loyal “blue” states) but also in St. Louis, New Orleans and Jackson, Miss.—cities he dominated in states he lost. Neither party has much incentive to go after urban voters; Democrats can usually count on them, and Republicans can basically count them out.

The second reality is that since World War II, America’s population has—thanks to federal policies like highway construction and mortgage interest tax deductions—shifted to the suburbs. That’s where the swing voters (be they Reagan Democrats or soccer moms) are, so that’s where candidates aim their arguments. This has only reinforced a cultural distaste for cities. “We’ve got an agrarian culture, and the notion of moving up in America is moving to some rural locale rather than to an urban core,” says Savitch.

This isn’t to say that cities never get addressed. Urban issues arose at all three Ford-Carter debates in 1976, at a time when New York City’s fiscal crisis was in the headlines and urban unrest was not a distant memory. Four years later, cities were mentioned a remarkable 38 times in the two debates among President Carter, Ronald Reagan and third-party candidate John Anderson.

In the wake of the Los Angeles riots, the 1992 presidential campaign touched a few times on urban problems. (“I think we’ve been fighting from Day One to do something about the inner cities,” President Bush said at one point.) In ’96, the vice presidential candidates jousted over urban policy, with Bob Dole’s running mate, Jack Kemp, saying of Bill Clinton and Al Gore, “They have abandoned the inner cities. There’s a socialist economy. There’s no private housing. There’s mostly public housing. You’re told where to go to school. You’re told what to buy with food stamps. It is a welfare system that is more like a third-world socialist country than what we would expect from the world’s greatest democratic free enterprise system.”

Campaign rhetoric, of course, bears little connection to the reality of governing. Whether or not they discussed urban policy as they barnstormed for votes, once elected, every president in modern times has had an impact on cities—by acts of omission and commission. And as far-out as Kemp’s critique sounds, it reflects misgivings about federal urban policy that have dogged cities since Harry Truman.

The boilerplate version of modern American urban history is that cities were destroyed by a menu of activist federal policies implemented during the 1960s: public housing that drowned neighborhoods in low-income pathologies, urban-renewal efforts that uprooted city communities to make way for ill-conceived new developments, and Great Society initiatives that wasted a fortune on programs doomed to fail. There are elements of truth in that telling, but as Biles demonstrates in his new, sweeping history of federal urban policy, The Fate of Cities, it leaves most of the story out.

Fact is, America’s cities did not enter the postwar period in pristine shape. Many still bore the scars of the Great Depression, during which Franklin Roosevelt showed little interest in direct aid to cities. FDR’s successor, Truman, secured a major federal commitment to urban redevelopment and fought with some success for low-income urban housing, but met stiff resistance in Congress. Some Republicans were concerned about increased government spending; many had resisted the creation of public housing in the 1930s out of an ideological dislike for government intervention in the housing market. But other Republicans, joined by Southern Democrats, were driven mainly by fears that Truman’s proposals might speed racial integration.

After Truman’s struggles, Dwight Eisenhower largely ignored the needs of cities as his administration pursued the construction of highways that helped empty the urban cores of people and businesses. John Kennedy, Biles notes, came to office with a distinctly urban pedigree and raised great hopes for cities but largely failed to deliver, falling short of the votes needed to create a cabinet-level agency focusing on cities because race-obsessed members of Congress worried the president would nominate a black man to head it.

Urban America had its moment in the spotlight under Lyndon Johnson, who would actually devote major addresses to Congress to the topic of cities, created the Department of Housing and Urban Development and pushed through an ambitious package of legislation for cities. Most of those programs are remembered as disastrous failures, but the critiques can get fuzzy on the details. One dis is that the programs were too top-down, but Johnson’s “community action plan,” which sought to empower urban residents to chart their own renewal programs, is simultaneously faulted for being naively bottom-up. Johnson is pilloried for pushing programs that promised more than they delivered, but that’s partly because the budgets Congress approved never met the programs’ needs. The Model Cities initiative might have registered more success if Johnson had stuck to the original plan of concentrating aid to six major cities; instead, horse trading to get more congressional support, the program expanded to help 66 cities, diluting the available funds.

Richard Nixon came to office against a backdrop of urban unrest for which liberal ideology proved a convenient scapegoat. He began dismantling Great Society programs and stopped building public housing, but he did launch the effective CETA job-training program. Gerald Ford threatened no such innovation and spent his brief time in office resisting urban spending, whether for national programs or to help individual cities facing bankruptcy. Jimmy Carter came to Washington riding a wave of reform sentiment and promised to help cities. He created urban development action grants that used federal funding to leverage private redevelopment investment in cities but, foiled by his own disinterest in activist approaches and his toxic relationship with Congress, never achieved a comprehensive urban policy. A Carter-appointed presidential panel on urban policy notably concluded, “There are no ‘national urban problems,’ just an endless variety of local ones.”

Reagan hobbled HUD and starved mass transit, but- George H.W. Bush projected a “kinder, gentler approach” and appointed the “bleeding-heart conservative” Kemp as housing chief. Innovative programs like one that would let public-housing residents buy their homes won approval, but budget hawks in the administration quickly choked off funding. Even after the Rodney King riots exposed the dire needs of cities, little was done, as the White House shied away from expensive solutions and the Democratic Congress resisted giving the politically weak president a legislative victory on the eve of the ’92 election.

Clinton brought new hope to cities, but the optimism was misplaced. His early move to create tax-free areas called empowerment zones in distressed inner cities was a modest execution of a Republican idea. After the 1994 elections gave conservative Republicans control of Congress, Clinton moved to the defensive and to the political center: His urban agenda evolved to concentrate on reducing crime, retreating from public housing and introducing time limits and work requirements to welfare. Any political capital he earned though re-election in 1996 was absorbed by the intern and impeachment drama of ’98 and ’99. Biles gives Clinton and his housing chief, Henry Cisneros, credit for saving HUD from Republicans intent on killing the agency off, but broader urban achievements alluded the administration.

In the summer of 2002, George W. Bush addressed HUD employees. “Let me first talk about how to make sure America is secure from a group of killers, people who hate—you know what they hate?” the president asked. “They hate the idea that somebody can go buy a home.” Indeed, Bush’s total focus on the war on terrorism shifted domestic issues to his administration’s back burner, and urban policy virtually off the stove. Bush cut public-housing operating support and capital funding. He signed a transportation bill that earmarked $45 billion for mass transit, but it spent four times that on highway construction. “What will I do for public transport?” Bush famously said at a campaign rally. “I will improve the economy so you can find good enough work to be able to afford a car.”

From 1969 through 2008, seven presidents occupied the Oval Office; their rhetoric varied and their ideologies differed, but all seemed to concur in the diagnosis that aggressive action in cities was politically or practically unfeasible.

“Government has been discredited, so we don’t try anymore,” says Biles. “There’s lots and lots to be said about the failures of urban renewal. There’s no question that Johnson’s Model Cities program was a failure from the get-go. But then the question becomes, Does it mean that government has no useful role to play?”

Four years ago, Obama hinted that he had a different take. In June 2008, the putative Democratic nominee spoke to a group of mayors in Miami and pledged a new dedication to metropolitan policy. After pointing to his own experiences as a community organizer in Chicago, the then senator said, “We need to stop seeing our cities as the problem and start seeing them as the solution,” and pledged to appoint “the first White House director of urban policy to help make it a reality.” The president delivered on his promise a month into his term, naming Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrión to lead the new office. “He’s going to be responsible for coordinating all federal urban programs,” Obama said. “Now, rebuilding our economies and renewing our cities is going to require a true partnership between mayors and the White House, and that partnership has to begin right now.”

Some urban champions were less than thrilled with the approach to cities in the administration’s first months. Carrión lacked national stature, and while he undertook an extensive tour of urban areas and oversaw an unprecedented government-wide review of the impact of place-based federal policies, his office had little visibility amid fights over the stimulus bill, the mission in Afghanistan and health care. Advocates grew anxious. “What Happened to the Office of Urban Policy?” asked an article at TheRoot.com. “After 100 days, Obama’s shiny-new dream for our cities is looking more like a bureaucratic nightmare.”

In fact, Obama has launched an interesting menu of initiatives aimed at helping cities. His Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative encompasses the Choice Neighborhoods program—which gives grants to cities to come up with plans for transforming public housing developments into mixed-income, mixed-use communities—and Promise Neighborhoods, which funds local initiatives that take a comprehensive approach to fighting concentrated poverty. The Sustainable Communities Initiative pools money from the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Transportation and HUD to achieve maximum effect in particular places that offer a chance at energy-efficient, economically sound development. In a city where an unremediated brownfield prevents housing from being built next to a train line, the theory goes, the three-agency partnership could fund the environmental cleanup, help launch the housing and establish links to the rail system for the new residents.

The Obama programs clearly reflect lessons the Great Society taught. Existing programs are being concentrated for maximum effect, duplication is avoided, and top-down prescriptions are eschewed in favor of programs that communities design for themselves.

But while Obama has cited famed urban planner Daniel Burnham’s charge to “make no little plans” in selling his urban ideas, the scale of the programs so far doesn’t allow for anything other than small-bore optimism. Congress has never met the president’s funding requests for any of his urban programs. The past two years, the White House has asked for $250 million for Choice Neighborhoods, but Congress has come through with less than half that amount. Last year’s ask of $210 million for Promise Neighborhoods was met with $30 million in funding. The budget for this year’s Sustainable Communities Initiative stands (at press time) at zero.

If the Great Society programs suffered from overambitious promises, they also wilted from insufficient budgets, and that latter threat exists for the Obama initiatives as well. Altogether, the Choice, Promise and sustainability programs have distributed grants to 187 communities, but only to a tune of $230 million to date—about half what the Air Force will spend on ammunition this year. While the plan is to learn lessons from those cities and apply them to future programs, it’s not clear that the will or the money will be there to take them to scale.

Nor is it clear who’ll be overseeing Obama’s urban policy even for the rest of his current term. HUD secretary Shaun Donovan remains in place. But Obama’s domestic-policy chief, Melody Barnes, was scheduled to leave the administration at the end of 2011. Carrión left his post 18 months ago and was never formally replaced. The president’s special adviser on urban affairs, Derek Douglas, took over direction of the Office of Urban Affairs, but he was also planning to leave at year’s end.

At the Republican debates this year, cities have rarely been mentioned, but one could catch whiffs of urban policy. Michele Bachmann blamed the housing crisis on the Community Reinvestment Act, while Herman Cain briefly resurrected the old idea of tax-free “empowerment zones.” Rick Perry blamed poverty on a president “who’s a job killer,” Rick Santorum on “the breakdown of the American family.” Mitt Romney called for reducing anti-poverty spending, while Ron Paul said he wants to eliminate HUD; according to a Des Moines Register poll, a majority of likely Iowa caucusgoers agree with him.

Newt Gingrich has said more than most. At a September debate, Gingrich claimed that “Bad government has destroyed the city of Detroit.” He didn’t say exactly how, but his idea of “good” government includes repealing financial regulations, declawing the FDA and EPA and lowering taxes. He’s blamed unions for trapping poor kids in failing classrooms, then suggested that child labor laws should be relaxed so students can get jobs as librarians or janitors in their schools. Last month the former speaker said, “Really poor children in really poor neighborhoods have no habits of working and have nobody around them who works … They have no habit of ‘I do this and you give me cash,’ unless it’s illegal.”

Divisive rhetoric aside, should Obama lose, urban policy will retreat even further down the list of federal priorities. But even if the president wins, a Republican-controlled Congress is unlikely to permit the White House to expand its urban programs. Concerns about the deficit are only part of the picture. Some conservatives are openly hostile to the idea of comprehensive planning and sustainability policy. Reacting to remarks the president made in 2009 about his efforts to get metro areas to do more thoughtful planning, the Heritage Institute warned: This “heralds a process that could likely lead to an unprecedented federal effort to force Americans into an antiquated lifestyle that was common to the early years of the previous century. More specifically, these initiatives reflect an escalation in what is shaping up as President Obama’s apparent intent to re-energize and lead the Left’s longstanding war against America’s suburbs.”

In the absence of broad federal urban policy, many cities have taken their own steps to secure their futures. New York has adopted progressive environmental policies under Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s PlaNYC. Boston has innovated ways to deal with vacancy and abandonment. Portland, Ore., has undertaken an inclusive long-term-planning project.

But for every example of independent ingenuity, there is an instance of municipal desperation, like Chicago’s selling ad space on its bridges. From high-speed interstate rail to gun control, there are issues for which cities simply cannot make meaningful policy on their own, because the problems lie beyond their borders and their budgets. Other countries realize that cities help generate broader economic growth and deserve investment. In France, says Savitch, the national government covers 70 percent of municipal expenses. “We suffer exactly the opposite,” he notes.

Cities will obviously benefit from broad improvements in America’s economy and fiscal situation. In a November letter to the supercommittee charged with reducing federal spending, the U.S. Conference of Mayors called for general policies like closing corporate loopholes, repatriating profits and redirecting savings from the end of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars to infrastructure. But cities also have special needs: The National League of Cities has a 230-page blueprint for national urban policy that covers everything from Internet access to freight traffic to counterterrorism.

Many of those issues intersect. Christopher Emerson, who runs a homeless-services center in Manchester, says the shortcomings in the city’s transit hinder efforts to help the homeless put their lives in order. No bleeding heart, Emerson says many of the homeless are as much to blame for their problems as society is. But they do have a legitimate gripe, he allows, when they say they can’t get to an appointment because of the transit system’s scarce service.

“We’re watching our numbers rise here, not dramatically but steadily. It’s going to get worse,” he says, adding that his colleagues at shelters “feel the tide coming.” Officially, Manchester claims only 400 homeless people, but that’s a significant number for a city of 110,000. Many of the homeless are not from Manchester but have come because the city is known to have a shelter system. Occasionally someone will complain that homeless facilities like Emerson’s are attracting a problem population to Manchester’s streets.

But Emerson sees nothing strange about people coming to a city for what they need: “They do the same thing for medical care. They come to the big city for the malls. Why would we single out homeless services as being weird or inappropriate? It’s consistent with how urban, suburban and exurban societies function.”