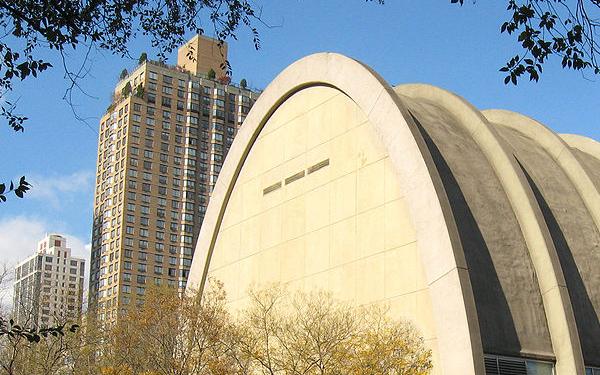

Photo by: Jim Henderson

The waste transfer facility would be accessible by an entrance ramp bisecting the Asphalt Green complex, which some opponents of the facility argue, as a park, is subject to public doctrine. They challenged the city on this issue in court and lost.

To some, Mayor Bloomberg’s Solid Waste Management Plan is a move in the direction of environmental justice that will relieve overburdened neighborhoods of handling the bulk of other New Yorkers’ garbage. Others argue that the plan is set to ruin their neighborhood by bringing the trash there instead.

On Wednesday, June 15, citizens, community activists and politicians gathered on the basketball court of Asphalt Green Park to rally against the Marine Transfer Station (MTS) that the Solid Waste Management Plan (SWMP, pronounced “swamp”) calls for locating on East 91st Street. Participants in the rally held up signs with slogans such as, “Fund classrooms/Not trash!” and “Don’t trash the park.” Many children attended, holding up signs of their own or running around on the Astroturf beside the court.

New York City produces about 25,000 tons of refuse every day. About half of it is generated by businesses, who pay for private companies to collect their waste. The rest of the garbage comes from residences served by the Department of Sanitation (DSNY). Until the closure of Staten Island’s Fresh Kills landfill in 2001, DSNY trucks carried residential trash to marine transfer stations, where it was loaded onto barges and floated to Fresh Kills.

As the city began to shut down Fresh Kills in the late 1990s, more and more residential garbage was diverted from the barge system to private waste transfer stations, where companies collected trash from DSNY trucks and loaded it onto long-haul trucks that carted it out of the city.

Bloomberg’s SWMP, approved in September 2006, lays out the city’s solid waste management plan through 2025, addressing the areas of Waste Prevention and Recycling, Long Term Export, and Commercial Waste. The proposed East 91st Street Marine Transfer Station is part of an effort in SWMP to get the city’s waste off the roads and onto barges again, and to make each borough responsible for its own waste. The SWMP calls for a total of four Converted Marine Transfer Stations, the others being at North Shore in College Point, Queens; Hamilton Avenue in Sunset Park, Brooklyn and Bensonhurst in Southwest Brooklyn.

Is it a park?

East 91st was previously the site of an MTS from 1940 until its closing in 1999. Community members of the Upper East Side, many of whom have resided in the area since before the previous MTS closed and can recall its adverse effects, say that any densely-populated residential area is an inappropriate location for a waste station. In 2009, New York State Senator Liz Krueger posted a press release on the New York Senate website stating that the 91st Street location is the only of the four proposed sites where there is no commercial zone separating the facility from the closest residences.

The facility would be accessible by an entrance ramp bisecting the Asphalt Green complex, which some opponents of the facility argue, as a park, is subject to public doctrine. They challenged the city on this issue in court, claiming the MTS could not intrude on parkland without approval from the New York State Legislature. On June 7, the Appellate Division, First Department, upheld a lower court’s decision that Asphalt Green and Bobby Wagner Walk are not parkland, and therefore not subject to public trust doctrine.

The rally was held on Asphalt Green in part as a reaction to this ruling, with those in attendance arguing that the complex is in fact a park. Jennifer Ratner, community activist and one of the main rally organizers, mentioned to the crowd that in setting up for the event, the Asphalt Green staff had to ask youths playing a basketball pick-up game to leave.

Council Member Jessica Lappin of Manhattan’s 5th district, the first speaker at the rally, argued against furthering pollute the air of an area where public school children learn to swim for free and local residents are able to exercise.

“We have some of the worst air quality in the City of New York, not because I say so, because the Department of Health says so,” Lappin said, referencing the 2008-2009 New York City Community Air Survey that showed the air on the Upper East Side to have some of the highest pollutant concentrations. “So why on earth would we put up to 54 garbage trucks a day on York Avenue?”

Worries about truck traffic

The facility at East 91st Street would receive waste from four of Manhattan’s 12 sanitation districts–those covering Times Square, Gramercy Park, Murray Hill, Stuyvesant Town, Sutton Place, Peter Cooper Village, the Upper East Side, Yorkville, Roosevelt Island and East Harlem. The garbage would be exported through barge and rail transport.

The garbage of the other eight sanitation districts is brought by truck to a waste-to-energy facility in Essex, New Jersey. Vito Turso, Deputy Commissioner for Public Information and Community Affairs at the DSNY, said the amount of waste that can go to Essex is limited by the capacity that Essex can rent to the city and a need to limit truck traffic and on city roads.

The April 2005 Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the East 91st Street facility projects that the peak amount of truck trips per hour will actually be even higher than Lappin had expressed concern about: 56 trips per hour at about 9 am, with an estimate of 5-56 truck trips per hour during the mid morning. For other times of day, the FEIS estimates there to be 0-15 truck trips per hour in the late evening and zero in late afternoon or early evening.

Ratner said she had invited Speaker Quinn to speak at the rally, asking for her comment on the decision of the East 91st Street location. Although Quinn did not attend, her communications department handed out written statements stating that the building of MTSs was done with community input and that every neighborhood is expected to do its part. It also mentioned the recycling station that will be included in Speaker Quinn’s West Side district.

Following the rally, the office of the mayor also released a statement about the East 91st Street MTS.

“The East 91st St. Marine Transfer Station will allow us to deliver on the commitment we made to all New Yorkers to improve our solid waste management plan by making it more environmentally friendly, cost-effective, reliable, and fair to all five boroughs,” Julie Wood, spokesperson for the Mayor, stated via e-mail. “In order to achieve that fairness, each borough must manage its own waste – and that includes Manhattan. No exceptions.”

The e-mail from the mayor’s spokesperson included background information stating that the DSNY vehicles on York Avenue will not be queuing. The Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) from December 2004 states that the new facility is designed specifically to eliminate queuing, on York Avenue or any other City Streets.

The proposed MTS will also contain a “state of the art odor and ventilation system” to filter the air and keep unfiltered air from escaping the facility when the doors open, according to the DEIS. The facility doors will automatically close after collection trucks enter or exit. The facility will also seal waste into containers instead of loading it onto open barges, the DEIS states. This is different from the previous facility, which used technology that dated back as far as the 1800s, Turso said.

The question of fairness

Environmental justice organizations point out that under the existing remnants of the pre-SWMP system, many neighborhoods with private transfer stations that process the waste of other communities are predominantly low-income and of color.

Elizabeth Yeampierre, Executive Director of United Puerto Rican Organization of Sunset Park (UPROSE), part of the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance (NYC-EJA), notes that waste stations have been in neighborhoods such as the South Bronx, Williamsburg, and Sunset Park for many years, handling their own waste and that of Manhattan.

Yeampierre says the recommendations that NYC-EJA and other environmental groups made to the administration were motivated by trying to come up with a plan that would benefit the entire city and would create relief for overburdened communities with health disparities. People who live in New York have no choice but to deal with infrastructure, she says, and that the Upper East Side needs to accept the responsibility as other communities have.

“Every single community produces garbage. Every single community uses energy. Every single community benefits from all of this infrastructure and every single community should be accepting their fair share of the good stuff and the bad stuff,” she says.

NYC-EJA, along with NY Lawyers for the Public Interest and Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods (OWN) worked with the Bloomberg Administration and City Council since 2001 in developing the 2006 SWMP, according to the NYC-EJA website.

Councilman Dan Garodnick of the city’s 4th district also addressed the crowd at the rally. Having voted with Lappin against SWMP in 2006, he said the only difference five years later is the area now has two new schools within three blocks of the transfer site. But he acknowledged that in the past the burden of garbage facilities has been placed on other communities.

“We all need to recognize… that the burden of garbage facilities has been born by disadvantaged neighborhoods and the working poor. That is simply unjust,” Garodnick said, then, after a few stray handclaps in the crowd, “Let’s recognize that together.” The claps then grew into a full applause.

Are there alternatives?

Garodnick argued that the city was not correcting this injustice by doing the same thing to residents in the Upper East Side.

Lappin said in her speech that the area had already done their “fair share” by having had a waste transfer station before, and named alternative locations at Hudson Rail Yards and the tow pound at Pier 76, both on the West side of Manhattan.

However, the DSNY has deemed both sites to be technologically and economically unsuitable for the facility. The Hudson Rail Yards would have insufficient space to conduct site operations, would require the construction of tunnels below existing rail tunnels, and the rail lines to the north are not large enough for the necessary loads, Turso stated via e-mail. As for Pier 76, there would be insufficient vertical clearance for truck tipping points, the truck ramp would be too steep, and there would be inadequate emergency vehicle access, he said.

In working toward a goal of minimizing the amount of waste being transferred across city streets, the DSNY found other locations on the west side to be impractical, as they would require the waste of the east side districts to be trucked to the west side.

“We wanted to try to create, in the various waste sheds, opportunities for the waste to be traveling less distance, creating less traffic, tearing up fewer roads, and so the notion of taking the East side garbage across town doesn’t help as it only creates another problem, and that’s traffic,” Turso said.

On Tuesday, Upper East Side residents held another rally, this time on the Stanley Isaacs Plaza. While the first rally was held at Asphalt Green to represent its significance as a park, the second rally concentrated more on the issue of placing a waste station in a densely populated residential area.

Ratner says that while she supports the SWMP’s overall goal of environmental justice, she is not convinced that East 91st Street is the best location for an MTS:

“We understand the concerns of the environmental justice advocates. We empathize with them probably more than anyone else at this point. We really understand the way garbage needs to be dealt with in New York needs to change in a global way. We’d like to know from the speaker and the current mayor why this particular site… is the right place for a new trash facility.”