While New York has secured eight offshore wind contracts for development, energy experts say not enough investment is being made in the port infrastructure needed to assemble the turbines and deploy them out to sea.

Courtesy South Fork Wind

South Fork Wind under construction off the coast of Long Island. The project will be the one of the first large-scale offshore wind farms up and running in the United States.New York has big plans to generate power from non-polluting renewable energy, produced by giant windmills floating in the Atlantic ocean.

The goal, put forth by the state’s 2019 climate law, is to develop 9,000 megawatts of offshore wind power by 2035 and help the state move away from fossil fuels that contribute to global warming. That’s enough energy to power 6 million homes and cover 30 percent of the electricity load, according to the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA).

While New York has secured eight offshore wind contracts for development, energy experts say not enough investment is being made in the port infrastructure needed to assemble the wind turbines and deploy them out to sea.

“I don’t think we are moving fast enough or investing enough [in the ports],” said Robert Freudenberg, vice president of energy and environmental programs at the non-profit Regional Plan Association (RPA). “If we don’t start moving more sequentially and in a timely manner, then the next great bottleneck in getting offshore wind projects off the ground will be the ports.”

The local offshore wind industry has faced other setbacks this year, as projects have become increasingly expensive thanks to inflation and supply chain hurdles brought on by the pandemic. When renewable energy developers sought financial relief from the state, New York’s Public Service Commission (PSC) refused a request for $12 billion in funding, arguing it would drive up energy costs for consumers.

Still, environmentalists are hopeful that the time has come for New York-sourced wind energy to make its debut in the national market. South Fork Wind, a Long Island-based project a decade in the making, is set to go fully online early next year and will become one of the first large-scale offshore wind farms operating in the United States.

The U.S. currently uses up only 42 megawatts (MW) of offshore wind power. By comparison, Europe uses 28,000 MW and China 27,000 MW, according to the New York League of Conservation Voters.

“This is a major transition and it’s historic. When you change the way you produce energy for the first time since the Industrial Revolution, it’s going to take a lot of work and a lot of effort by a lot of people,” said Adrienne Esposito, executive director of the Citizens Campaign for the Environment.

“I think we can achieve [our climate goals], but it’s not going to be easy,” she added.

What about the ports?

Getting a wind farm up and running in the ocean is no easy feat.

When giant turbines located offshore capture high speed winds and spin, they produce electricity that is transferred to power stations on land through cables underground.

But these massive structures need to be assembled in a port near the waterfront so they can be easily shipped out to sea standing up. It’s imperative that they be located far away from any bridges, to guarantee the massive structures enough clearance to pass.

And right now, New York doesn’t actually have its own offshore wind port.

Instead, the Empire State has been relying on a port in New London, Connecticut to service projects like South Fork Wind and Sunrise Wind to the east of Montauk. The arrangement works for now, as the Connecticut port is conveniently close to where these wind farms are located on the ocean.

But companies that are trying to build out these ports in New York say the state may fall behind if it doesn’t invest in development on its home turf.

“Eventually, Connecticut will have several gigawatts of its own projects coming online and they’re going to become the priority. So New York has to have its own ports if it expects to meet any of its [climate] goals,” said Charles Dougherty, the chief commercial officer at Atlantic Offshore Terminals.

The company is building a port located in Richmond Valley, Staten Island, known as the Arthur Kill Terminal, which hopes to become a construction hub for New York’s offshore wind projects in the coming years. The proposed 32-acre wind turbine assembly facility is set to become operational by mid-2026, and will be the only offshore wind staging port in New York located outside the restrictiveness of bridges.

“If you don’t have assembly and staging ports of your own, you’re going to be significantly hamstrung in developing a domestic supply chain, and that means you’re going to be losing out on investments and job creation in New York,” Dougherty added.

The Arthur Kill Terminal received $48 million in federal funding in the fall of 2022. But the port’s developers say they need more financial backing and that state funding for the project has fallen short.

At the end of October, Gov. Kathy Hochul promised to set aside $300 million for companies manufacturing parts used in offshore wind farms upstate near New York’s capitol in Albany.

Hochul’s investment is set to create 1,700 direct and indirect jobs and supply almost one-third of the total regional demand for offshore wind by 2035, according to a spokesperson for NYSERDA.

But Dougherty says the new round of funding failed to include any money for “downstate port infrastructure.”

And although New York has made a total of $400 million in commitments to build out ports—the $300 pledged by Hochul, plus $40 million for the Port of Albany and $60 million for the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal—that money is yet to be distributed.

“As it stands today, New York doesn’t have the port capacity that it needs to build nine gigawatts of wind power by 2035,” Boone Davis, president and CEO of Atlantic Offshore Terminals, told City Limits.

“It’s critical that New York moves forward quickly in developing its ports, if it’s going to achieve its offshore wind goals,” Davis added.

One step forward, two steps back

The Arthur Kill terminal developers aren’t the only ones worried about the future of offshore wind, as inflation has hiked up the cost of executing these projects.

On Oct. 12, when the Public Service Commission refused a request for a financial boost that would help get 90 renewable energy projects off the ground, developers were sorely disappointed.

A couple of weeks later, the offshore wind developer Orsted pulled out of building two projects in New Jersey, sending shockwaves through the industry again, as proponents feared New York-based projects would suffer a similar fate.

To soften the blow, Gov. Hochul gave offshore wind companies a chance to re-do their budgets and rebid their contracts with the state. This new expedited bidding process, announced on Nov. 30, gives developers until Jan. 25 to submit their revised proposals.

But environmental experts warn that the new bidding could unearth another set of issues.

“If the companies go back and present numbers that work for them and it doesn’t align with what the state is comfortable with, it could lead to a situation where there is a misalignment and companies pull the plug all together,” said Robert Freudenberg of RPA.

At the very least, back and forth negotiations between bidders and the state could lead to further setbacks, environmentalists point out.

“The whole thing is going to cause some delay. And that means that people are going to live with [polluting] peaker plants in their communities for longer,” said David Alicea, New York field manager at the environmental group Sierra Club.

“I want to remain optimistic, but I think there’s a record in New York of putting out big climate goals and contracts and then facing challenges in actually getting things up and running,” Alicea told City Limits.

Just 27 to 29 percent of the state’s electricity currently comes from renewable energy, a far cry from the goal of New York’s climate law, which calls for 70 percent by 2030.

This fall, New York hit another roadblock, Alicea says, when Gov. Hochul vetoed a bill that would have allowed the major offshore wind project Empire Wind to connect its windfarm to the grid and power 1 million New York homes.

The bill would’ve circumvented a local rule to allow a transmission cable to run underground through a stretch of public beach. But the legislation saw opposition from local residents and Republican lawmakers who claimed it would disrupt tourist revenue during construction, produce carcinogenic electromagnetic fields and kill local wildlife.

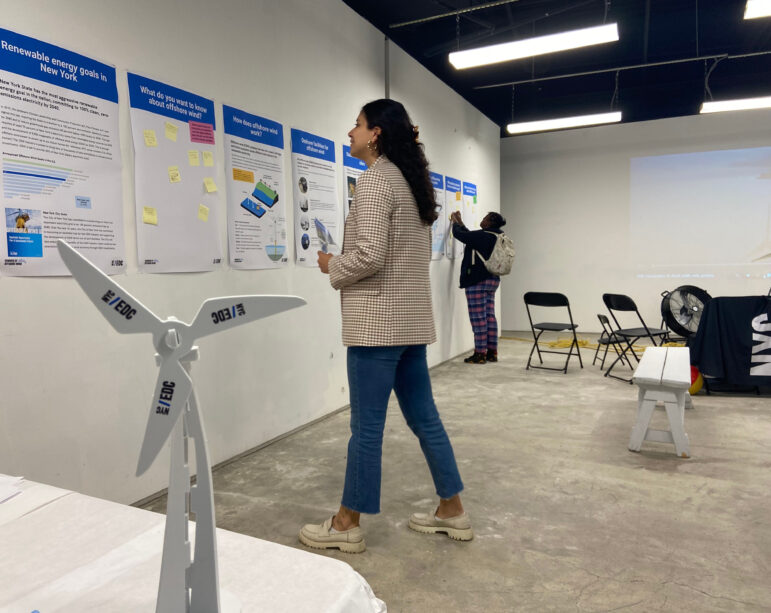

Mary Cunningham

NYCDEC held a “Summer of Offshore Wind,” event series inside the Staten Island Ferry terminal to educate and engage Staten Island residents as the borough emerges as a potential hub for the industry.Hope for the future

Despite these setbacks, New York made strides on its offshore wind plans this year.

On Oct. 24 Hochul announced that the government had selected three new projects for development.

According to a press release, these ventures would yield a total of “4,032 megawatts (MW) of clean energy” and nix over 7 million metric tons of CO2 from the atmosphere annually, which is equivalent to “removing 1.6 million cars from the road each year.”

The announcement, which came shortly after developers were denied extra subsidies for their projects, signals continued political support for offshore wind in Hochul’s government, environmentalists say.

The year also came to a close with South Fork Wind delivering power to Long Island for the first time. The project has installed its first five turbines, and the developer expects to have all 12 completed by early 2024.*

Julia Bovey, head of external affairs for one of South Fork’s developers, Eversource, says that despite all the challenges, there is reason to celebrate.

“There have been a lot of articles written in the last month about these headwinds that offshore wind is facing and I know that has a lot of people feeling uncertain,” Bovey said. “But I hope that seeing South Fork go online will really be a sign that we can keep going, that there is a light at the end of the tunnel and that these [projects] can happen and we’ve just got to keep them coming.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Mariana@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

*This story has been updated since original publication to correct the expected timeline for when South Fork Wind would be fully operational.

One thought on “Will New York Meet its Goals for Offshore Wind Power?”

As reported here, “Gov. Hochul vetoed a bill that would have allowed the major offshore wind project Empire Wind to connect its windfarm to the grid and power 1 million New York homes.” Why? Because of both deliberate disinformation and credulously recirculated misinformation from fossil fuels industry propaganda fronts and local media outlets – which makes our risk-averse Governor’s veto all the more disturbing. Burying power lines under beaches and harbors is both safe and essential to connecting wind farms offshore to consumers onshore. How does that executive decision square the NY State commitments to invest $400 million+ in new port facilities for the wind power industry? Is that why the promised $60 million for the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal windpower support center “is yet to be distributed?”