The Department of Housing Preservation and Development's Draft East Harlem Housing Plan

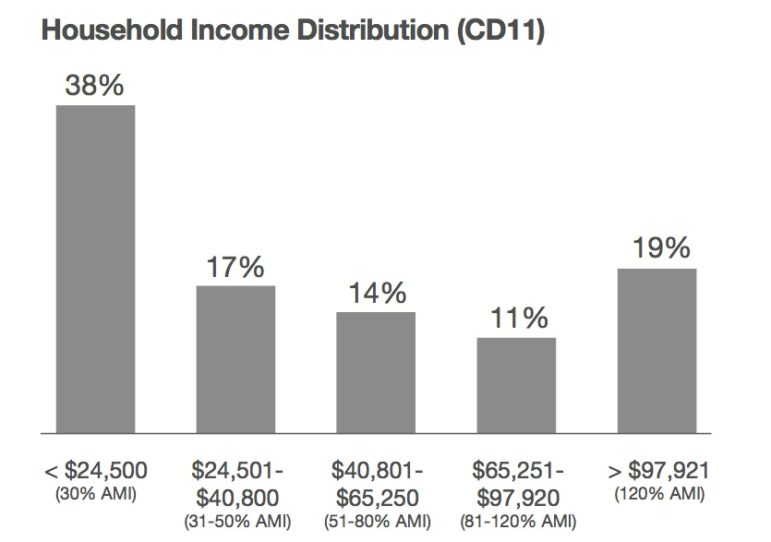

Household income distribution in East Harlem's Community Board 11

As City Limits reported on Wednesday, there are East Harlemites who oppose a rezoning of any sort and have their own plans to stem gentrification, and others who would accept a rezoning if it follows the recommendations of the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan, a proposal created by a steering committee formed by Speaker of City Council Melissa Mark-Viverito and outlining a rezoning along with a wide range of other policies.

For residents of the first group, the Monday release of the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development (HPD)’s draft housing plan for the neighborhood was something of a non-event: No HPD investments and initiatives, they argue, will be able to make up for the displacement that will accompany the city’s proposed rezoning.

For the more optimistic group, however, the released plan provides a barometer of how much the city is following the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan’s recommendations—and whether it can do enough to protect residents from the potential displacement that a rezoning and market forces could cause.

“We can expect all sorts of negative pressures, so this HPD housing plan to me is supposed to counter that…so that we can make an informed decision,” says Dennis Osorio of Community Voices Heard.

While these participants recognize HPD has adopted some of the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan’s recommendations, many wish the plan was more specific and are concerned it might not do enough to protect the most vulnerable from displacement.

HPD plan still in process

In several neighborhoods targeted for a rezoning by the Department of City Planning, HPD and other agencies are offering neighborhood investments to accompany a potential rezoning. These investments, while they tend to shape the course of the discussion on a rezoning, are not legally binding and not part of the rezoning that must be approved through a public review process.

The de Blasio administration has signed legislation requiring it to clearly publish agencies’ commitments online in order to improve transparency, but some advocates think the administration could go further to improve accountability. It’s also not clear what investments HPD would make in the neighborhood if City Council does not approve the East Harlem rezoning.

HPD’s draft plan released Monday includes a mix of ongoing, older initiatives and relatively newer ones. The agency will continue its citywide outreach to property owners to bring more buildings into affordability agreements and renew existing regulatory agreements, but is also focusing special attention on East Harlem and other neighborhoods targeted for a rezoning, including by piloting a “Landlord Ambassadors program,” which will use community organizations to conduct additional outreach to property owners.

The plan says it will continue enforcing the housing maintenance code, but says it is making an additional effort in East Harlem, Inwood, and Jerome Avenue (all neighborhoods that the administration has proposed rezoning), including through “block sweeps” where HPD looks at all buildings on the same block as a distressed property.

The plan highlights the mayor’s recent commitment to a right to counsel for all low-income tenants in housing court, the city’s ongoing work to prosecute bad landlords, and educational initiatives to inform tenants about their rights. The plan notes that funding is available to community organizations for tenant organizing, though there is as-of-yet no extra funding set aside for East Harlem groups.

As for new construction, HPD says the proposed rezoning will ensure that 20 to 30 percent of the new units that a rezoning could generate would be rent-restricted under the city’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy. Such buildings would be allowed to make use of the recently renewed 421-a subsidy. According to a City Limits analysis of the city’s Environmental Impact Statement, with a rezoning developers would build 1200 and 1800 more units of rent restricted housing—as well as between about 4200 to 4800 units of market-rate housing (though some stakeholders say the city is underestimating both numbers).

In addition, HPD has promised to fund 2,400 units of rent-restricted housing on public land, with some projects including 20 percent of units for households at 30 percent Area Median Income (families of three making below $25,770) and that the city is working on a new termsheet to provide even deeper affordability. Agency officials also justify building for a mix of income levels up to 130 percent AMI or $111,670 for a family of three, emphasizing that rent burdening occurs across all the neighborhood’s income levels (though census data shows the poorer you are, the more likely you are to be rent-burdened).

The plan notes that the city is willing to sponsor even more affordable housing if private developers are interested—though that possibility becomes less likely as the neighborhood becomes attractive to market-rate developers. It also cites four programs to either help non-profit developers get funding or connect with other mission-driven groups that wish to develop their underutilized land.

The city is making it easier to learn about and apply for rent-restricted housing and has instituted a new rule preventing applicants from being rejected just based on credit score or on their involvement in Housing Court cases (except those involving “serious circumstance” like “for-cause eviction and judgment of possession”).

On the economic development front, the agency is now requiring that all developer applications for building on city-owned land include a local hiring plan, and that HPD projects receiving $2 million or more in subsidy ensure a quarter of their HPD-funded costs are spent on Minority and Women Owned Businesses.

The agency also holds out some hope for the community land trust model, saying it is in the process of “evaluat[ing] submissions to identify non-profit organizations with capacity to create and operating CLTs.” It also notes that a city working group is exploring the feasibility of a citywide certificate of no harassment program, and results will be released soon.

Furthermore, the agency says its plan is just a draft that will continue to be revised throughout the seven-month public review process known as ULURP, that it is still in the process of exploring other public sites in the neighborhood for development, and is seeking input from neighborhood groups to develop a coordinated preservation strategy for the neighborhood.

Concerns about transparency and content

Last Thursday, a few days before the plan was publicly released, the city sent a 35-page powerpoint presentation on the plan to the members of the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan steering committee’s subcommittee on housing preservation, which City Limits obtained through a source. The subcommittee included many members of the steering committee that approved the Neighborhood Plan, as well as a few community members who are not on the steering committee and are more critical of the rezoning that the steering committee proposed.

The city presented its powerpoint at a closed-door meeting of the subcommittee on Friday. Some rezoning opponents said the city was not being transparent by showing its powerpoint to a favored few first and failing to make it available online (the powerpoint is still not available online, though it’s similar to the plan that is now public). But these opponents’ objections also concerned the substance of the plan.

“There is nothing HPD can do to alleviate the massive displacement that rezoning will cause. Tenants are already under attack from unscrupulous landlords. Meanwhile, the city can’t track—let alone adequately manage—complaints, track (and protect) regulated units, or provide funding and other support for families in need of permanent affordable housing,” said Marina Ortiz of East Harlem Preservation via email, while meanwhile El Barrio Unite’s Roger Hernandez asked, “Why do we need to read HPD’s [35]-page rezoning nonsense that only serves to displace NYC’s poor with a publicly financed Mayor’s proposal which will gentrify our community?”

HPD’s plan does not address the concerns of Movement for Justice in El Barrio, a group of immigrants in rent-stabilized housing in the community, that HPD’s code enforcement process needs to be revamped as outlined in the group’s 10-point plan. The group, which says it needs more time to analyze HPD’s plan, is also wary that HPD’s tenant educations strategy may be ineffective.

Those on the subcommittee who did get that early glimpse of the plan on Friday did not let HPD off the hook.

Some said that HPD’s initiatives deserved praise—with one participant even saying the others should be more appreciative—but most expressed concerned that the plan didn’t respond with more specificity to the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan’s recommendations, and called for more thorough analysis of the plan’s potential effects on displacement.

Regarding those promised 2,400 units, there were requests for more specificity about the proposed rent levels, with some saying that affordable housing for households at 130 percent AMI, or families of three making $111,760, cannot be considered affordable. (Other participants in the room defended the need for such units. It’s worth noting that the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan also defined affordable housing up to 130 percent AMI.) There is also continued concern that the city has not committed to 100 percent rent-restricted housing on all public land.

Christopher Cirillo, executive director of Lott Community Development Corporation, pointed out that among the 2,400 units that the city says it will construct in conjunction with the plan, 750 are on a site that has been in the HPD pipeline since well before the de Blasio administration took office (and, one should note, another two sites with about 600 units together are projects that have already been approved by City Council).

In an e-mail to City Limits after the meeting, Cirillo also expressed concerns with the limitations of the city’s plan to include non-profit developers. As City Limits reported last month, nonprofit developers feel the de Blasio administration has strengthened a reliance on the for-profit sector.

“Regarding the EHNP’s strong recommendations about substantively involving locally-based non-profits and CDCs, HPD’s draft plan is completely inadequate,” Cirillo added in an e-mail. “It touts a handful of existing programs and a few new initiatives targeted mainly to mission-driven property owners (e.g. churches), but it makes no real mention of supporting non-profit affordable housing providers and CDCs in new development or preservation. The recent example of selecting an exclusively for-profit development team for the East 111th Street RFP site has heightened concerns about whether HPD will follow through on the EHNP’s recommendations related to non-profit/CDC developers.”

Others at the meeting wanted more information about the potential loss of existing affordable units, with some asking HPD to determine which rent-stabilized units were in jeopardy of deregulation and which building regulatory agreements were nearing expiration. The Urban Justice Center’s Pilar DeJesus told City Limits she is especially concerned of the threat to tenants due to the Rent Guidelines Board’ preliminary vote to permit a rent hike, and she wants strategies for preserving NYCHA housing to be included in the plan. (A separate group, the NYCHA subcommittee, plans to follow up with NYCHA but is somewhat behind.)

Marie Winfield, director of the East Harlem Community Land Trust and a community board member, noted at the meeting that the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan participants had worked to take a count of how many units of affordable housing would be lost through deregulation over time and how many units would be created that would accommodate such populations, and wanted to see HPD make a similar comparison.

It’s important to note, however, that neither plan takes into account the potential for the loss of affordable units to speed up due to a rezoning.

Winfield also asked HPD to explore the complex issues surrounding the federal fair housing mandate. She wants to ensure the residents most vulnerable to displacement have access to the new below-market units, but notes that the city’s neighborhood preference policy—which allows residents of a local community board to receive preference for 50 percent of a development’s new affordable units—is at risk of being ruled unconstitutional under the Fair Housing Act for purportedly furthering segregation. She is also concerned about the potential for landlord discrimination as the neighborhood continues to gentrify.

Diane Collier, chair of community board 11, commended HPD’s local hiring strategy, but also made some suggestions to improve the affordable housing lottery and hiring process, as well as told HPD “everything else they’re asking for, you really should pay attention to,” in reference to critical voices in the room.

Osorio of Community Voices Heard voices concerns that public review for the rezoning is beginning with only a draft version of HPD’s plan, and that the community board will have to vote on the proposed rezoning without knowledge of HPD’s final plans. Given that East Harlem has been talking about a certificate of no harassment and community land trusts for years, it was not enough for HPD to vaguely promise continued exploration of those two solutions, he says.

HPD appeared to take into account some of the feedback it received on Friday—at least to make changes to wording before making its plan public on Monday. It caveated that some of the 2,400 units were long in the pipeline, added a section on developers’ responsibilities to build fair housing, and created a new section on supporting small businesses and meeting local retail needs.

The Community Board 11 task force will hold a meeting to discuss the city’s proposed rezoning of East Harlem on Thursday May 4, 6:00 pm, at the Bonifacio Senior Center at 7 E 116th Street. HPD will present its neighborhood plan, while George Sarkissian from the Speaker’s office will present the priorities of the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan Steering Committee members.

On May 16 at 6:30 pm, the board will host a hearing on the rezoning and the 111th Street ballfields project at the Siberman School of Social Work at Hunter College, 2180 3rd Avenue.