Photo by: City Hall

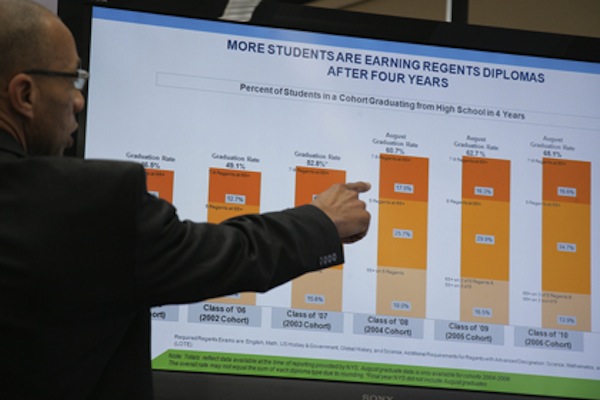

Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott presents this year’s Regents results. High school principals faced new scrutiny on Regents scores in 2011–one of many pressures on the city’s school leaders.

Overshadowed by the threat of teacher layoffs, New York City public school principals faced a suite of challenges as the 2010-11 school year drew to a close: Budget dickering and back-room negotiations meant colossal delays in school budgets and deep uncertainty about faculty layoffs, hiring and teacher evaluations linked to tenure. Funds that prudent principals had saved for the proverbial “rainy day” were tapped by the Department of Education, leaving school coffers bare. Changes this year at the top in DOE’s Tweed Courthouse headquarters meant that some schools were still waiting for chancellor-signed diplomas less than 24 hours before graduation. And concerns that Regents scored might be “scrubbed”—re-scored to push students over the magical 65 passing score—meant that tens of thousands of exams had to be reviewed and then were hand-scanned at schools and faxed to Albany for distant scoring, a process that consumed hours and increased potential errors in coding, transmission and communication—and that roundly contradicted the state’s long-standing policy barring the scanning of Regents exams to protect their integrity.

The wild end of the school year underscores a growing realization that the long-celebrated ideal of principal autonomy—held as a pillar of DOE reforms that put power and responsibility in the hands of school leaders—has eroded in practice, school leaders say, given the demands of evaporating budgets and increasing accountability.

Simply put, being a principal is harder than it has ever been, even as more schools open and a greater proportion of school leaders come from non-traditional training programs like the city’s Leadership Academy and New Leaders for New Schools. City Limits spoke with principals who lead three distinctly different high schools (coincidentally, all are in Brooklyn) to try to understand the challenges, satisfactions and aspirations of those who occupy the leader’s chair, a.k.a., the hotseat.

Autonomy: Decentralizing Power to the Schools

The principle of autonomy, championed by former Deputy Chancellor Eric Nadelstern, promised school leaders the economic and philosophical freedom to run their schools without close scrutiny—provided specific achievement benchmarks were met. The idea was that empowering principals would foster excellence. In a competitive market, strong school leaders and their schools would serve as “best practice” models for others.

Controlling school budgets and hiring were the two signature features of principal autonomy, principals say. But current financial reality made financial autonomy moot—by default, if not by design—when Tweed officials decided to take back money that some school principals had saved from one year to the next. For some schools, those rainy-day savings amounted to hundreds of thousands of dollars.