Changes to the city’s funding formula for adult education programs have left some community organizations with decades of experience without contracts to continue their classes—for the time being. Six organizations that weren’t funded reported waiting lists with thousands of people.

Adi Talwar

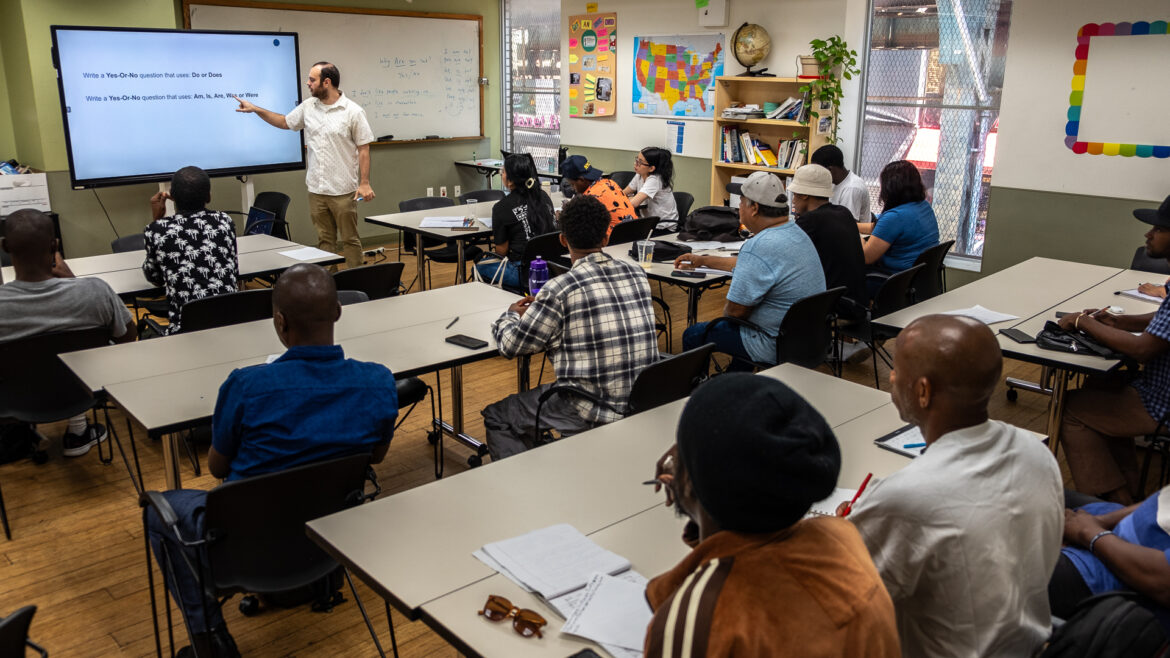

An English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) class at St. Nicks Alliance in Brooklyn. The organization is one of several offering adult education that saw its city funding dropped at the end of the most recent fiscal year in June.Lea la versión en español aquí.

Tiziana Perkins hopes to pass her last remaining science test in the next two weeks to earn a diploma through a High School Equivalency (HSE) program at St. Nicks Alliance, an organization that serves low- and moderate-income New Yorkers in Brooklyn.

“I’ll be graduating in August,” Perkins, 38, said smiling over a Zoom call. “As for the program, it helped me build more confidence; believing in myself and having a village that I was looking for for a long time.”

Perkins entered the HSE program in September 2023. She aims to become a phlebotomist and earn an associate’s degree in the medical field. “As far as me graduating, it helps with just motivating me to go beyond my limits, and knowing that I am capable of achieving what I want to accomplish as far as my goals,” she said.

For years, the city’s Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD) has worked with community-based organizations (CBOs) and educational institutions to develop an adult literacy system for New Yorkers over the age of 16, offering a range of literacy, English, math and other classes.

But even as the overall budget for these programs has grown in recent years, changes to how the city awards the funding has recently locked out many longtime providers, who say they’ve built relationships and trust with the communities they serve.

At least six organizations that previously offered these services saw their funding slashed with the start of the new fiscal year in July, forcing some to cancel programs and lay off staff. They include St. Nicks Alliance’s Adult Education program, which has since been running classes unfunded.

“Without this funding,” said Larry Rothchild, St. Nicks Alliance’s senior managing director of workforce development, “it puts the most marginalized community members at risk to achieve economic stability to get their high school equivalency and work towards employment and [a] career.”

In the last two fiscal years, the baseline budget for DYCD’s adult literacy programs was set at $11.8 million, funding that’s doled out to CBOs that bid on contracts through requests for proposals (RFPs). The last fiscal year that ended June 30 included additional funds for these programs, totaling $16 million.

After a struggle during this year’s budget negotiations, advocates and lawmakers secured $27 million—including a one-time $10 million infusion funded by City Council initiatives—for fiscal year 2025, which started July 1.

For this batch of funds, DYCD used a new formula for its RFP that focused on awarding organizations within “Neighborhood Tabulation Areas” (NTAs)—geographic communities with low English proficiency and educational attainment and high poverty rates, based on census data.

Under the new rules, CBOs inside of an NTA are prioritized, and only one organization within each NTA can win grant money. While providers say the new RFP language looks good on paper, in practice, they argue, it oversimplifies the complexities and nuances of adult literacy programs, which by definition serve economically disadvantaged people.

“The RFP’s over-emphasis on Neighborhood Tabulation Areas (NTAs) seems to have defunded high-performing agencies with full enrollment and waitlists of the target population while resulting in NTAs where no agency was awarded a contract at all,” said John Hunt, LaGuardia Community College’s assistant dean for pre-college academic programs, whose classes were among those impacted.

Moreover, providers argued that the new RFP did not take into account serving the needs of the thousands of migrants and asylum seekers who’ve arrived in the city since 2022.

DYCD did not respond directly to this criticism, but argued that the American Community Survey data the new formula is based on is “the most comprehensive nationwide survey currently available,” to account for how poverty and other indicators of need have changed in the last decade. Four out the 50 organizations awarded contracts so far are new providers, the agency said.

DYCD also previously defended the system as allowing it to expand its reach to more neighborhoods. “The Adams administration is committed to bringing equity to all New Yorkers,” DYCD Commissioner Keith Howard said in a statement at the end of June, “which is why DYCD developed a new RFP funding formula that incorporated poverty rates and expanded newly funded Adult Basic Education programs to communities such as East Harlem, Concourse Village, and Soundview.”

For the last several weeks, the city has been notifying CBOs if their project was selected in the NTA they applied for. Seven of 57 applicants are still awaiting a decision, said DYCD. A spokesperson could not say when all the designations will be completed, adding that the timeline for each RFP depends on a variety of factors and that the process follows set guidelines.

This delay in notification, though, is also delaying a $10 million-lifeline for programs that weren’t selected in the form of discretionary funding from the City Council, which is looking to help plug the gap, according to a spokesperson for Speaker Adrienne Adams.

It’s not clear how many others have been turned down for the funding, though six providers of programs that weren’t selected told City Limits they had waiting lists with hundreds of people, totaling more than two thousand prospective students.

Since funding for the prior fiscal year ended in June, these organizations are currently at a crossroads, weighing whether to close their adult education programs altogether or stretch a few dollars to continue providing the service, knowing it is not sustainable in the long term.

Johan Lopez, director of adult and immigrant services at Sunnyside Community Services in Queens, explained that not being selected for the NTA decimated its programs, which were 98 percent funded by DYCD. The organization was forced to let go of four full-time staff and nine instructors.

“We had 39 classes,” in fiscal year 2024, Lopez said in an interview over Zoom. “This year, as our funding stands, we’ll be able to offer three classes.”

Sunnyside’s Associate Executive Director Monica Guzman said they’ve reached out to private donors to help make up for some of the lost funds. They also hope to secure some of the additional $10 million secured by the City Council.

“It’s gonna take a long time to build this program back, we really are waiting to hear what the City Council is going to do with that $10 million,” Guzman said over Zoom.

The Center for Immigrant Education and Training at LaGuardia Community College, which provides adult literacy classes, lost all of its DYCD funding as well on July 1, representing a loss of 145 seats.

Adi Talwar

An English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) class at St. Nicks Alliance in Brooklyn on Aug. 5, 2024.“Some of those students expected to be returning to campus in the fall to continue progressing through our low-intermediate ESOL [English for Speakers of Other Languages] levels, so their educational pathways are being interrupted,” explained Hunt.

Mercy Center is another organization that saw its budget obliterated, with 38 classes offered last fiscal year—and around 2,150 registered ESOL students—to only three this fiscal year, for barely 200 students.

So far, the Mercy Center has laid off 10 staff members from the ESOL program and expects to lay off more if funding isn’t restored, said Judit Criado Fiuza, the director of adult education, immigration, and workforce development. Agudath Israel of America, another provider based in lower Manhattan, advised its teachers to apply for unemployment benefits while stopping all classes until further notice.

Anna Kaganova, senior grants manager at Center for Family Life, said her organization is half a block away from the NTA in Sunset Park, but received notification that they didn’t make the cut.

“We have not yet heard from DYCD about why we were not selected for the program,” Kaganova said. “But just the one contract award per NTA feels like a restrictive model.”

“We serve a lot of people from the NTA we applied for, but we’re not directly located in it,” she added. “But then we also serve a lot of people outside of that NTA in the broader sense of our community.”

The funding snafus come as providers of these programs have seen increased demand for classes, especially after more than 210,000 new immigrants arrived in the city in the last two years, 64,300 of whom remain in its shelter system.

Jude Pierre, program manager for CAMBA’s Adult Literacy Center, explained that they had to close enrollment for English classes from winter 2023 to spring 2024 after hitting capacity, having received more than 100 applications per day.

“We temporarily reopened registration for English classes just before this summer,” Pierre wrote in an email, saying they have a waiting list of nearly a thousand people. “Since we don’t have as many classes as before, we got overwhelmed quite quickly and had to stop registration again.”

“We have seen a significant increase over the last year in newly arrived English language learners seeking ESOL services on campus,” Hunt, at LaGuardia, explained. “Many of those applicants are newly-arrived in the city and in need of basic level adult literacy services; all are low-income New Yorkers who speak only basic English, if at all.”

Without additional funds, Hunt said, applicants to LaGuardia’s ESOL program will remain on the waitlist for over a year. He emphasized that those who cannot access ESOL or GED classes face greater barriers to civic participation, engagement in their children’s education, access to post-secondary education, and workforce training pathways.

“In fiscal year 2024 we registered over 2,000 students, all low-income immigrants, 75 percent of which had critical housing issues,” explained Mercy’s Criado Fiuza. “Demand was such that we could have registered double the number of students if we had the funds and the space.”

Still, providers are hoping the extra funds from the Council will allow them to bring their adult programs back to life.

“Thanks to this additional $10 million,” Pierre said, “more English classes may be offered throughout the city as of the fall. We hope CAMBA is among the service providers considered for funding.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Daniel@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.