The Riverdale/Osborn Towers in East New York, four brick buildings arrayed around two concrete walkways, are as drab and unwelcoming as any high-rise housing project. Inside, however, hides an unexpected treasure: cozy, low-ceilinged offices festooned with colorful posters and banners. This is the home of MUGAMA, an organization founded to stitch together and support the scattered members of one small and obscure Caribbean ethnic group, the Garifuna.

“To tell my people that nothing is impossible, that the American dream is attainable–that has been my goal,” says Dionisia Amaya, one of MUGAMA’s founders.

Amaya’s people are the Garifuna–a marginalized ethnic group in Honduras and Belize that has quietly settled in New York City over the last 60 years. MUGAMA, which stands for Mujeres Garinagu en Marcha, or Garinagu Women on the March, aims to help Garifuna New Yorkers succeed in their new country. (Garinagu is plural for Garifuna.) In borrowed classrooms at schools in Brooklyn and the Bronx, MUGAMA offers GED and English instruction, and provides small college scholarships.

The organization offers something else, too: A means for a speck of 50,000 people among New York’s welter of immigrant groups to find a balance between the need to assimilate and the desire to preserve a distinct cultural heritage.

On April 12, MUGAMA is holding its annual celebration of that heritage and the unlikely events that ultimately brought the Garifuna to New York. More than two centuries ago, their ancestors waged a 40-year war with the British, who tried and failed to enslave a group of Africans on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent. The British, unable to subdue these feisty people, drove them off the island instead, giving rise to the Garifuna’s proudest moment. They celebrate Garifuna Survival Day with music, dance and commemoration.

These festivities bring Garifuna from different countries together, says Felix Miranda, an expert on Garifuna history who works as an administrator for the New York City Transit Authority. That way, this minute ethnic grouplet prevents its identity from being “watered down,” he says.

New York’s Garifuna are well aware that most New Yorkers don’t know anything about their culture or even that they exist. Being part of a tiny group in a big city isn’t easy. “The United States believes in numbers,” Miranda observes. “The greater your voice is in the city, the greater the chance is of getting things done.”

Isidora Benedith of the Bronx agrees that invisibility is difficult. “I see many very large groups of people who can move the city with parades and all that stuff,” she says. Benedith volunteers teaching a GED preparation class for MUGAMA, with the idea of helping her people take some of their first steps toward visibility and power. “I think we are almost anonymous people doing small things. But it’s worth it,” she laughs.

_______

Garifuna first came to New York in the 1930s. A seafaring people, they arrived as merchant marines during World War II. Today, they live in the South Bronx, eastern Brooklyn and Staten Island.

Most first-generation Garinagu have footholds on the first rungs of the economy, working in long-hour, low-pay jobs like home health care, housekeeping and construction. The children of earlier waves work as school teachers, police officers and other professionals.

But until three teachers founded MUGAMA in 1989, New York’s Garifuna did not have an institution to tie them together. They have no restaurants, shops or community centers of their own where people can gather.

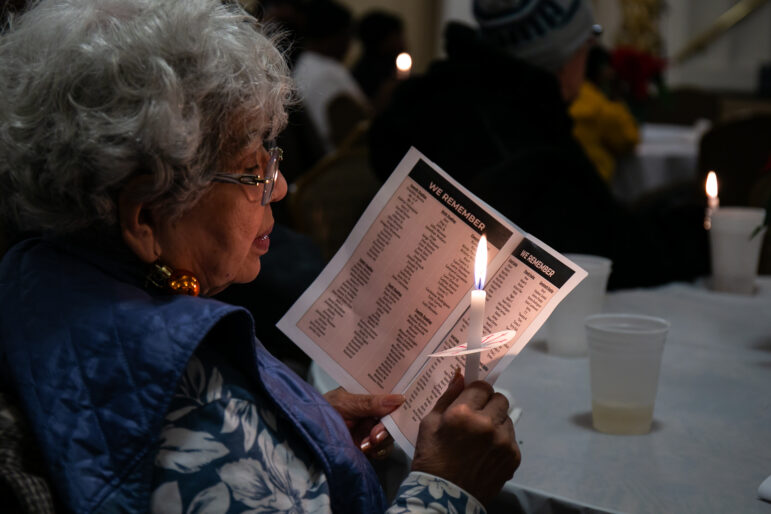

“This is our acculturation,” Amaya shouts over blasts of furious percussion at a February benefit for MUGAMA’s scholarship fund, held at a Jamaica, Queens, banquet hall. She motions toward the women gathered around her, all wearing formal dresses as they dance to a live band playing traditional Garifuna music.

Nearly 150 guests danced until 3 a.m., with couples young and old taking the floor, laughing. The women were invited to model their dresses for the crowd, forming a conga line fashion show. Over the loud music rose shouts in Spanish and Garifuna–a mix of African Bantu, English, Spanish, Portuguese and French.

Like any immigrant group, the Garifuna have to make hard choices between preserving their heritage and embracing assimilation. In their history, they have a particularly compelling reason to look both ways, into both the past and the future.

Garifuna ancestors include Bantu tribespeople brought to St. Vincent by British slave-traders. There, the Bantu surprised their captors by taking refuge with the island’s indigenous residents, with whom they soon intermarried. Though the British spent decades trying to enslave the Garifuna, their attempts failed bloodily. In 1797, the British threw them off the island.

“They couldn’t stand that this group of people refused to be controlled,” says Amaya proudly. “So they decided to deport us.”

After a long sea journey, most ended up in Honduras, while others settled in Belize and Nicaragua. There, they faced marginalization, discrimination and worse. In 1937, a government-backed massacre tore through Honduran villages. More recently, officials have used Hurricane Mitch as an excuse to displace Garifuna from beachfront areas with lucrative tourism potential.

“We need to get a better understanding of what these people suffered,” Miranda says. “When you think about the little things we take for granted, you begin to realize how important that is.”

_______

MUGAMA’s attempts to reach out to Garifuna New Yorkers are essential to maintaining the community’s cohesiveness, says J.A. George Irish, director of the Caribbean Research Center at Medgar Evers College. “[MUGAMA] are very well organized, and they are community-based,” Irish says. “They have a strong sense of connection with the average working-class person. They are not one of those paper-based groups.”

Despite their perseverance, New York’s Garifuna still face difficulties common to immigrant groups, including financial struggles, language barriers and jobs with little room for advancement. MUGAMA was founded to offer them a better chance.

Amaya, a retired guidance counselor with a master’s degree from Brooklyn College, wanted to see other Garifuna succeed in the U.S. The most important step toward that, she says, is education.

With this organization, “we are opening up to any woman who wants to excel,” Amaya says, “and help our community, especially our youth. I wanted to tell [other Garinagu] that if I was able to achieve all of these goals, everybody else can.”

MUGAMA began with next to no resources or experience. When it was first starting up, the group met in Amaya’s Brooklyn basement and used her home answering machine to take the organization’s phone calls. Its English as a Second Language and GED classes, offered mainly on weekends, are still taught by teachers working pro bono, help Amaya says is becoming harder to find. The organization’s small budget, she says, prevents MUGAMA from offering as many classes as they had hoped.

The group hopes to expand to offer social services like employment aid and health information. It has grown slowly, however, not unusual for a grassroots organization serving lower-income people. Since 1996, MUGAMA has been largely funded by a grant from the New York Foundation, which provides $35,000 of the group’s roughly $40,000-a-year budget.

Maria Mottola, a program director for the foundation, says she was impressed with MUGAMA’s ability to remain close to its base. While the organization used the bulk of its funding to hire a staff coordinator, it continues to be led and run almost entirely by volunteers.

Mottola says that Garifuna were much more comfortable getting services from organizations staffed by people from their own community. “MUGAMA is filling a need that larger groups don’t,” she says. “It is their own organization: They are the leaders of the organization, the founders of the organization and the staffers of the organization. They are serving members of their own community–that’s where their strength is.”

As they become more integrated into city life, New York’s Garifuna are increasingly aware that they have to work to keep their culture and language alive.

“Assimilation is always there,” says Jos