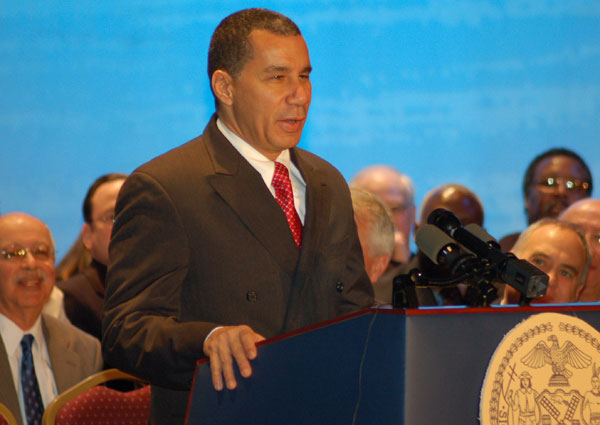

Photo by: Thomas Good

Gov. David Paterson’s administration is charting a new course in how the justice system treats underage prostitutes. But the state’s budget crisis could derail plans to replace punitive measures with services.

The day Naydeen met the man who would become her pimp, she felt like she’d found a fast-lane exit off a dead-end road. At 16, it had been eight years since she watched her father die and her family fall apart; one year since she’d run away from her mom. She was sleeping on friends’ couches, working part-time for minimum wage, feeling, she says, “just alone and lost. Then there’s this guy. He made me think he saw something special in me, like I could be a part of something.”

A month later, she was turning tricks on the street six nights a week, pulling in as much as $1,700 for a 12-hour stint—all but $20 of which she turned over to the man she now called “Daddy.”

Each year, more than 2,200 children end up in New York City’s commercial sex trade. New York state used to treat kids picked up for prostitution as juvenile delinquents, sending children as young as 12 to detention centers or lockups. At the beginning of this month, that practice changed: A law went into effect that redefines kids in the sex industry as victims of domestic trafficking. When they end up in court, judges are now mandated, in nearly all cases, to refer them to community-based crisis and counseling services, rather than sentencing them for sex crimes.

The problem is, if judges are supposed to send kids to services, then someone has to pay for those services. And the budget crisis in Albany is making it unlikely that the state is going to pay very much.

The new law, known as the Safe Harbor Act for Exploited Children, was originally passed in August of 2008, part of the state’s long-fought and hard-won shift toward providing kids who land in the criminal justice system with services in their home communities, rather than sending them to upstate lockups that critics from the federal government to advocacy groups have condemned as dangerous, violent and counterproductive.

“We’re talking about children who live under the control of an adult man whose sole purpose is to sell them for profit,” says Rachel Lloyd, the executive director of the New York organization Girls Education and Mentoring Services (GEMS), which works with girls and young women in the sex industry. “That person becomes their controller, their provider, their abuser, their everything. It’s very challenging to break that if you’re looking at them as criminals.”

Many underage prostitutes are homeless, surviving at the mercy of friends or the street, and nearly all of them have histories of abuse or involvement with the foster care system.

Naydeen’s experience reflects the vast power differential between pimp and child prostitute.

“He was like a father figure,” she says of him. “I guess I felt I needed somebody to control me, and pleasing him made me happy.” It wasn’t for nearly a year—after she’d been arrested three times and served a month in jail for prostitution—that she wanted out badly enough to risk running away. By that time, she says, “I knew a lot about him and I was scared he’d come after me and try to kill me.”

When Safe Harbor was written, it called on the state to develop a network of short- and long-term safe houses for kids trying to escape the sex industry, and to train police and other state agents to recognize and respond to sexual exploitation. “The idea was that programs would be up and running before the law went into effect this year,” says Katherine Mullen, an attorney with the Juvenile Rights Practice at the Legal Aid Society and one of the primary advocates credited with getting Safe Harbor passed.

But that was before last year’s leadership struggle in Albany and the intensification of the state’s budget crisis.

Last fiscal year, no money was allocated to creating new services under Safe Harbor. This year, when the state budget office estimated the cost of services mandated by the Act, they came up with a number of $10 million, which has been sliced down to $3 million in the state’s already-over-deadline, ongoing budget negotiations.

That’s enough money to build just a single long-term safe house, according to Assembly Member William Scarborough, who sponsored the act when it originally went through the legislature.

“These are hard economic times,” he says. “The key thing is to get it started, and to begin giving these young people the opportunity to reclaim their lives.”

But girls’ advocates worry that, without resources for counseling and crisis intervention, the state will be setting young people up to go right back to the lives they’re trying to escape. “This has to be a priority if it’s going to work,” says Lloyd. “New York has been at the forefront of change in the way the country responds to domestically trafficked youth. Folks are still watching and we need to make sure we do this well.”

For Naydeen, it was finding a place where she could talk about the life she had lived that helped her imagine a new one. At 24, after graduating from GEMS programming, she’s working for the organization as an administrative assistant and youth counselor, and she’s a year-and-a-half away from a bachelor’s degree in social work.

“I just hope that places like this can exist for other girls,” she says. “Change doesn’t happen overnight, but you have to know that there are people who love you and don’t want anything in return. Knowing other people who’ve been through it—that makes you see that it’s never too late to leave.”