While shelter staff are the primary schedulers of appointments at the city’s Asylum Application Help Center, a network of community-based organizations and legal providers can refer cases too. Yet city guidelines obtained by City Limits stipulate the groups can only refer migrants who are “within 4 weeks of their one-year filing deadline” for asylum.

Adi Talwar

The city’s Asylum Application Help Center is located at the American Red Cross Headquarters at 520 West 49th St. in Manhattan.Lea la versión en español aquí.

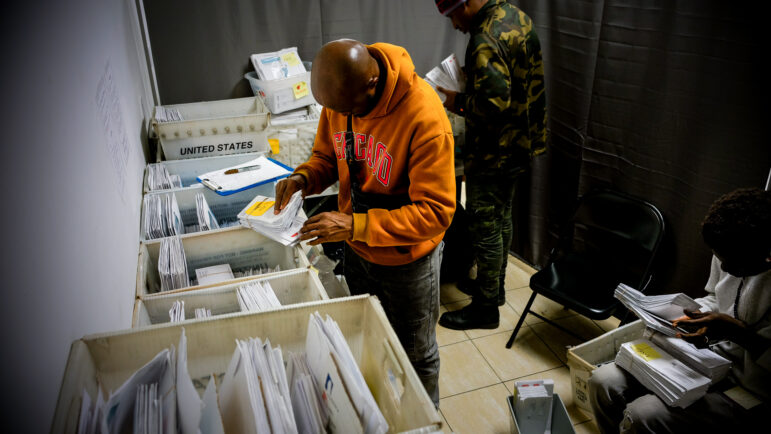

On a crisp morning in late August, migrants arrived at the city’s Asylum Application Help Center (AAHC) at the American Red Cross Greater New York headquarters, gathered at the side of the staircase, and waited to be called.

The staff would peek out the door and ask the next person who came in why they were there. The reasons for their visits varied: some sought to address simple queries, such as changing their address with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), or finding out when school would start.

For others, there was more at stake: they had appointments to apply for asylum, clutching folders of crucial documents under their arms.

Opened in 2023, the AAHC in Midtown Manhattan assists new immigrant New Yorkers in completing and filing applications for asylum, temporary protected status, and work authorization. It has helped file more than 67,000 such applications, Adams administration officials said last week, and earned a public service award from the American Bar Association in July.

“New York City has done more than any other locality across the country to manage the asylum seeker crisis, and a key part of that work is helping our newcomers take their next steps towards independence by helping them submit vital and complicated work authorization, TPS, and asylum applications,” Mayor Eric Adams said in a statement at the time.

But qualifying for an appointment with the AAHC is not so simple. Migrants must be in the shelter system or have recently left it, and must be eligible for work authorization, TPS, or asylum, City Hall explained.

While New York City shelter staff are the primary schedulers of asylum appointments at the help center, a network of community-based organizations (CBOs) and legal service providers that the city contracts with through various programs can also refer cases to the site.

“The City recognizes that community service providers may encounter eligible shelter/respite residents who’ve been unable to make appointments through their shelter case manager,” reads a set of guidelines from the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA), which oversees the help center. “To address this, the City will accept appointment referrals from nonprofit organizations contracted with the City.”

Yet those guidelines stipulate that these groups can only refer migrants who are “within 4 weeks of their one-year filing deadline,” reads a document outlining the rules, obtained by City Limits.

Under federal law, immigrants seeking asylum must file their application within one year of their most recent arrival in the United States. Submitting the form after the one-year mark could render them ineligible, according to USCIS, except under certain circumstances.

“DO NOT refer individuals who are more than 4 weeks from their Asylum One-Year Filing Deadline (OYFD),” reiterates instructions further down in the document.

Adi Talwar

The city’s Asylum Application Help Center in Manhattan.However, for CBOs that do not have a legal arm to assist the migrants they work with directly, this restriction has prevented them from making referrals for new arrivals, delaying all the economic advantages that come with filing for asylum: being able to apply for a work permit after 150 days, becoming self-sufficient more quickly, and qualifying for certain public programs.

“Many experience heightened stress and anxiety due to the uncertainty about their future and the constant fear of detention or deportation,” said Sophie Bah Kouyate, member and services manager at African Communities Together, one of several CBOs in the Asylum Seeker Legal Assistance Network, or ASLAN, a group of city-contracted providers assisting new immigrants with legal help.

“The inability to work legally forces some into low-paying, unstable jobs, which can lead to financial hardship and make it difficult to support themselves and their families. This situation also affects their mental health, leading to feelings of hopelessness and depression,” Bah Kouyate added.

In addition, applying for asylum can impact a migrant’s ability to access shelter in New York City.

Following a legal settlement reached this spring, the city has made it harder for adult migrants without children to extend their shelter stays past an initial 30 or 60 days, citing lack of space and resources. More than 64,000 migrants are in the city’s shelter system after more than 210,000 arrived in the city in the last two years.

Adi Talwar

The line outside the city’s “reticketing center” in the East Village in May, where newly arrived immigrants whose time limits in the shelter system have run out can make the case for more time.Having applied for asylum is one of the criteria that can earn someone another shelter stint, and as City Limits revealed last month, it can also mean getting a longer stay in a shelter—another 60 days instead of 30.

MOIA explained that the time-restricted referrals guideline applies to providers that are part of ASLAN, as well as the following initiatives: ActionNYC (a city-funded immigration legal support hotline), the Asylum Seeker Resource Navigation Centers (a network of CBOs serving across the five boroughs), the Haitian Response Initiative (a group of eight CBOs serving Haitian New Yorkers), NYC Small Business Services sites, and the NYC Department of Youth and Community Development’s sites for runaway and homeless youth.

“MOIA works with approved community-based partners—contracted under the city programs listed in the document—to ensure they are equipped to identify and refer eligible individuals to AAHC, when an individual has been unable to make an appointment through their shelter case manager,” MOIA Spokesperson Shaina Coronel said in a statement.

When asked why CBOs could only make referrals of individuals who were close to their first-year filing deadline, MOIA referred questions to City Hall, which in turn said that the CBO referral pathway is only one of many.

But CBOs who spoke with City Limits said the criteria leaves them with few options for clients seeking assistance if their filing deadline is more than four weeks in the future.

ASLAN members like the New York Legal Assistance Group, which provides legal services, said that when these newly arrived immigrants knock on their doors, they instead refer them to “pro se” workshops—less individualized help than one might get at the AAHC, but where applicants can fill out the paperwork themselves while supervised by organization staff.

In contrast, CBOs that don’t offer legal services and cannot make a referral to the AAHC must navigate the person’s need by telling them to return to the shelter they’re staying at, if they’re in one, and request an appointment there.

“The inability to secure an asylum appointment has profound consequences on the lives of migrants,” Bah Kouyate said. “Without access to these appointments, migrants are often left in a state of limbo, unable to obtain legal status or access essential services.”

City Hall did not provide data on how many referrals of cases within the four-week deadline have been made by the pool of organizations that contract with the city.

According to data shared by the supervisor of the ActionNYC hotline, Elizabeta Markuci, between June 2023 and June 2024, the program received over 50,000 calls on all types of immigration cases. It made 244 referrals to the AAHC during that time.

It referred another 2,900 callers to programs other than the AAHC, such as the immigrant court help desk of Catholic Charities, which provides immigration consultations and legal representation to migrants in New York City immigration court.

Markuci, director of hotline services, training and policy development in the immigrant and refugee services division of Catholic Charities Community Services, cautioned that the data does not give a clear picture of the city’s newly arrived population, or of how many migrants may have called who were not approaching their one year arrival deadline.

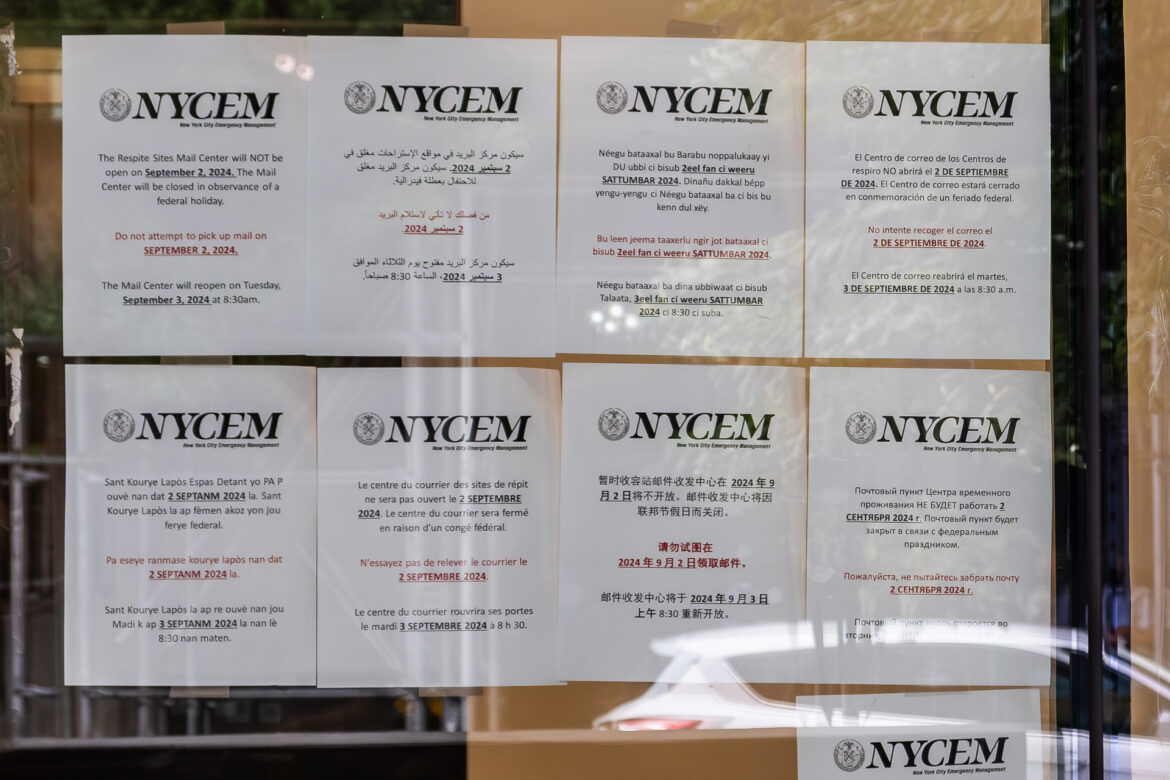

Adi Talwar

Signs regarding mail pickup on a window at the American Red Cross Headquarters, where the city’s Asylum Application Help Center is based.Outside AAHC that August morning, City Limits spoke with several migrants who managed to get appointments, and their stories varied. Some, like Colombian Andrea, who asked that her full name not be used for fear of jeopardizing her case, said it had not been easy and had taken several months.

“I spoke many times with the shelter’s staff,” she said in Spanish, referring to the large tent shelter for migrant adults at Randall’s Island where she’d been staying. “There are no people available, they told me, come another day.”

For Venezuelan Jesus Escalante, 38, receiving an appointment had taken less than a month. “As soon as I arrived, the people at the shelter in Queens helped me,” Escalante said.

Meanwhile, migrants who have been out of the shelter system for longer periods are not eligible for the services of the AAHC. They must either pay for an attorney themselves or seek out organizations that provide pro se services.

This was a point of contention for homeless advocates last month, after learning of the city’s plan to clear an encampment of migrants sleeping outside on Randall’s Island, including some whose shelter time limits had expired.

“Many clients have been forced to live outside because the shelter system has not offered them the help they need,” The Legal Aid Society and the Coalition for the Homeless said in a joint statement ahead of the city’s planned encampment sweep.

“While they could reenter shelter after completing an asylum application, the City has not offered them a means to access appointments at the Asylum Application Help Center, so clients are left with no safe shelter options,” the groups said.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Daniel@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.