With delayed timelines and ongoing construction, Red Hook residents are still living in limbo as they wait for a $568 million resiliency project to come to life, more than a decade after Sandy slammed the complex.

Adi Talwar

NYCHA Red Hook resident Henry Watkins amidst construction fencing on the public housing campus on Oct. 23, 2024.When Hurricane Sandy ripped through New York City in late October of 2012—leaving 43 dead and $19 billion in damages—it struck a blow to NYCHA’s Red Hook Houses, a 40-acre complex nestled into Brooklyn’s western waterfront.

The storm hit the 1930s era development, destroying roofs, the senior center, and ravaging electrical systems and boilers, which led to weeks of power outages.

But 12 years later, plans to recover and flood-proof the complex are yet to be completed. Residents are sick of living in a perpetual construction site where former green spaces have become hard-hat zones, disrupted by the sight of rubble and excavators.

“You can’t walk across anywhere to get to anywhere,” said Red Hook Houses resident Henry Watkins.

Strolls across the campus were easier when there were clear pathways, and Watkins and his neighbors remember a time when various species of tall trees towered over the courtyards surrounding their home. Hundreds of them are now gone to make way for new construction.

To top it off, constant dust, fenced off areas, and even the risk of hazardous leaks when gas lines accidentally get hit during construction, are a part of daily life.

Adi Talwar

A sign on a construction fence outlining the resiliency work underway at NYCHA’s Red Hook Houses.Residents say NYCHA, which is in charge of the plans, isn’t doing enough to keep them informed about what is really happening on site, and say they want to participate more in the decision-making process.

“We’ve been demanding transparency from NYCHA,” said Tevina Willis, a resident and senior manager of community organizing at the nonprofit Red Hook Initiative. “But tenants are still left out of the loop.”

The project has also been marked by delays. The deadline for completion of construction, which only began in 2017, is two years behind its pre-pandemic schedule. NYCHA promises to finish in the second quarter of next year and says delays are warranted because Red Hook Houses—a massive development home to more than 6,000 tenants that includes both East and West wings—is the agency’s largest and most complicated Sandy recovery project.

But work to safeguard Red Hook and other NYCHA developments from future storms has been historically slow. Of the 35 NYCHA complexes across the city that were awarded $3.3 billion in 2015 from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for post-Sandy repairs and flood-proof work, 10 are still under construction.

And larger city-wide plans to barricade the entire Red Hook neighborhood with flood walls and gates are yet to leave the drawing board, despite the mounting impact of climate change as it ushers in more severe storms.

“It’s really hard to continuously advocate for [resilience] if the city is not doing a good job of moving these projects forward quickly and in the right way. It actually makes it harder to bring more of these projects to life in other parts of the city,” said Tyler Taba, director of resilience* at the Waterfront Alliance.

Adi Talwar

The walkway to 484 Columbia St. in NYCHA’s Red Hook apartment complex, surrounded by resiliency-related construction.“Out of the loop”

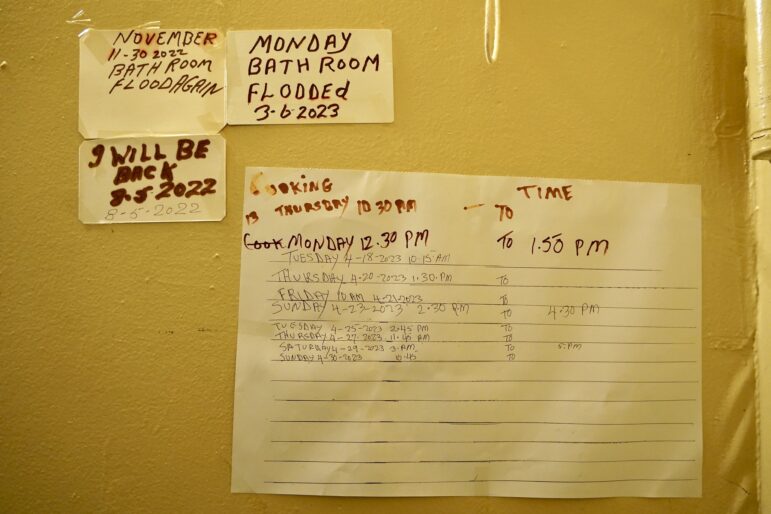

In January, Andrea McKnight smelled a pungent odor in her building in Red Hook West. Within moments, she saw first responders in front of her building. A neighbor informed her that construction workers accidentally hit the gas line, causing a disruption that lasted months.

“Things happen,” said McKnight. “We got hit with the gas but it wasn’t in their plans.”

Lots of other things have happened that NYCHA didn’t foresee. At one point, a contractor the agency hired to rehabilitate the Sandy-ravaged Senior Center was the subject of a city-led probe into why work was failing to progress on site, despite the contractor jacking up project prices.

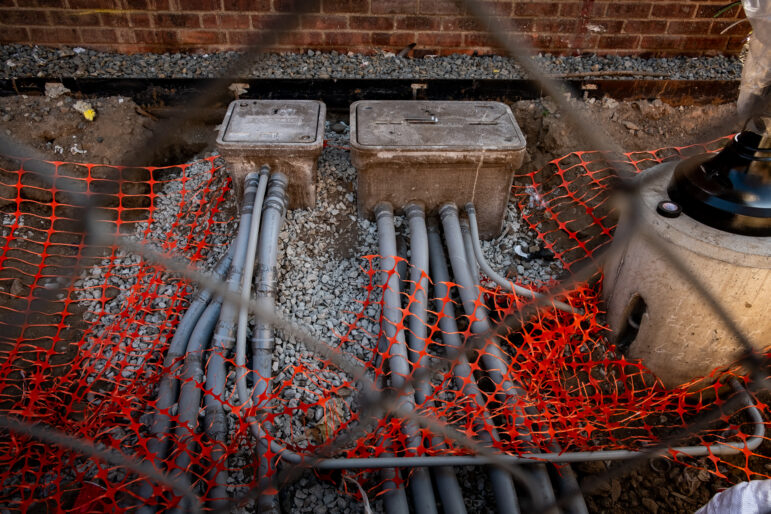

And replacing the 21 boilers damaged by Sandy and creating a separate flood-proof space for new ones proved to be a major design challenge, given the limited square footage they had to work with, NYCHA told City Limits in an email.

While hurdles are expected on a project of this magnitude, letting residents in on the setbacks hasn’t been NYCHA’s strong suit, tenants say.

“When a notice is put up, it’s small, it’s not clear. They put a notice up the day a [power] outage is happening. So people can’t plan ahead of time,” said Willis.

Most of the information about what is happening with construction is passed on to tenants through what NYCHA calls,a “dedicated liaison,” or a community leader who is responsible for spreading the word. These liaisons are tasked with attending community meetings and warning people about disruptive construction activities.

Adi Talwar

Construction workers in front of 82 Dwight St. in NYCHA’s Red Hook apartment complex.Residents can also sign up to get email updates using this form, which is buried deep at the end of an “engagement tab” on NYCHA’s Recovery and Resiliency website. And there is a hotline listed at the foot of the same page, though it failed to give basic information about how to register for updates when City Limits called.

NYCHA told City Limits in an email that it has done plenty of outreach in the community since 2014, hosting over 200 meetings, making over 76,000 calls and distributing nearly 27,000 flyers.

In the loop or not, tenants are eager to see results since the pandemic hit and the promise of a 2022 completion date got pushed to the rearview mirror.

Still, NYCHA says it’s been making great progress as $485 million of the $568 million Red Hook Houses received from FEMA has been spent so far. The agency also told City Limits that other funds from the city and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) have been poured into the site over the years.

The money is paying for a wide range of work, including creating elevated courtyards called “lily pads” that will serve as a natural barrier for stormwater. Separate annexes that house mechanical, electrical and plumbing equipment were also built above flood levels. Generators, boilers and roofs were replaced, and damaged playgrounds were restored.

While these improvements are welcome by tenants, many feel left out of the decision making process altogether. Danielle Fludd, a resident of Red Hook West houses and Environmental Justice Fellow at Red Hook Initiative, wanted sprinklers to be added to the playground to cool her two kids off in the summer.

Adi Talwar

A courtyard with play area in front of 38 Bush St. in NYCHA’s Red Hook apartment complex.“They did what they wanted to do for our community, but they didn’t really go and ask people what we actually need,” Fludd said.

Delays on all fronts

In the days leading up to Sandy, Watkins remembered getting everything he thought he needed: batteries, candles and bottles of water. He recalled some of his neighbors doing the same, but at the time they were not aware of just how severe the storm would be.

“In your mind, you’re thinking ‘it isn’t going to be that serious,’” Watkins said,

But when Hurricane Sandy landed on Oct. 29, 2012, storm water rushed into the basements of the Red Hook Houses where the boiler and electrical systems were placed, and caused a power outage for thousands of residents.

Something as routine as charging a phone became a hassle and for tenants, particularly seniors living on higher floors, going outside was difficult without reliable elevator service. “We weren’t prepared for the storm, and that’s where it got crazy,” Watkins said.

Three years later, when former Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that FEMA would be injecting $3.3 billion into helping the 35 public housing developments hardest hit by Sandy bounce back from the tragedy, it was seen as a major game changer.

NYCHA called it “the largest infusion of funds into public housing” since the agency was created in 1935. As of this August, $3.1 billion of the disaster recovery funding has been spent and work on 22 of the 35 developments are mostly completed, NYCHA told City Limits.

But it took more than a decade to get to this point. The start of construction was reportedly delayed in 31 of the 35 developments ravaged by Sandy, in most cases, by a year or more.

The City Comptroller’s office noted in a 2022 post-Sandy report that delays and “lack” of “progress” affected “the safety and comfort” of NYCHA resident’s homes across the boroughs. Resilience work has been especially slow-moving in Red Hook.

Adi Talwar

Construction underway at NYCHA’s Red Hook Houses.“Residents at Red Hook Houses waited nearly 5 years for NYCHA to begin groundbreaking on essential repairs to their buildings’ boilers and roofs,” the Comptroller’s report points out.

And a $100 million plan to build floodwalls, deployable flood barriers and raise the street level in key areas to protect the entire Red Hook neighborhood from flooding is still in the design phase, according to the Department of Design and Construction.

Meanwhile, Mayor Eric Adams recently celebrated the completion of phase one of the East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) project, another plan to build flood walls and gates along Manhattan’s Lower East Side from East 25th Street to Montgomery Street.

The mayor promised not to leave “anyone behind” and conclude similar resilience measures in other parts of the city at a press conference in mid-October. “That includes Red Hook [in] Brooklyn and other neighborhoods that are vulnerable to the effects of climate storms,” Adams said.

But there have definitely been more investments made on one side of the bridge than the other, Taba from Waterfront Alliance says.

While $7 billion will be poured into safeguarding the financial district from storms in yet another venture known as the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency (LMCR) Project, Taba says it’s unlikely that something of that magnitude would happen in Brooklyn.

“Are we going to get that scale of a project in Red Hook, or Gowanus or Coney Island, or Canarsie? I would love to think that we will, but I don’t know that the city will make that level of investment [in those communities],” Taba said.

Red Hook’s own Coastal Resiliency Project, which officials say will protect it from 99.9 percent of all coastal storms, was only approved by City Council in June of this year, with construction set to be completed in 2028.

In an email, the Department of City Planning downplayed the delay in getting Red Hook’s project off the ground when compared to the other two Manhattan initiatives. The Department said the Red Hook flood walls have a shorter timeline for construction than the other Manhattan-based projects, and will be completed in the same year as LMCR.

In the meantime, the neighborhood remains at risk. Red Hook is surrounded by major waterways, and the lowland area is predicted to have a “major risk of flooding” over the next three decades, according to First Street, a company that measures climate risks in the United States.

Adi Talwar

October 23, 2024: 791 Hicks Street in NYCHA Red HookDuring Sandy, 740 properties in the neighborhood were affected, according to First Street. And over the next 30 years, 1,159 are at risk of flooding—representing 99.3 percent of structures in Red Hook.

While residents wait for the planned infrastructure to become a reality, there are some temporary flood protection measures in place. For instance, aluminum panels have been placed in strategic openings in neighborhood buildings to protect boilers or electrical rooms, and tiger dams—giant orange inflatable tubes filled with water—line the coast to help barricade it from floods.

Although the New York City Emergency Management Department told City Limits these solutions should be “short term” as they don’t “fully eliminate flood risks,” a permanent solution is still a long way away.

These are “massive, complex projects that take years to design and years to build,” the Department of Environmental Protection’s commissioner, Rohit Aggarwala, said in April. While he promised that “several” of these will be delivered “within two to three years,” he admitted that “none are complete and fully functional” yet.

“The reality is that this year, if a storm surge hits New York City, there will be flooding,” said Aggarwala.

*This story was updated to reflect Tyler Taba’s new job title.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Tatyana@citylimits.org and Mariana@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.