While Mobilization for Justice’s staff union has particular grievances—they say their employer has failed to stay competitive with its peers—many members are experiencing a strain familiar to tenant lawyers citywide.

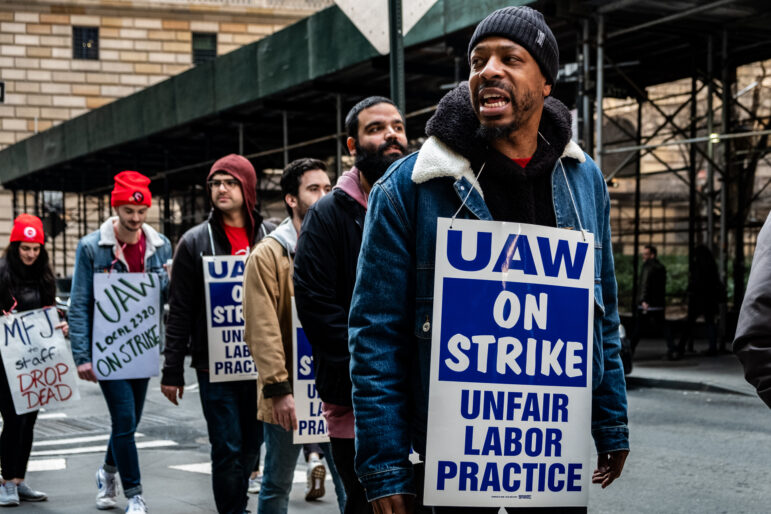

Adi Talwar

Dorien Brown picketing with his colleagues outside Mobilization for Justice’s Manhattan office on Tuesday, Feb. 27.When a tenant calls the nonprofit legal services provider Mobilization for Justice (MFJ), or walks into the organization’s Manhattan office, the first person they speak to could be Dorien Brown, an executive secretary and member of MFJ’s support staff.

“I just make sure that the first interaction is pleasant,” Brown told City Limits Tuesday, before joining more than 80 colleagues and supporters on the picket line outside MFJ’s 100 William St. headquarters. “I’m understanding. Sometimes I’m listening for 30 minutes to an hour.”

Brown and his 110 unionized coworkers, of the Legal Services Staff Association (LSSA) Local 2320, went on strike Friday, after 93 percent of voting members opted to reject a contract offer they say falls short of their demands, including fair pay and healthcare benefits and more flexibility for remote work.

One of the union’s priorities is higher compensation for non-attorneys like Brown, who they say are primarily people of color. Support staff salaries under the last contract started at about $51,000, while paralegals started around $53,000.

The rejected offer would shift support staff up to the paralegal scale and see salaries increase 15 to 20 percent by the end of 2026 for non-lawyers with four or fewer years on the job. Those with longer tenure would see smaller raises.

Management also proposed a $2,750 bonus for non-lawyers who help with translation, and a $3,000 bonus for support staff to work in the office four days a week, rather than three—a move the union said cuts against their demand for equal flexibility for all to work remotely.

The offer moves the lowest paid staff to a pay scale that is still inadequate, the union added, and only builds on the existing salary steps by 2 percent each year.

“If that doesn’t keep up with inflation, which it hasn’t been, then the value of those steps declines and degrades over time,” said Brenden Ross, a member of the union’s bargaining team and senior staff attorney with MFJ’s Mental Health Law Project.

While the union has particular grievances for MFJ—they say the organization has failed to stay competitive with its peers—many members are experiencing a strain familiar to tenant lawyers citywide. On the frontline of fighting evictions, they are seeing firsthand how the city’s Right to Counsel program is failing to keep up with demand.

In addition to housing, MFJ’s practice areas include foreclosure, bankruptcy, immigration, government benefits and disability rights.

Passed into law in 2017, Right to Counsel was billed as a first-in-the-nation program providing “universal access” to housing court attorneys for those eligible. But it has never been funded to serve all who qualify, despite a citywide expansion in 2020.

In light of this, Brown has had to tailor his messaging to low-income tenants who realistically won’t be matched with a lawyer right away, assuring them that their landlord cannot kick them out without going through a court process. These clients are struggling to stay housed and he’s trying to help them. Both are struggling to pay their bills.

“It’s like we’re both in the same boat, right?” he said.

This week’s strike launch also comes as MFJ and other legal nonprofits wait anxiously to find out how the city plans to divvy up $408.5 million in Right to Counsel funding for the next three years—an amount Mayor Eric Adams’ administration estimates will cover about 44,000 cases annually.

Adi Talwar

MFJ union members say the stress of the job, combined with noncompetitive salaries, has led to attrition.The organizations—including the Legal Aid Society and Legal Services NYC, another LSSA shop—said last year that they would need $461 million annually to represent an estimated 71,4000 qualifying households. They have yet to update their estimate for 2024, but maintain that the city’s planned allocation is grossly inadequate.

Under MFJ’s offer, attorney salaries start at $76,000 for law graduates before they pass the bar exam and max out at about $136,000 for the longest-serving. Legal Aid, whose union ratified a new contract in December, starts law graduates at about $80,600 and includes more salary steps, reaching north of $140,000.

Similar to MFJ’s offer for non-lawyers, its proposal for attorneys includes raises upwards of 20 percent over three years for the newest employees, and as low as 6 percent for the most senior, building on the existing salary steps by 2 percent per year.

In a press release, MFJ Executive Director Tiffany Liston said the organization sought to “achieve better pay parity,” account for inflation, and put compensation “near the top end of legal services organizations.”

“We encourage the union to reconsider the generosity of MFJ’s offer, especially in light of the organization’s current fiscal realities,” Liston added. “Our many clients need us and a prolonged strike will not benefit them.”

Over email, MFJ Chief Development Officer Eric Alterman said that the lack of clarity on city funding for tenant lawyers has impacted the organization’s ability to budget. “We are indeed underfunded, as we and just about every other legal services organization keep pointing out, resulting in the operating deficit we have to sustain,” he said.

Meanwhile, MFJ union members say the stress of the job, combined with noncompetitive salaries, has led to attrition.

Larger raises for newer staff reflect MFJ’s interest in attracting less-experienced attorneys, according to the union, but comparable raises for longer-term employees would help retain them over time.

According to management, 28 staff members resigned in 2023 across all practice areas. The organization has 42 staff attorneys in the housing practice, which took on over 3,000 eviction cases last year, and another starting in April. Eight law school graduates are slated to join in September, but MFJ still has 12 housing lawyer vacancies to fill.

Shirin Dhanani, a staff attorney in the Bronx housing practice, said that attrition has made her job more challenging. As colleagues depart, she must take on their cases midstream.

“There are often times where my own personal docket is about a third to a half transfer cases from my colleagues that I have to take on and make sure they have as seamless of representation as they can,” she told City Limits.

“We are not able to take on new cases and [have] to just advise tenants on how to represent themselves because we are absorbing cases from other people,” she added.

According to a tracker maintained by the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition, as of Feb. 1, 58 percent of tenants sued for eviction since mid-January 2022, who have appeared at least twice in court, hadn’t been assigned lawyers. The tool does not account for tenant income, so some tenants in this count may not qualify for free counsel.

Adi Talwar

Center: Tara Joy, a housing intake specialist at Mobilization for Justice, leading the chants while picketing with her colleagues outside MFJ’s Manhattan office. “My colleagues are drowning in just the sheer volume of intakes that they have to do,” Joy said.Tara Joy is a housing intake specialist at MFJ, on the paralegal pay scale. She coordinates the intake process, and visits Bronx Housing Court each week, where her colleagues inevitably have to turn away some share of the tenants who qualify for Right to Counsel. This work is both time consuming and disheartening, she said.

“I can see that frankly my colleagues are drowning in just the sheer volume of intakes that they have to do,” Joy said.

On Wednesday night, the New York City Office of Civil Justice hosted its annual hearing soliciting feedback on Right to Counsel. MFJ submitted 28 pages of joint testimony alongside Legal Aid, Legal Services NYC and others, describing an attrition problem they said is industry-wide.

“The most direct way to mitigate the risk of attrition for the citywide program is to fund it sufficiently,” the organizations wrote. This would allow them to hire enough staff to ensure “manageable caseloads for attorneys with varying levels of housing experience.”

MFJ management and its peers understand what legal workers are up against in housing court, said Brian Sullivan, a senior staff attorney in MFJ’s housing practice who attended Tuesday’s picket. But workers have a tool that their bosses lack, in the strike.

“As employees of a nonprofit that’s funded primarily by the city and state… we’re also, in an indirect way, negotiating with our funders,” he said. “And when we get better wages, our bosses are positioned to tell the funders, ‘We need to meet this.’”

Even the most compelling argument for increased funding can ultimately be disregarded, according to Sullivan, whereas a strike is harder to ignore. In a largely-unionized sector, there is a lot of potential for leverage.

“Whoever is funding this work, is serious about this getting done, you need the unionized workforce to accomplish that,” he said. “By withholding our labor, we force the issue.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Emma@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org