Photo by: Pearl Gabel

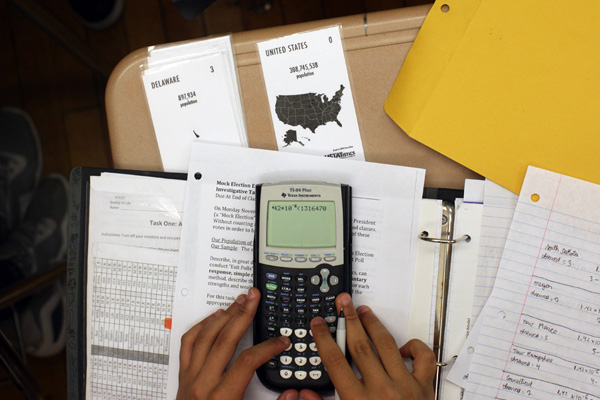

A student in Eleanor Terry’s Advanced Placement Statistics class at the High School of Telecommunications, Arts and Technology, where campaign 2012 is a lesson in math and citizenship.

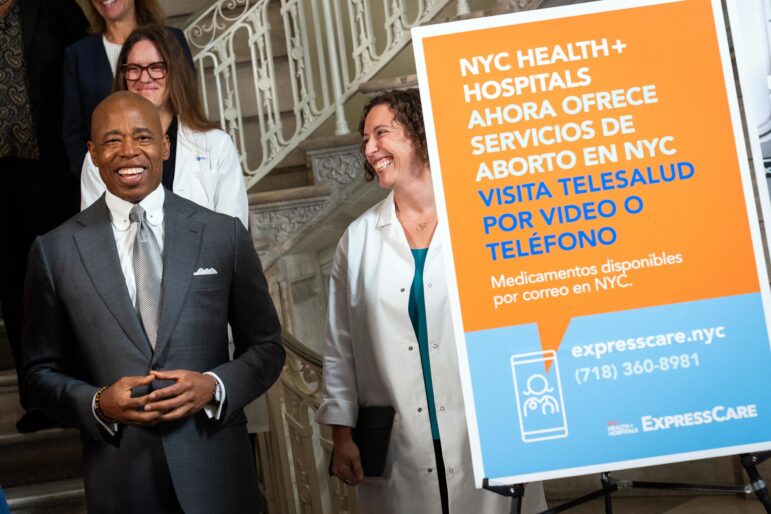

Students file into a third floor room for their 10:30 a.m. lesson; there is not an empty chair among the 32 students in the Advanced Placement Statistics class. They begin to work in groups, filling out worksheets about positive residuals and slopes while their teacher Eleanor Terry walks around the room.

Terry is leading them through a graded exercise using actual presidential campaign data to see if they can determine how political campaigns might use the Electoral College to their advantage, getting votes from states that are valuable because of their size, instead of just focusing on the popular vote. They hold cards that each show one state, its population and number of Electoral College votes. They sort them like playing cards.

“I’m sure there are people on these campaigns doing this kind of math,” Terry says loudly, pushing students to continue the exercise as they punch numbers into their graphing calculators.

These students are not just looking at past voting results or other people’s election polls. They will be designing their own independent election research. The culminating event for students will be conducting exit polls of voters on Election Day, November 6, outside polling places in their Brooklyn districts.

Research on swing states

Terry, a math teacher for eight years, made the presidential election the focus of research supported by a Fund for Teachers professional development grant. She spent the summer developing in-depth research on election campaigns and polling to incorporate into her statistics class.

She wanted to develop curriculum that engaged students in civic participation in a way that would carry through to their adulthood, and that also strengthened critical thinking skills. Statistics are an ideal tool for developing those traits because it allows students to dig deep into problems and display their knowledge through both problem solving and essay writing, “You get to see this new window into their brains,” she says.

More importantly, she saw her students, many from immigrant households, reflecting an underrepresented population among voters but also an untapped and potentially powerful group in U.S. politics.

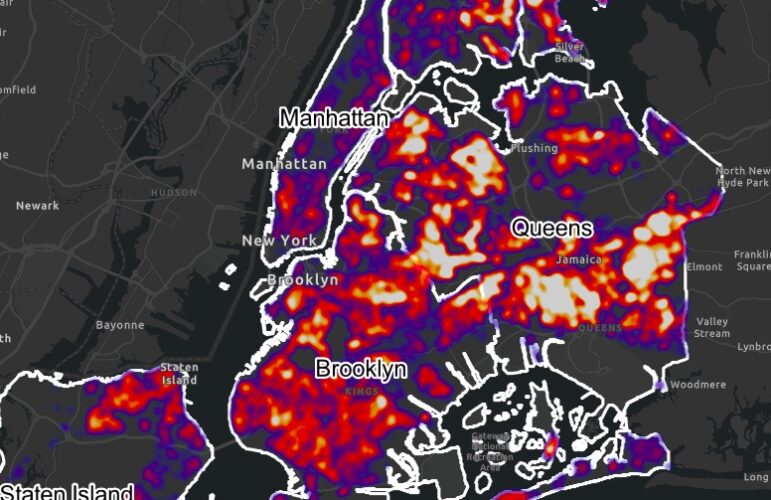

Terry’s students reflect the diversity of the High School of Telecommunications, Arts and Technology, which sits on the border of Brooklyn’s Sunset Park and Bay Ridge neighborhoods. More than half the student body is Latino, with a smaller percentage of white, Asian and black students also represented.

Latinos are America’s largest minority group according to a Pew Hispanic Center analysis, and the number of eligible Latino voters has increased by 20 percent over the past four years. However, Latino voter turnout rate is far lower than that of whites or blacks.

Terry wanted to look at how political campaigns were engaging with the growing Latino population; she worked with polling statisticians and Get Out the Vote efforts in the swing states of Florida, Colorado and New Mexico, conducting her own surveys outside big box retail centers like Target and Wal-Mart.

Ali A. Valenzuela, a Princeton assistant professor at who studies Latino politics, public opinion and voter turnout and elections, sees Terry’s research and interactive lessons as a way to connect with young people, particularly underrepresented groups such as Latinos, by engaging in their own communities.

“There is this nasty cycle that is going on in terms of the way in which our campaigns are being run,” Valenzuela says, pointing out that political parties often opt for television advertisements over door-to-door, personal outreach, often leaving already marginalized groups out of the campaign message. This leads to those groups participating less.

Debates to the Daily Show

Midway into the semester, the same group of students Terry once worried were disengaged from current events rattle off election analysis with ease and confidence. In a discussion of what they’ve learned so far in the class, Salvatore Polizzi, 17, says part of their homework is watching the debates. He decided, after watching the one of the debates that he didn’t like how Vice President Joe Biden was interrupting the Republican vice-presidential candidate, Rep. Paul Ryan.

Aileen Gonzalez, also 17, jumps in to disagree, “I don’t think so,” she says. “I think [Biden] loves politics. He’s in it to win.” She adds, “He was kind of overcompensating for [President] Obama’s lack of aggression” in the first debate.

The students may watch the debates on television, but most of their time is spent online, getting news and opinions via Facebook and other social media sites. They like the Daily Show, and the Colbert Report but also mention interest in more serious news outlets like the New York Times.

Their teacher adapted her lessons to connect with students through social media; student assignments and lectures are often done online. She posts her research as well as theirs on her class blog. For homework, students often must comment on the blog, listing statistics used in a recent debate or responding to posts of articles, video and commentary about the upcoming election, polling and campaign trends.

“Service learning, doing these kind of projects in conjunction with a class as opposed to just volunteering leads to the greatest civil knowledge,” says Terri Epstein, the Coordinator of the Adolescent Social Studies Education Program at Hunter College, citing research in a recent Carnegie Corporation’s report that concluded that students who participate in civic activities in high school stay engaged for as many as 10 years after high school.

Valenzuela’s own election research finds that personal contact is the strongest way to connect with voters and increase turnout, and for students to do direct research engaging with voters combines learning with outreach. It becomes, he says, “one of the best ways to take a topic like statistics and polling and give them actual meaning in people’s lives.”

What matters to them?

In class, Terry has emphasized topics that resonate with her students. Since many are the children of immigrants or immigrants themselves, “the DREAM Act is at the forefront of their minds.”

When asked about campaign issues that matter to them, students list immigration, unemployment and other economic issues. Many have undocumented friends going through the college application process, where a lack of papers affects financial aid eligibility. One student’s older sister who recently graduated college can’t find a job. Others note that because of President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, young people can stay on their parent’s health insurance until they are 26 years old.

Gonzalez admits that before, if her family received a polling call, she would hang up. Now she is familiar with how questions are framed, whom they target, and how they work, so she sees it differently. “We talk about the survey strategies. Ways to be biased, ways not to be biased,” she says. “Polling makes more sense now.”

Luis Beato, another senior, goes back and forth between being serious and detached about politics. He isn’t sure if he would vote if he were 18. He was critical of people who are uninformed and blindly follow one candidate or another. “Before this I really didn’t care about the debates or anything like that,” Beato says. “Now I’m intrigued on what’s going on. I want to see if those facts or numbers are true.”

Having Terry’s summer doing door-to-door, person-to person voter outreach in swing states as an example seems to have given the students confidence that they too can approach people and conduct their own surveys. Jacky Lee, one of the few juniors in the class, voices his enthusiasm for the project. “In my opinion, we are all getting experience how polling and voting works,” he said, “Its fun for us, taking stats in to the real life world, into our future.”