A Crown Heights building in limbo could inspire more landlords to deregulate through demolition—or more tenants to fight to stay in their homes.

Adi Talwar

Alema Finnigan, Pamela Hicken and Rosalee Frater stand outside the entrance of 285 Eastern Parkway in March 2024.Rosalee Frater understands the economic forces she’s up against. The things she loves about her neighborhood, that the 61-year-old mother of five has known since she was a teenager, have helped solidify its status today as what she calls a “pot of gold.”

Frater’s rent stabilized apartment at 285 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights is half a block from the subway. The Brooklyn Museum and stately Central Library are a few blocks west, and she can easily walk to Prospect Park.

So when she and her family started receiving buyout offers from their landlord Renaissance Realty Group in late 2019, they declined. Frater’s mother Alema Finnigan, who lives downstairs, also refused to leave, as did two other senior women, Pamela Hicken and Jean Thompson. At the time, they had all been neighbors for over 40 years.

Today, their four-story building is nearly empty. Thompson moved out abruptly in January, leaving just three apartments rented. But by standing their ground, the remaining tenants are delaying their landlord’s application to knock the building down, along with adjoining 291 Eastern Parkway—a combined 33 apartments.

Renaissance has filed plans for an eight-story building on the site, with 76 units, a healthcare facility, and 40-car garage. They claim this would be a net gain for the neighborhood in the midst of an historic housing shortage. But pursuing demolition is also one of the few legal pathways to remove an entire building from rent regulation.

Now this familiar story—a tenant’s home is a landlord’s financial asset—has a new character. In 2015 Renaissance took out a $5.5 million mortgage from Signature Bank. After the bank collapsed spectacularly in 2023, the loan passed to a federally-backed joint venture with a mission to preserve affordable housing.

Homes and Community Renewal (HCR), the state agency that oversees regulated housing, has yet to say if Renaissance can proceed with evicting the remaining tenants at 285 Eastern Parkway, a prerequisite to demolition. If, or how, the new lender will exert pressure isn’t yet clear.

But Frater’s plan is. “My thing is stand firm, hold your ground, because that’s where you live at,” she told City Limits on a warm evening in October. “And if you don’t fight for you, who’s going to fight for you? No one. You got to stand up to the end.”

How to deregulate a building

Rent stabilization has allowed Frater and her neighbors to live affordably for decades, as their neighborhood has changed dramatically. Crown Heights North saw its Black population drop 20 percent over the decade ending in 2020, from a majority to a plurality, while its white population nearly doubled. Rents have soared.

The neighborhood’s median asking rent was $3,000 in February, according to Streeteasy. The holdout 285 Eastern Parkway tenants, by contrast, pay between $516 and $810 a month, thanks to limited allowable rent increases. But even their own building has been in a state of transformation for years.

Before the 2019 passage of the state’s Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act (HSTPA), landlords could remove apartments from stabilization by churning through tenants. Vacancies came with a tantalizing 20 percent rent boost. By renovating, sometimes fudging the math, landlords could push them even higher.

Exactly when, and how, Renaissance deregulated most of 285 and 291 Eastern Parkway isn’t clear. In April 2022, tenants found a listing for one apartment touting a “Gorgeous NEW Kitchen.” Other empty units appear fresh and clean, even as issues in the occupied ones, like sagging floors and damaged ceilings, go unfixed.

But the building also underwent major renovations years ago. Lashawn Diallo, one of Frater’s daughters, recalls some tenants taking buyouts in the late aughts. The city approved renovation plans for 291 Eastern Parkway starting in 2006, and over half of 285 a few years later. A 2013 sales pitch called the property 75 percent “free market.”

Adi Talwar

Rosalee Frater in her apartment at 285 Eastern Parkway in early October 2023.By December 2019, when Renaissance agent Michael Schultz approached Frater and her husband with an initial $149,000 offer, stabilized tenants remained in just seven of the apartments on her side of the building. Two accepted buyouts by June 2022, and another tried to take over her late grandmother’s lease, only to be evicted last summer.

The trajectory on the other side of the building is more hazy, but Renaissance described it as entirely vacant in an October 2022 ledger. A few people appear to be living there today, though Frater, Hicken and Finnigan believe they are affiliated with the landlord.

Diallo, who is currently living in her parents’ apartment with her teenage daughter, believes that Renaissance never anticipated that a few tenants would refuse to move. “That was a wildcard,” she said.

Hicken says she had a clarifying experience in early 2021 when Schultz, of Renaissance, asked her to encourage others to take the money and leave.

“They probably figured with my mouth and my pull, I could talk to the other tenants,” she recalled. But she refused what she saw as a betrayal to her friends. Instead, she called local Assemblymember Phara Souffrant Forrest, who was a member of the Crown Heights Tenant Union before taking office.

Forrest says that she sees her role as helping tenants organize, as “that’s the source of our power.” Her staff began hosting meetings on the 285 side of the building in May 2021, with a mix of old-timers and newer tenants, even as it was emptying out. The latter, living in unregulated apartments, didn’t have any rights to a lease renewal.

The demolition factor

Today, demolition is one of the only ways to definitively wipe out a building’s regulated status. The 2019 rent laws narrowed the path for co-op and condominium conversion, and increased scrutiny on the “substantial rehabilitation” route, which requires replacing most of a building’s systems.

The New York City Department of Buildings issued eight demolition permits for buildings with stabilized apartments in 2023, a City Limits analysis found. Last year’s permits cover about 400 units, according to counts from Department of Finance tax bills—the most since the passage of the HSTPA, though still trailing the early 2010s.

But the process is complicated. Before bringing in a wrecking ball, a landlord must get permission from HCR to deny renewal leases to any regulated tenants in the building. If granted, tenants are owed sizable payments, which are calculated using a formula and were recently increased to keep pace with market rents.

“We generally tell a client it’s three to five years,” said Deborah Riegel of the law firm Rosenberg & Estis, who is not involved in the Eastern Parkway application. “Time is death in development. Things need to move and demos don’t move quickly.”

Renaissance filed its request in July 2023. The few remaining tenants immediately opposed it with an assist from Brooklyn Legal Services, saying demolition would violate a term in the building’s mortgage and could even be a bluff, given the apparently good condition of the empty apartments.

The tenants also accused their landlord of lowballing the concession payments HCR requires, in a ploy to make upfront buyouts look more attractive and lure them out faster.

At 73, Hicken has no interest in leaving the apartment she’s called home since the late 1970s, and which she shares with her adult son. Sitting in her living room in November, she recalled the years that she’d hear gunshots throughout the night: “boop, boop, boop.” Today, the neighborhood feels safe.

Adi Talwar

Pamela Hicken in her living room at 285 Eastern Parkway in November 2023.Hicken hopes to retire soon, but for now still works for Mount Sinai Hospital System. Her work computer is nestled among trophies from Star of Bethlehem, part of Enoch Grand Lodge in Bed-Stuy, where she’s associate matron. A stuffed tiger from her daughter surveys from the couch. “Look at my age,” she told City Limits. “Where am I going?”

Parker Winship, one of the attorneys assisting Hicken and her neighbors, believes Renaissance’s application shouldn’t be considered in isolation. The state legislature is currently debating modifications to the 2019 rent laws that could help landlords increase rents on an apartment-by-apartment basis.

But when it comes to building-wide deregulation, Winship sees Eastern Parkway as a bellwether, particularly for landlords in expensive neighborhoods like Crown Heights—it could inform whether they “decide to pursue demolition in the future.”

Enter the FDIC

When Renaissance took out the $5.5 million mortgage on 285-291 Eastern Parkway from Signature Bank in 2015, low interest rates meant that landlords could get cheap financing for large amounts of debt, based on high building valuations that were only expected to keep growing.

“In 2015 it was hard to imagine anything ever going wrong in New York City real estate for landlords and investors,” said Jacob Udell, director of research and data at University Neighborhood Housing Program (UNHP), an affordable housing developer.

But as early as 2018, according to Udell, they began to suspect a peak. Then the HSTPA narrowed landlords’ ability to raise rents and deregulate apartments. Rent collection fell during the COVID-19 pandemic and inflation and interest rates rose—all factors that could leave a building with more debt than value. Then Signature collapsed.

In a post-mortem, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) concluded that the bank had underestimated risks in the volatile crypto currency industry. But real estate was always a big part of its business. When it failed, Signature’s $33 billion commercial real estate portfolio, mostly multifamily properties, passed to the federal government.

In December, the FDIC appointed a joint venture led by the Community Preservation Corporation (CPC), a nonprofit housing finance company, to service $5.8 billion of that pool, in which it has a 5 percent stake. The debt is secured by about 35,000 New York City apartments, largely regulated, including those at 285-291 Eastern Parkway.

Adi Talwar

The exterior of 285 Eastern Parkway in November 2023.Renaissance’s lawyer, Joseph Goldsmith of Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens, has argued to HCR that a no-demolition clause in the mortgage is irrelevant because the debt came due in October of last year.

But CPC confirmed to City Limits that the FDIC* granted Renaissance an extension that month. Records reviewed by City Limits show the mortgage is not due to be fully paid off until the end of January 2026, and that the entire $5.5 million principal is still outstanding.

In a case like this, where a building secures a loan, demolition is not allowed until the debt is paid, a spokesperson for CPC said. The FDIC has also established rules for its joint ventures to “facilitate the financial and physical preservation of underlying collateral,” and has a statutory obligation to preserve affordable housing.

The feds’ newly released operating agreements are dense and partly redacted. But it’s clear that they include a nearly $580 million fund to help the CPC-led venture fix former Signature buildings, and flexibility for CPC, which is compensated largely through management fees, to modify loans.

UNHP and the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD), a member organization of nonprofit developers and tenant groups, have been in talks with the FDIC and CPC over the last year. Eventually, they’d like the new lender to test more interventionist strategies, like transferring buildings to more responsible owners.

“In New York City especially, housing is seen as for profit, but we actually have a moment where we can switch the narrative and think of housing as a human right,” said Will Depoo, senior campaign organizer with ANHD.

Renaissance owes up to $45 million in former Signature loans across eight buildings, according to an UNHP* analysis of public data, suggesting broader leverage.

Not all Signature buildings are alike, cautioned Ben Carlos Thypin, a broker who has worked on transactions involving properties with a mix of apartments similar to 285-291 Eastern Parkway. Not only is the property in a very attractive location, but it’s largely deregulated, he argued, suggesting it’s still more valuable than the mortgage.

Renaissance could simply pay its debt to shrug off any pressure from CPC, he predicted. And demolition could be a tantalizing incentive to do so. A nearby parcel in Prospect Heights recently listed for $297 per buildable square foot. Napkin math suggests the Eastern Parkway land could be worth over $15 million.

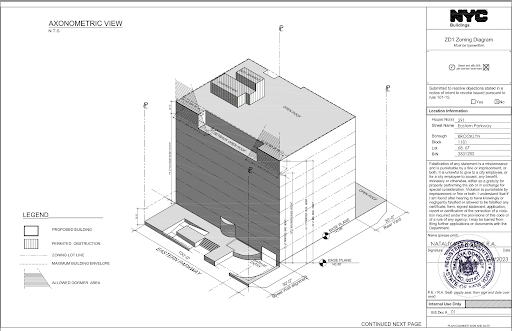

NYC Dept. of Buildings

Rendering of Renaissance's proposed replacement building for 285-291 Eastern Parkway.“Most of the buildings that secure mortgages taken over by CPC are not in this situation,” Thypin said, adding that the venture should “focus its efforts and capital on pursuing preservation outcomes in those situations in which they have more leverage.”

Adding another wrinkle, the state may soon negotiate a new residential tax incentive. Local zoning would not require Renaissance to build any affordable apartments on the Eastern Parkway lot. But, left to its own devices, the developer could be tempted to build more regulated and low-income apartments than currently exist there.

Frater’s daughter Diallo would rather see the existing, empty units re-regulated and rented affordably. “There’s so many people in shelters, and just living on the streets,” she told City Limits. “Fill the apartments!”

This kind of intervention may hinge on the availability of government subsidies, said Samuel Stein, senior policy analyst at the Community Service Society of New York (a City Limits funder). But in this sea of unknowns, he urged CPC to explore its leverage rather than “hope for the best from a private landlord.”

Will they, won’t they?

It is difficult for Hicken, Frater and Finnigan to picture their building, with its brick facade and Greek columns, reduced to dust and rubble. To them, the empty apartments seem habitable.

In early 2021, before pursuing demolition, Renaissance put the building up for sale. A promotional video from the time, with a clubby soundtrack, describes it as recently renovated with air rights.

“People could move in tomorrow,” said Michael Hollingsworth, a former City Council candidate who is working with the tenants as an organizer with the Crown Heights Tenant Union. “So the idea that the building needs to be knocked down, it just doesn’t make sense.”

Historically, it wasn’t unheard of for landlords to start pursuing demolition, enter negotiations with tenants, and then modify their plans once they settled on buyouts, according to Riegel, the attorney with Rosenberg & Estis.

“There were for sure owners that, once they got through negotiations with the tenants, had more freedom to not take the entire building down to the foundation,” she said. But HCR now requires landlords to submit approved demolition plans, she added, which are costly and time-consuming and effectively eliminate that flexibility.

Renaissance did not respond to detailed questions about its plans for the property, or actions to date. But in a recent letter to HCR, it accused the remaining tenants of “comparing apples to oranges,” and said past renovations don’t rule out “more economically advantageous” demolition.

Setting aside predictions about the landlord’s ultimate course, the tenants say it's time for action, and that HCR—which declined to discuss any pending case with City Limits—should at least be talking to Renaissance’s new lender, as they have sought to.

In November, Frater, her mother and Diallo were able to sit down with FDIC staffers to discuss the situation in their building. The location was somewhat surreal: Signature’s recently-emptied Manhattan offices. Hollingsworth accompanied them. “We were in the boardroom where I guess a lot of the, you know, devious deals were done,” he recalled.

Such meetings with tenants are crucial if the ultimate goal is to fix apartments and prevent displacement, said Depoo of ANHD.

But while it was exciting, the ladies are still waiting for a follow up. And CPC’s response to a recent request for a sit-down was troubling. The lender declined to meet unless the landlord is also present, later telling City Limits that excluding Renaissance could create legal liability and a perception of interference with the owner’s operations.

CPC said it’s willing to talk to Crown Heights Tenant Union organizers as a sort of intermediary to learn about building conditions and Renaissance’s actions, but Hollingsworth was not impressed.

“People really thought it was going to be a shift in the way we deal with the landlord-tenant dynamic,” he said. “We thought that leverage could be used to help the tenants. If that doesn’t come to fruition it’s going to be pretty disappointing.”

Formidable foes

In February, Renaissance offered fresh buyouts to Frater and Finnigan, upping the ante to $285,000 and $315,000, respectively.

Brooklyn Legal Services believes these latest offers aren’t much larger than what they would ultimately be owed if the demolition application prevails. The new HCR rules also clarify that the agency can withdraw its approval if it finds, after the fact, that a landlord was acting in bad faith.

But the ongoing pressure has been unnerving. “How can I sleep at night?” Finnigan wondered in March, gathered with her neighbors in the quiet lobby of their building.

In his latest letter to the state, Goldsmith, Renaissance’s lawyer, argued that the women are standing in the way of “a newer, more modernized, and safer building” and engaging in “exactly the conduct” that contributes to New York City’s housing shortage.

Chris Janaro

Hicken takes the bullhorn at a rally outside of 285 Eastern Parkway on March 9, with an assist from Michael Hollingsworth of the Crown Heights Tenant Union.That logic seems to have fallen flat with City Councilmember Crystal Hudson, who said she is planning to write to HCR opposing his client’s application. And while the developer’s proposed replacement building wouldn’t require her sign-off, she warned Renaissance could end up on her list of bad actors “who we shouldn’t be working with.”

“Anybody who is trying to deregulate units and certainly displace older Black women who have been there for decades—for sure, that’s a problem,” Hudson told City Limits.

But if at any point Hicken, Frater and Finnigan change their minds and take the money, the HCR application will no longer be necessary. Renaissance might still have its new lender to contend with, but its most formidable foes would be out of the way. For the ladies and their families, the preservation fight would be lost.

At a drizzly March 9 rally outside the building, alongside other Brooklyn tenants facing deregulation attempts in their buildings, Hicken kept her remarks brief. “We would be lost without our apartments,” she shouted into a bullhorn.

“You know grandmothers know how to fight,” she added. “And we fight to win!”

Data analysis by Patrick Spauster. Additional reporting by Chris Janaro.

*An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that CPC granted Renaissance's mortgage extension, when in fact the FDIC did so. UNHP, not ANHD, performed the debt analysis referenced. City Limits regrets the errors.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Emma@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

2 thoughts on “Staring Down the Wrecking Ball, These Brooklyn Grandmothers Won’t Be Moved”

This is disappointing on multiple levels. It is morally rotten for the owners to forcibly displace these women so they can deregulate and demolish the building. Beyond that, demolishing existing buildings is terrible for the environment (reusing and repurposing existing structures is always the greenest option) and has nothing to do with a benevolent desire to create more housing and everything to do with wanting to fatten their wallets. This city’s addiction to tearing everything down so real estate investors can build bigger, uglier buildings is a total shame.

Why wasn’t this building landmarked? Doesn’t Crown Heights have an extensive landmark district?