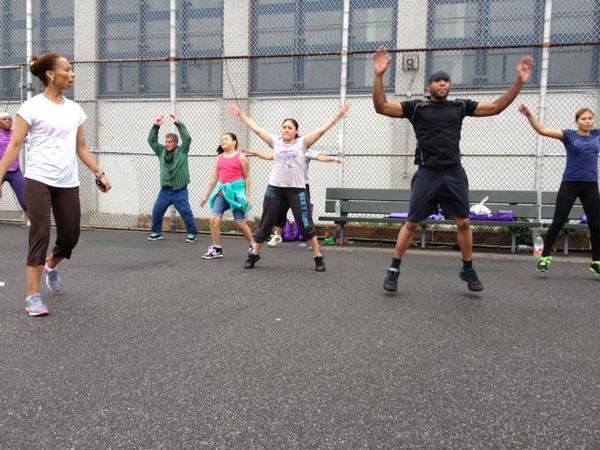

Photo by: Tobias Salinger

Yvanna Nazaire leads her aerobics class in jumping jacks on a Saturday morning in Bushwick. Her class is part of a Beacon program at IS-291.

At a Saturday morning aerobics class in Bushwick, fitness instructor Yvana Nazaire makes gentle fun of her exhausted students to urge them on in a series of leg lifts.

“Look at it this way, you’ll take a nice nap,” says Nazaire. “The television will be watching you.” The 13 women and two men of varied ages in the workout laugh but groan later as their instructor leads them in laps around the park and dips against a bench.

Nazaire’s popular family fitness program through a Beacon center at IS 291 is part of a movement by city government, community organizations and neighborhood residents to attack chronic health problems through nutrition and exercise.

Bushwick and nearby Bed-Stuy are the primary communities served by one of three district public health offices set up by the city in 2003 to conduct research, design programming and implement joint preventive health efforts.

“The obesity problem in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick is part of an epidemic affecting Brooklyn, New York City and the nation,” concludes a 2007 report by the North and Central Brooklyn district office.

Another pamphlet circulated by the office that year was a nine-month study on the eating habits of a dozen Latino families in Bushwick. Noting that there were 131 bodegas in Bushwick and only 10 supermarkets, the report recommends enlisting corner stores in what would later become the city’s “Healthy Bodega Initiative” and greater educational programs around eating well on a budget.

But diabetes and obesity rates in the areas targeted by the district office actually increased during the period since the reports came out in 2007 to the latest health department figures in 2011—from 11.3 percent to 14.6 in diabetes and from 29.2 percent to 35.1 in obesity.

The numbers make it hard to say whether the noticeable effort by the city to change dietary habits in the neighborhood has led to better health. But it’s not just about food. The lack of local options for exercise, which experts cite as an essential companion to nutrition, may be inhibiting Bushwick’s ability to get and stay fit.

City’s efforts focused on food

The Bloomberg Administration’s manifold preventive health effort to make fresh produce more available focuses on Bushwick’s markets, corner stores and groceries.

Sea Town supermarket on Linden Street expanded in 2011 with help from a Department of City Planning policy that eases parking and permit requirements for large grocery stores in neighborhoods deemed to be lacking them. Two area delis have fruit and vegetable displays in the front of the store thanks to the bodega program, and a 2010 report from the health department notes the program has helped 520 stores citywide make connections with affordable local sellers and conduct programs aimed at encouraging healthy eating habits. Sea Town recently hosted an event with students from the nearby Bushwick Campus garden to share yogurt and granola recipes and samples with Saturday shoppers.

“It teaches people,” says Jim Cepeda, a store employee. “While we were giving out the parfaits, we were handing out flyers and everything.”

EcoStation:NY runs six farmers markets and two community gardens in Bushwicks. Founded in 2009 by Sean-Michael Fleming and Travis Tench, the social justice and agriculture education group partners with the district health office on projects like the Bushwick Farmers Market at Maria Hernandez Park. He says the weekly market has proven successful with local residents.

“New vendors are able to come and they’re able to stay—that’s a testament to it,” says Tench. “Today the market is as big as it’s ever been.” He was watering locally-grown veggies with a spray bottle and posting on social media about new developments at the market like an Indian food table on a recent Saturday.

A few tables over, Erika Brenner of the Wassaic Community Farm sells tea, herbs and vegetables. She says low-income city dwellers often develop health problems and “get locked in the system” due to a lack of available fresh produce.

“Food justice ties into a larger systemic issue that is playing out in this country,” says Brenner. “Iniquities are present and food is no different.”

Impact hard to measure

City “green carts” selling fruit next to subway stations and busy intersections are another visible part of the effort, but it’s difficult to discern what impact these measures have had on fruit and veggie consumption. Bushwick is one of the “underserved” areas where vendors may apply for public-private financing, but a 2011 report on the fruit stands found that the number of Bushwick residents who said they hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables the day before is almost five percentage points higher than the average for neighborhoods without the carts. (The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene declined requests to comment for this story.)

But that doesn’t mean efforts to make good produce available have gone unnoticed or in vain, as shown by the Saturday market at Maria Hernandez. Representatives from the health department’s Stellar Farmers Markets program set up informal classrooms and dole out samples of homemade beet salad on either end of the market. In one tent, a dozen or so shoppers gather to listen to money-saving tips and dietary advice in Spanish while groups of children sit in the other one guessing what fruits or vegetables are inside a series of brown bags. All participants receive vouchers to buy fresh fruits or vegetables.

“Here it is easy to find them, but at the supermarket, not so much,” says Modesta Nuñez, 68, through an interpreter. She had purchased celery stalks, cucumbers and beets she said she would later serve to her grandchildren.

EcoStation runs markets at locations such as the Academy for Environmental Leadership’s community garden on the Bushwick High School campus and a new partnership green spot begun this year on Broadway and Grove Street, next to the Make the Road New York headquarters. The Maria Hernandez market, with Brenner’s assortment of chard and burdock tea—which she notes is a traditional high blood pressure salve—and the heaping piles of lettuce, cabbage and broccoli Roberto Pavia brings each week from his family’s farm in New Jersey, caters to both longtime Latino residents and new arrivals.

Tench says EcoStation is “trying to create a common ground for people and creating a place for people to come together to talk about health or social issues.”

Exercise: a missing ingredient?

The federal Centers for Disease Control’s division of nutrition, physical activity, overweight and obesity recommends both regular exercise and a healthy diet to prevent or mitigate chronic disease, and both the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association note the importance of such preventive measures on their websites. One area pharmacist who says a majority of the prescriptions at his store are for diabetes and heart disease medication says he counsels customers to pair their medicine with vigorous exercise.

I tell them ‘you gotta sweat,'” says Abie Alkada of Fine Care Pharmacy on Broadway. “You can’t just be walking around.”

The aerobics program led by Nazaire at the Beacon center has been convenient to attend for its roughly one hundred participants. Zorana Innis says she likes the Nazaire’s workout class because it’s atypical in Bushwick.

“I’ve been in the community for 27 years and I’ve never seen anything like this,” says Innis, who has attended Nazaire’s class for two years.

City Department of Youth and Community Development spokesman Mark Zustovich noted the agency awards contracts to organizations such as the Coalition for Hispanic Family Services, which operates that Beacon center that hosts Nazaire’s class, for after-school programs like tutoring, cultural studies and recreation at 80 sites throughout the city.

Innis was one of three dozen people who showed up outside the Coalition’s headquarters on Wyckoff Avenue to protest when a staff member told them earlier this month that Nazaire would no longer teach her fitness classes from IS 291.

Demonstrations outside both the school and the Coalition’s headquarters led Denise Rosario, the executive director of the Beacon’s contracted sponsor, the Coalition for Hispanic Family Services, to meet with a group of the program participants. She said Nazaire’s well-attended, but not full, class will be back in its entirety in the fall. Budgetary concerns centering on a new “Zumba” class taught by a different instructor had prompted the director of the Beacon center to tell Nazaire’s class that the class would be cut, but Rosario said that the coalition is “fully committed” to health in Bushwick. She said she admires Nazaire’s success in getting women of all ages to participate.

“Sometimes, particularly with women, we are more occupied with taking care of everyone else first, and we forget to take care of ourselves,” she says. The coalition’s website notes its operations serve 3000 children and their families in North Brooklyn and Queens through foster care management, mental health programs and homelessness prevention.

Rosario said the neighborhood still has a dearth of preventive health care.

“We need a lot more providers that speak the language and understand the culture so that we can have a greater impact on the Bushwick community,” she said in a phone interview.

Facilities like those of IS 291, which also has a weight room, are precious in a community not noted for its park and recreational facilities. Bushwick does not have a city-funded recreation center. The Department of Parks and Recreation’s fiscal 2013-14 statement of needs states the agency’s intention to buy a small 0.7-acre plot for parkland in Bushwick in an effort aimed at “addressing the community’s open space and recreational needs.”

The facilities currently available are lacking in quality, according to studies and local officials. New Yorkers for Parks gave Maria Hernandez, Bushwick’s largest park, a grade of 70 percent on its most recent report card due to a dearth of drinking fountains and “active recreation space.”

Conditions at Hope Ballfields, the home to several baseball and softball leagues, came up at a July 22 press conference against gun violence organized by Make the Road and area pols. U.S. Rep. Nydia Velázquez paused from her discussion of neighborhood safety and gun control legislation to draw attention to the splotchy outfield grass and dilapidated conditions of the park behind her. “I would invite you to show me one in Manhattan that looks like this,” she said. “That will show you how much investment the city puts in low-income neighborhoods.”

Residents who do have funds available to invest on their exercise are able to get low-cost memberships at private gyms. Both Planet Fitness and Richie’s Gym offer rates starting at $20 per month at each of their two locations in the area. Though George Llorens, the manager at Richie’s, can only think of one other gym in the neighborhood besides those four, he says the number of facilities is sufficient.

“There’s enough, but there’s not enough motivation,” says Llorens.

Nazaire does her best to instill that inspiration among her students. Thirteen women and two men of varied ages who show up to a Saturday morning workout at a more modern-looking track and playground by IS 296 laugh at her constant jokes but groan later as their instructor leads them in laps around the park and dips against a bench.

Nazaire, who said she has lived in Bushwick for 15 years, first began leading neighborhood aerobics workouts when she would practice her fitness routine while her daughter played in a nearby park. A student of hers named George Sosa credits her for helping him lose 100 pounds and says she calls him when he doesn’t show up to class. But she says it is Sosa and his classmates of ages “as young as 5, as old as 80” who keep her going.

“After I started working with this population, I got attracted,” says Nazaire. “They come with their family and they bring a positive attitude.”

Sosa spearheaded the successful effort to maintain the exercise program at IS 291, though Nazaire indicated she would have found some way to continue her classes. She and everyone working to promote healthy living in Bushwick are up against challenges. But Sosa said he urged for Nazaire’s physically-taxing workouts to continue because he understands their value to his health.

“It’s not so much something that I really enjoy, but it’s good for me,” said Sosa.