According to the New York State Board of Elections, 329 candidates registered for the first state-level public campaign finance program, which aims to curb the influence of big money in politics by matching small, local donations with public funds.

Adi Talwar

Jonathan Soto, a candidate running for Assembly, at a campaign fundraiser in the Bronx on May 6. He’s among more than 300 candidates running for election this year who registered for the state’s first public matching funds program.The last time he ran for office in 2022, Jonathan Soto’s time and energy was focused on big dollar donors. The East Bronx candidate was up against Democrat Michael Benedetto, who has held onto his title as District 82 assemblymember for nearly 20 years.

Soto ultimately lost that election to Benedetto, who amassed significantly more than his challenger in campaign contributions in the lead up to the June 2022 primary, records show. This time around, Soto—who is running once again for the same Bronx Assembly seat—is hoping a new fundraising law that’s already boosted his campaign’s war chest by $43,049 will help level the playing field.

Enacted by the governor and State Legislature in 2020, New York’s Public Campaign Finance program allows candidates running for state office to qualify for matching funds for contributions between $5 to $250 made by in-district donors.

This year’s elections—during which State Assembly and Senate seats are up for grabs—is the first time candidates for those offices will be able to take part. During the next election cycle in 2026, those running for governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and state comptroller will also be able take advantage of matching funds if they qualify and choose to opt in.

The goal of public financing is to curb the influence of big money in politics by amplifying the impact of small, local donors, which has dwindled since the 2010 Supreme Court decision Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which allowed corporations and other outside groups to funnel large amounts of money towards elections.

The program can also offer a boost to challengers who lack the financial backing or donor network to run a competitive race against an incumbent—especially in New York, where there are no term limits for state legislative offices. That means some State Assembly and State Senate incumbents remain in office for years or decades at a time, earning name recognition that’s hard for a newcomer to match.

Elections also cost a lot of money. People with flexible schedules that allow them time to campaign, as well as those with existing wealth and resources, automatically have a leg up, explained Sarah Bryner, director of research and strategy for the good government group OpenSecret.

“Those factors come together and make it harder for people in our private-funded election system to get what they need to be successful at the ballot box,” said Bryner.

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, at least 14 other states and 26 localities use some form of public campaign financing. New York City has a program for candidates running for mayor, City Council, and comptroller that dates back to 1988.

While New York State is the latest to join the ranks, it takes the cake in terms of its scope, says Joanna Zdanys, senior counsel in the Brennan Center’s Elections & Government Program.

“It is the strongest campaign finance reform we’ve seen enacted since Citizens United to respond to the overwhelming influence of wealth in our politics,” she said.

How does it work?

As election season heats up—the primary takes place June 25, and the general election Nov. 5—so too will candidates’ fundraising efforts, including distributions of the state’s matching funds, the first round of which went out earlier this month.

Each time someone donates between $5 to $250, the state uses a formula to match the contribution with taxpayer money. For example, a $50 donation—which is matched 12 to 1—becomes $600. After the first $50, the match rate is 9-1 for the next $100, and 8-1 for the next $100 after that. In this way, candidates get a bigger bang for each donor buck.

“People can proudly come with your $5 or $10, because they know it’s going to multiply,” said Assemblywoman Stefani Zinerman, who represents District 56 in Crown Heights and Bed-Stuy and is campaigning to keep her seat this year.

To unlock matching funds, State Assembly candidates have to raise $6,000 from 75 in-district residents, while State Senate candidates have to raise $12,000 from 150 in-district residents. The thresholds are different from statewide races for governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and comptroller, which have their own matching formula. Only in-district donations are matched, although candidates are still permitted to seek donations outside of their district if they choose.

If they meet all of the requirements, candidates will see matching funds hit their committee’s bank account at various points in the election cycle. They can put this money towards campaign expenses like social media and cable ads, field operations, office costs, and staff wages.

“These are things that cost a lot of money. And in a presidential year, they cost even more,” said Chris McCreight, a matching funds participant who is running against incumbent Republican Assemblymember Alec Brook-Krasny in South Brooklyn’s District 46.

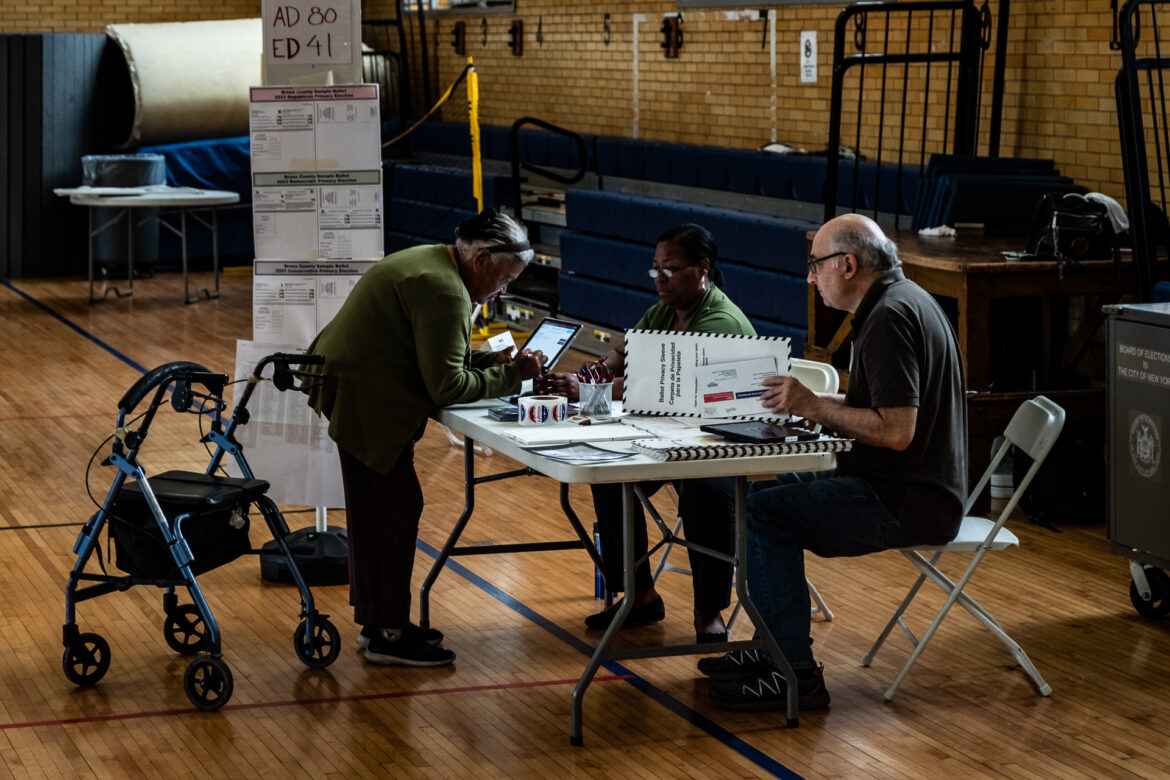

Adi Talwar

A polling site in The Bronx during the 2022 primary.Who’s taking part?

According to the New York State Board of Elections, 329 candidates registered for the program before the Feb. 26 cut off.

The first payout date for the primary was May 13, when 35 participating Senate and Assembly candidates received matching funds totaling just under $3.6 million, according to a report from the Public Campaign Finance Board. The second round of payouts, approved on May 22, will dole out a collective $2.3 million to 50 candidates this week, records show. The first payout date for those running in the general election will be July 8.

The sign up numbers are impressive for an initiative that’s still finding its footing, according to Zdanys—especially compared to other prominent matching fund programs across the United States.

“The rate of participation in this program this year far outpaces what we usually see in the first run of a public campaign financing program,” she said.

The Brennan Center is hopeful that the state-wide initiative will be able to replicate the benefits of the city’s matching program, particularly when it comes to equitable access. According to one of the Center’s reports, the public matching funds program was partially responsible for ushering in the city’s most diverse City Council to date in 2021 (the city increased the amount of its matching payouts via voter referendum in 2018).

The state program has drawn support from a diverse cross section of candidates on both sides of the political spectrum, proponents say. Roughly three-fourths of legislative districts were represented among those who registered for it, according to the Brennan Center, including 79 percent of Assembly districts and 86 percent of Senate districts.

Participants include 127 incumbents (including Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli), roughly 40 percent of whom identify as Republican, the Center found. The remaining 202 were presumably challengers in the primary election or candidates running for open seats.

“We think that speaks to…a widespread desire for candidates to have ordinary people help run their campaigns,” said Tom Speaker, legislative director for Reinvent Albany, another group that has been a strong advocate for matching funds.

Even Senator James Skoufis, a Democrat representing District 42 in the Hudson Valley who introduced legislation to reform the program, is among those who signed up for it. He figured that opting out would only disadvantage him in the end.

“Regardless of whatever concerns and criticisms I have, I’d be shooting myself in the foot to not do it,” he said.

For people like McCreight, who is vying to unseat an incumbent in November, the matching funds have given him more skin in the game. “I couldn’t run in this race if there weren’t matching funds,” he said. “My ability to raise is really contingent on having support in the district.”

Beyond diversifying the field of candidates and nominees, supporters see the program as a way to bring more voters into the fold, given that they can now see their donations amplified.

“We’ve been cultivating a lot of new donors in the district who’ve never donated before,” said Soto, the East Bronx Assembly candidate.

He was approved for another $9,251 in matching funds last week—on top of the more than $40,000 he received in the first distribution earlier in May—while incumbent Benedetto was approved for $89,700 so far, records show.

Adi Talwar

A voter prepares to cast a ballot in 2023.What are opponents saying?

While the Public Campaign Finance Program is just kicking off, it’s already had its share of challenges. Last June, Democratic lawmakers introduced a bill that would have dramatically changed the rules of the game. While it passed in both chambers, Gov. Kathy Hochul vetoed it.

But it didn’t stay dormant for long. In early April, Sen. Skoufis resurrected the bill. But he made it more “palatable” this time by eliminating the most controversial provision, which would have raised the donation amounts eligible for a match, allowing the first $250 of contributions as large as $18,000 to be boosted by public funds, which critics say conflicts with the intent of the program.

Skoufis’ current version is aimed at increasing the number of donors and amount of money a candidate for state office would need to raise to be eligible to receive matching funds. This more scrupulous requirement would provide proof of a candidate’s credibility and viability before they can unlock public money, he told City Limits.

“One should not be able to snap their finger and have taxpayer dollars fall out of the sky and into their campaign accounts,” he said.

Beyond legislative challenges, there are critics of the program who worry it could be abused by bad actors. The alleged straw donor scheme tied to Mayor Eric Adams’ 2021 run for office put a spotlight on the potential pitfalls of the city’s matching funds, and critics argue that without proper oversight, candidates and donors alike can exploit the system.

In April, The CITY reported on how the state program lacks a spending cap—unlike the city’s version, which prohibits participating councilmembers from spending more than $182,000 in an election year, to “ensure money will not decide an election between participating candidates,” according to the NYC Campaign Finance Board’s website.

Despite having what he called “significant momentum” during an April interview, Skoufis’ bill, which has 20 sponsors, wasn’t included in the state budget that passed in April, as the senator had hoped. Opponents who spoke with City Limits voiced concerns that changing the rules with the election cycle underway would have been disruptive and unfair.

The budget did include money to continue the public campaign finance program—$100 million for matching funds and $14.5 million for administrative costs—an inclusion celebrated by local good government groups.

“We think it’s going to make it so that campaigns will get a lot more of their donations from everyday people and less from those with bigger pockets, which we think will have a really positive impact on the kind of policy outcomes that we see in New York State,” said Speaker from Reinvent Albany.

This story was produced as part of the 2024 Elections Reporting Mentorship, organized by the Center for Community Media and funded by the NYC Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment.

To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.